September 22, 2020

For many of us, fall screening may look a bit different this year, especially if we’re assessing students remotely. Nonetheless, we’ll soon have—or may already have—our fall screening results. Based on this data, we’ll need to make intervention placement decisions, and when we place students in formal interventions, we’re generally required to set a growth goal to help gauge whether the intervention has been effective.

Just about any way you look at it, goals are good. They motivate us. Setting a target and striving for it often unleashes previously untapped reserves of energy. For years, Bob Marzano has written and spoken about the value of having students set goals and track progress toward them. This nearly always pays dividends.

But, for teachers, wanting to have goals for their students is one thing, and feeling comfortable about actually setting those goals is quite another. Setting realistic goals for general classroom activities is perceived as daunting enough, but when it comes to official growth goals for interventions, things often become overwhelming. This is the type of goal setting I’ll focus on here, because knowing how to appropriately set this type of goal will be key to equitably providing services during this anything-but-normal school year.

Goal setting and equity

Response to Intervention (RTI) and Multi-tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) have been described as frameworks for resource allocation. In other words, based on the assessment data we collect during screening and progress monitoring, we make consequential decisions about how to allocate our limited resources—the time, materials, staff, and other means at our disposal. Inherent in this definition is the sense of scarcity. In most schools, the resources are expended before every need can be addressed. Our objective, then, must be to equitably do the greatest good for the greatest number of students.

What people don’t always consider is the critical role that fully informed growth goals play within these models. The goal is the fixed element—the reference point—to which everything else is compared. If the goal is appropriate, everything works. However, if the growth goal is not aggressive enough, then the student is not likely to make sufficient progress to close the previously identified gap—even if he or she exceeds the goal. Similarly, if the goal is unrealistically high, then quite acceptable growth and progress might be perceived as insufficient, resulting in unnecessary changes to the intervention that require even more resources.

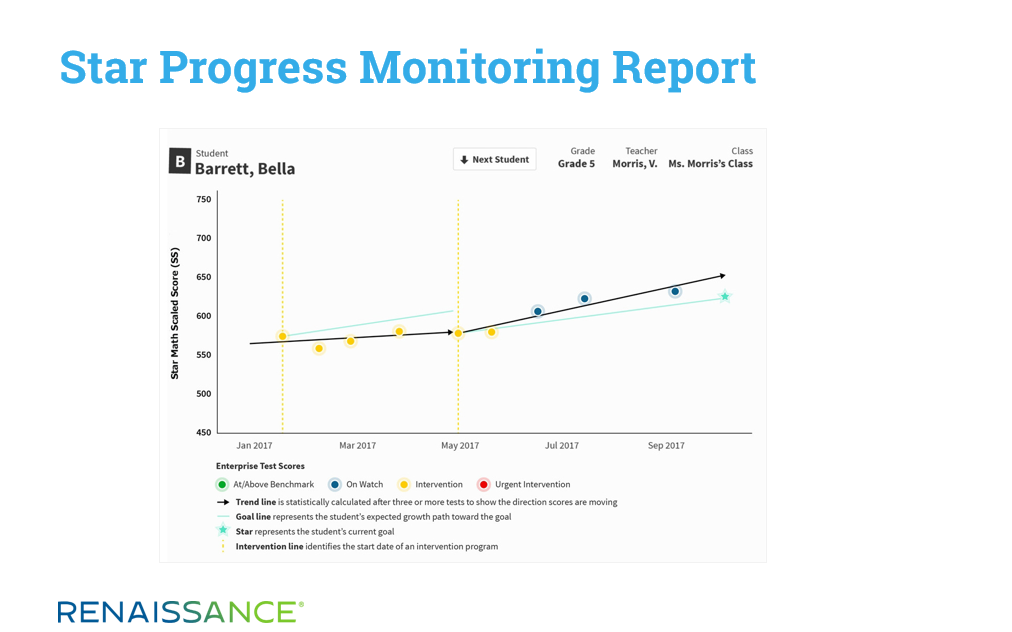

Within RTI and MTSS models, students’ progress (growth) is plotted against selected growth goals through the process of formal progress monitoring. This is generally depicted via a graph, as shown in the Progress Monitoring Report in Star Assessments:

Interpreting this information is a relatively simple matter of comparing the black trend line, which represents the student’s actual growth, to the green goal line, which represents the growth goal. In the example above, the black trend line (student performance) during the interventional that began in May exceeds the green goal line. This indicates that the intervention is working—the student is responding sufficiently. However, all of this is true if and only if the goal was appropriate in the first place.

For example, setting a less-than-ambitious goal for a third grader who’s reading at a Kindergarten level may grossly underestimate the growth this child could achieve. This may then lead to an underallocation of core and supplemental instruction and leave the child still lagging at the end of the year. By the same token, setting a goal to achieve end-of-third-grade expectations by the end of the current school year may be very difficult, if not impossible, for the student to achieve. This would create conditions of frustration and failure for both the student and teacher. These examples remind us that the consequential process of setting growth goals should be informed by as much context as possible.

The science of goal setting

Some educators take a straightforward but naïve approach to setting goals by simply saying, “I want to have this student be proficient by the end of the intervention.” Suppose that the desired level of performance is a scaled score of 700 on a given test, and that the student is currently scoring 550. That’s a gap of 150 points. If the intervention lasts for 10 weeks, some simply divide the gap in performance (150 points) by the number of weeks (10), and set a resulting goal of an increase in performance of 15 points per week. The problem is that this may or may not be realistic. Additional context is necessary.

Consider this second scenario:

- You have a student performing at a percentile rank (PR) of 11.

- Your overall benchmark (minimum level of desired performance) equates to a PR of 40.

- Meeting this benchmark by the designated end of the intervention would require growing at a rate of 7.0 scaled score points per week.

- When considering the grade level and starting point of this student, we see that growing by 5.5 scaled score points per week is a rate of growth achieved by the top 25 percent of students in the same grade who are beginning at the same point.

- If this student grows at a weekly rate of 5.5 scaled score points, she will finish the intervention at a PR of 30, which is 19 points higher than where she started.

Would growing at the same rate as the top 25 percent of similarly starting students and increasing your performance from a PR of 11 to a PR of 30 be considered adequately responding to an intervention? I think so. But if someone only considered the starting point (PR 11) and the ultimate destination (the PR 40 benchmark), then a growth goal of 7.0 scaled score points per week might have been set, and the growth that we just acknowledged as sufficient would be considered insufficient. As one of my colleagues remarked, focusing solely on meeting a performance goal “makes it seem like it’s not OK to celebrate growth unless a student is proficient. This is why so many students struggle: because people give up on them while they’re still trying to get there.”

When setting goals, we need to know more than the student’s current performance and the desired level of performance, which is often dictated by standards and accountability. This is why Renaissance has put so much work into the goal-setting capabilities embedded in Star.

Goal setting in Star Assessments

In a recent EdSurge article on goals, Kristen Huff writes that “the problem is that nearly all of the interim assessments used for setting student goals report only normative measures of growth, which compare a student’s progress to their peers, rather than how they are performing versus their grade-level expectations.” We are pleased that Star Assessments are an exception here because they provide multiple reference points—even more context—for setting goals.

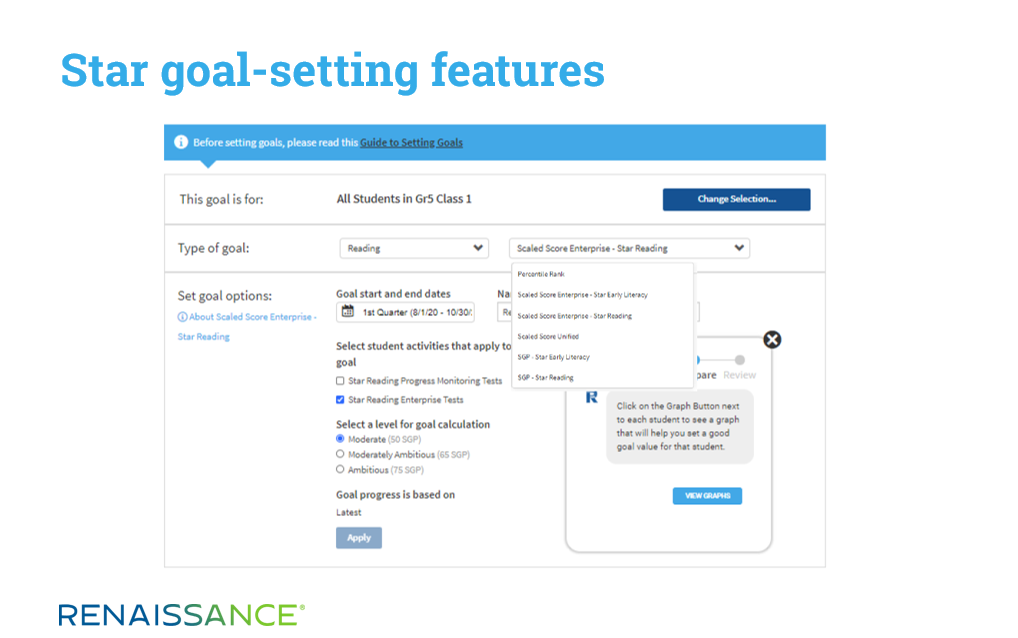

In Star, the goal-setting options include:

- Goals based on percentile ranks (e.g., “I want this student to finish the intervention performing at a PR 40 or above.”)

- Goals based on a particular scaled score that is linked to state performance levels (e.g., “I want this student to meet the state-prescribed level of proficiency by the end of the intervention.”)

- Goals based on Student Growth Percentiles (e.g., “I want this student to grow at a rate among the top 25 percent of her academic peers.”)

Having these options provides the greatest amount of context when settings goals. It also points out a deficiency in the goal-setting process of assessments with limited options, which offer less context. The ideal dynamic is to find that a goal of meeting proficiency expectations is viable within the time period of the intervention, but this is not always the case. When you find that a goal of meeting a desired benchmark (typically state-defined proficiency levels) during the course of a single intervention would require a rate of growth that few students ever achieve (e.g., an SGP of 95 or higher), you have to question the viability of such a goal. For some students, it simply may be that the time necessary to meet grade-level expectations while also achieving ambitious but reasonable growth may take more than one school year—an unpleasant reality, but one we need to accept if we truly want to help those students succeed.

Of course, the best alternative is to never let a child get so far behind that gaps can’t be closed in a reasonable period, but we know that too many students do fall appreciably behind before a formal intervention process begins. This forces a dynamic where we may sometimes need to address more sizeable gaps in performance through a perspective of “installments of growth” across several marking periods, semesters, or—in the most extreme cases—years.

We must always be striving for above-average growth with students who are behind. But while our goals should be aspirational, they must also be obtainable, or we are setting both teachers and students up for failure.

The art of goal setting

We should also note that setting goals is part science and part art. Beyond the obvious assessment information (e.g., the student’s current level of performance, desired level of performance, etc.), other factors must also be considered. What else do you know about the student? How much support does he have? How engaged is he—especially in a distance-learning environment? Are there other issues that are impacting academic progress, such as chronic attendance or discipline issues?

While much of this blog has focused on assessment information and associated goals, the fidelity of the interventions we provide must also be considered. If an intervention program is ill-structured or improperly implemented, nothing can be definitively determined about a student’s growth. RTI expert Amanda VanDerHeyden (2009) is famous for beginning data-team meetings with fidelity conversations before she ever reviews students’ results. She says that there is “such a strong relationship between failing interventions and poor implementation integrity that integrity ought to be the first hypothesis tested before an intervention is abandoned.”

She also notes that the challenge of monitoring the fidelity of multiple interventions occurring simultaneously across a school or district is becoming less daunting because of “rapidly emerging technology resources that can help ensure correct intervention use.” This includes “dashboard systems that organize student learning data and signal those responsible for implementation” with key metrics. Districts using Star Assessments may want to explore our Schoolzilla data visualization platform, which provides just this level of insight.

Goal setting in the year ahead

The truly critical issue in all of this is how best to accelerate learning for all students, and to differentially accelerate learning for those who are currently performing below expectations. The right question, from our perspective, is what mix of practices—including goal setting—will best contribute to that outcome this school year. The role of assessment is to reliably document what is occurring. When you have reliable assessments and the tools and context to set appropriate goals, you can make informed decisions about instruction and intervention—so you remain focused on what matters the most.

References

Huff, K. (2020). How ‘growth’ goals actually hold students back. Retrieved from: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2020-08-30-how-growth-goals-actually-hold-students-back

VanDerHeyden, A. (2009). Fidelity of implementation is key. Professional development resource created for Renaissance Learning.

Looking for more insights on the critical—and changing—role of assessments this school year? Watch the new webinar presented by Dr. Gene Kerns and Dr. Katie McClarty.