January 15, 2021

COVID-19 has impacted every aspect of K–12 education, from familiar classroom routines to when and how we assess our students. With thousands of buildings closed and millions of students learning remotely, educational data is playing a more important role than ever this year—which makes it all the more critical for every school and district to have an effective culture of data use.

This raises an obvious question for district and building administrators: What does a successful data culture look like in the era of COVID-19? What proven strategies can you use to engage stakeholders and ensure that every student receives the just-right level of support, no matter the learning environment?

We recently discussed these questions with Abigail Cohen, Associate Director for Policy & Research at the Data Quality Campaign, a nonprofit organization that’s the nation’s leading voice on education data use and policy. Following are four key takeaways from our conversation, along with links to helpful resources.

#1. Focus on the fundamentals

As we noted in a recent blog, people often respond to uncertainty in one of two ways. Some seek a truly novel solution, something that’s never been done before. Others take the opposite approach, going back to the basics and doubling-down on the fundamentals. This is often the better choice.

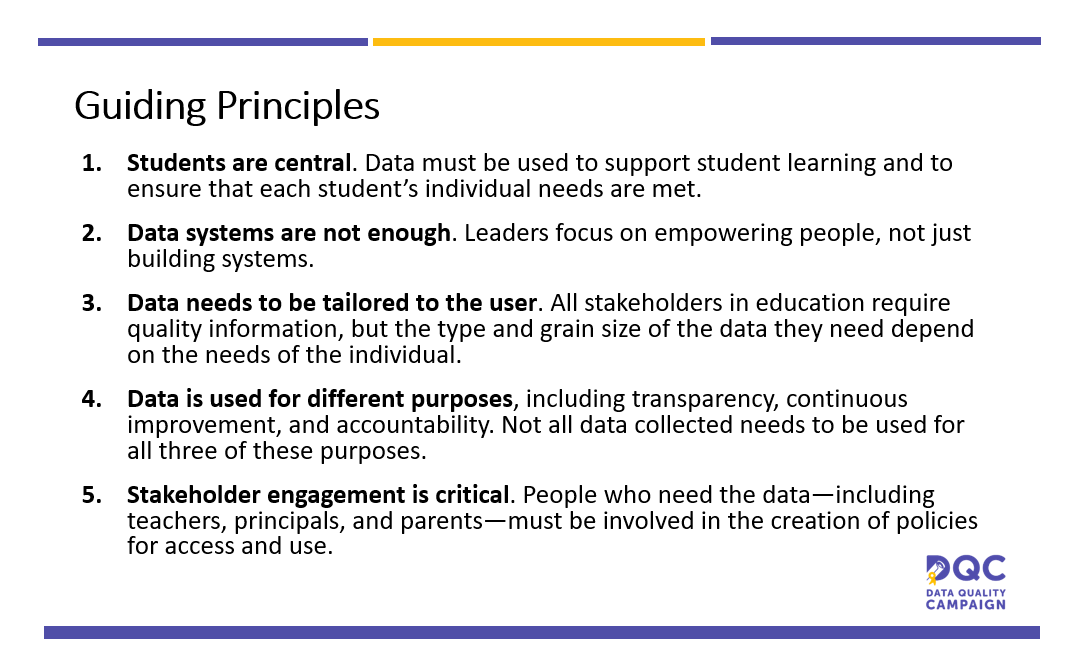

Given the COVID-19 disruptions, focusing on the fundamentals—what the Data Quality Campaign calls the Guiding Principles of Effective Data Use—is key. So, what does this involve? Educators obviously collect a lot of data about their students: attendance, behavior, assessment scores, course grades, classroom observations, and more. But our goal as educators isn’t to amass data but rather to help students succeed. Students must be central to everything we do. If we’re collecting data that doesn’t contribute to this goal, or if we’re not actively using our data to form a more complete picture of students’ strengths and needs, then we need to reexamine what we’re doing.

Going along with this is the idea that data systems are not enough. As Cohen explains in the webinar, at its founding, the Data Quality Campaign focused on systems-building, helping states develop their longitudinal data systems. Too often, however, these systems didn’t live up to their potential—not because they were necessarily flawed, but because the data wasn’t readily available to those who needed it. Even when data was available, end-users often didn’t have the time or resources to draw actionable insights from it. This led to a shift in the Campaign’s work, from a focus on effective data systems to a focus on effective data culture.

This brings us to the third principle—that data must be tailored to each user’s specific needs. Not only do different stakeholders (administrators, teachers, parents, students, community members) need different types of data, but it’s important to recognize that not every piece of data will be actionable to every stakeholder. To give but one example: both superintendents and teachers need to understand the impact of the “COVID Slide” on student learning. Clearly, superintendents need a broad, district-wide view, so they can make decisions about service delivery and resource allocation. Teachers, however, need a very granular view—down to discrete skills—of what their students have mastered, what they’re ready to learn next, and where critical gaps exist.

While both superintendents and teachers get this data from the same source (e.g., students’ performance on interim assessments), their needs are very different in terms of the grain size, the questions they need to answer, and the next steps they will take.

#2. “Data is not a hammer”

For some educators, the term “data” is synonymous with “accountability”—as if data is only useful for finding gaps and problems. It’s true that data plays an important role in helping to identify unmet student needs and inequitable allocation of resources. There are also times when administrators need to have tough conversations, based on what they’re seeing. But, as the Campaign’s fourth principle emphasizes, data is used for different purposes: not just for accountability, but also to highlight what’s working, to increase transparency, and to support continuous improvement within and across schools.

Critical to this is the final principle, that stakeholder engagement is vital. As Cohen notes, this is often the biggest barrier to an effective data culture. So, what can administrators do? One of our Renaissance colleagues—a former district administrator—likes to use the phrase “inspect what you expect”, which is very relevant here. In short, administers first need to ensure that teachers and support staff:

Have the time and expertise to review student data, and to plan instructional next steps based on what the data shows;

Have a voice in the process of data collection and use, and are empowered to ask questions and provide feedback about these processes;

Understand that data—in Cohen’s words—is not a hammer, used solely for accountability, but a flashlight, showing what’s working and where to focus our efforts for improvement;

Understand that data use is an ongoing process throughout the school day, not something that only happens during data-team meetings.

Once administrators have made clear what they expect—and have ensured that teachers and staff have professional development around effective data use—they then need to inspect. This includes regularly visiting school buildings (when possible), sitting in on data-team and PLC meetings, and gathering ongoing feedback about successes and challenges. Actively participating in the process goes a long way toward engaging stakeholders—and supports the shift from a culture that only views data through the lens of accountability to a culture that proactively uses data to improve teaching and learning.

#3. Data is an ongoing, collaborative process

One of the Data Quality Campaign’s most popular resources is an infographic called Mr. Maya’s Data-Rich Year. This graphic shows a principal’s journey over the course of the year, as he interacts with teachers, staff, students, and parents; develops a strategic plan and goals; tracks progress and growth; and works to continually improve the delivery of services to his students.

This journey will look somewhat different in the era of COVID-19, with Zoom calls replacing in-person meetings, and with data from interim assessments helping to fill the gap left by the cancellation of state testing last spring. But, as Cohen explains in the webinar, the key points remain the same:

Data isn’t just one person’s or one team’s responsibility. Instead, everyone is involved in using data to make decisions and monitor students’ progress—whether this is progress in a particular academic course or progress toward important long-term goals (graduation, etc.)

Data use should be embedded in day-to-day activities. Data use can’t be limited to weekly team meetings. Instead, data should inform teachers’ daily decisions about what to teach next and how to group students, and administrators’ decisions about what to invest in and where to direct resources.

Data use is collaborative—and teachers need support to do it. Administrators should model effective data use, have authentic conversations with teachers and staff about data, and provide tools and resources to support data literacy.

The Campaign has also created a companion infographic, showing the data journey from the teacher’s point of view. Again, the key steps in this process—reviewing formative and interim data, setting goals, collaborating with colleagues, and tracking student progress—remain the same this year, even if most of the interaction occurs virtually.

#4. Look beyond the COVID-19 disruptions

There’s no denying that COVID-19 creates challenges for data collection and use. For example, observing students in the classroom is difficult when students are not physically present in the classroom. As Cohen points out, the pandemic also requires us to rethink familiar definitions. For example, what does “chronically absent” mean in an era when many students are learning asynchronously, accessing different platforms and apps from home?

Educators have made major efforts to ensure that learning continues despite the disruptions. With so much focus on meeting students’ immediate needs, it can be difficult to look toward the future. But Cohen suggests that administrators consider the data they can collect now that will be useful in the future, as they seek to fully understand the impact of COVID-19 on their students’ performance and growth.

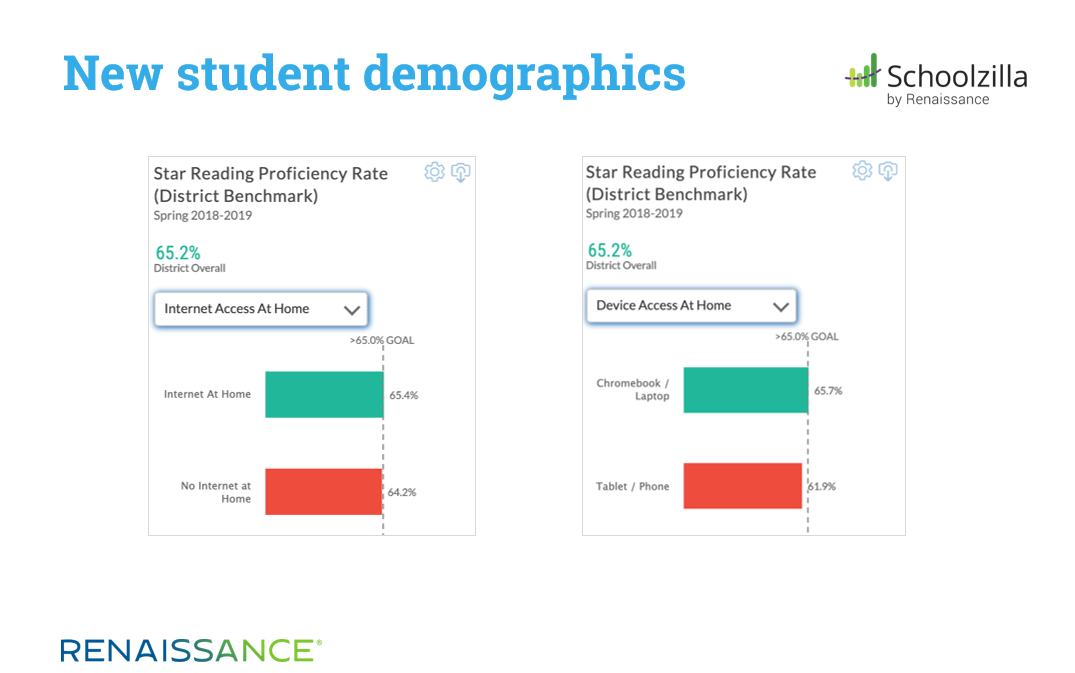

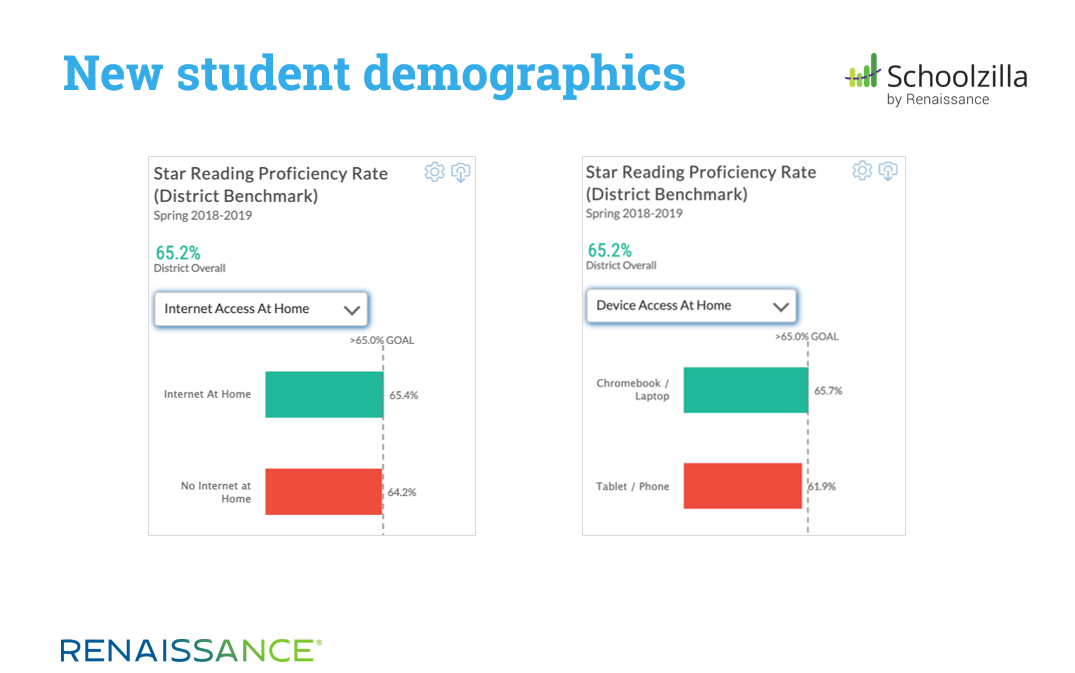

The pandemic has also shown the need to collect new demographics. In the past, tracking students’ level of at-home connectivity and device access wasn’t necessarily “mission critical” in most districts. Now, this information is indispensable for ensuring that students have access to online learning opportunities, and for understanding how access (and lack of access) is affecting performance. The following example shows data visualizations in Renaissance’s Schoolzilla platform, allowing administrators to disaggregate data from the Star Reading assessment using these two metrics.

How Renaissance supports effective data use

Understanding the features of an effective data culture is one thing; creating and maintaining such a culture is something else. At Renaissance, we offer a variety of remote and on-site professional services that focus on effective data use—including new offerings on remote testing, on using Focus Skills to address learning loss, and more. Please don’t hesitate to contact us to discuss professional learning options, or with questions about using Renaissance products to help ensure that learning continues, regardless of how you’re providing services to your students.

Learn more

Ready for more insights on creating a positive culture of data use this year? Connect with an expert to learn how Renaissance can help.