May 21, 2021

I love this quote from a recent EdSurge article on the importance of valuing teachers: “The phrase ‘learning loss’ has become as widespread as ‘you’re on mute’ in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.” As a former educator, I am in awe of the steadfast dedication that teachers, students, and families have applied to continued learning this school year, despite the many challenges. As a member of the Research & Design team at Renaissance, I am equally inspired by the student performance data that show the learning growth resulting from everyone’s dedication. I agree it’s time for the discussion to move away from “learning loss” and shift towards how to keep the growth momentum going.

In this blog, I’d like to dig into some of the findings from the new Winter Edition of How Kids Are Performing. The report compares the Fall 2020 and Winter 2020–2021 performance of 3.8 million students in grades 1–8 who completed a Star Early Literacy, Star Reading, and/or Star Math assessment in both time periods. I’ll focus specifically on (a) grade levels where we’re continuing to see some larger discrepancies between typical-year student performance and COVID-impacted performance, (b) some of the critical and potentially challenging skills that may be responsible, and (c) ideas for prioritizing instruction and classroom interaction time to accelerate student learning in these grades.

As context for identifying specific skills, I’ll draw on the work we’ve undertaken at Renaissance to create detailed reading and math learning progressions for every US state. Our learning progression developers—all of whom have educational backgrounds—first identify the skills inherent in each state’s reading and math standards. They then place the skills in a teachable order from kindergarten through high school, based on pedagogy, standards, and assessment data. An important component of this work is the identification of the most critical reading and math skills at every grade level, which we refer to as Renaissance Focus Skills. Focus Skills are embedded in our Star Assessments and are also freely available to educators on our website.

Understanding student performance in reading

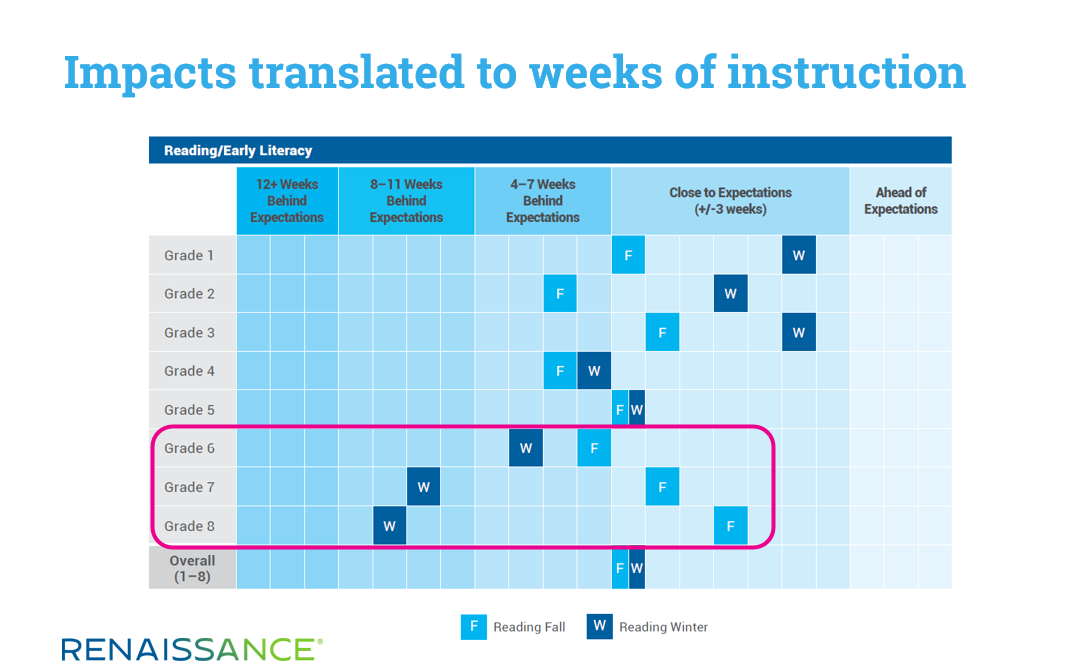

The following table from How Kids Are Performing translates the academic impact of COVID-19 into the number of weeks of reading instruction required to bring students in line with pre-pandemic expectations. (In other words, where we would expect students to be if the pandemic had not occurred.) The squares labeled “F” show the COVID-19 impact in Fall 2020. Those labeled “W” show the impact in Winter 2020–2021.

In grades 1–5, the data show that students made clear progress between fall and winter. In grades 6–8, however, the data indicate that students have fallen behind. After beginning the school year close to expectations, students in grade 6 were 4–7 weeks behind at the time of winter screening. Students in grades 7–8 were 8–11 weeks behind.

What might be responsible for this change?

Identifying challenging reading skills

The type of skills in grades 6, 7, and 8 that fall within the fall-to-winter instructional window require nuanced vocabulary, including shades of meaning like connotation, synonyms, and multiple-meaning words. They also require students to read for deeper understanding, such as identifying what an author thinks or feels and how the author wants the reader to feel.

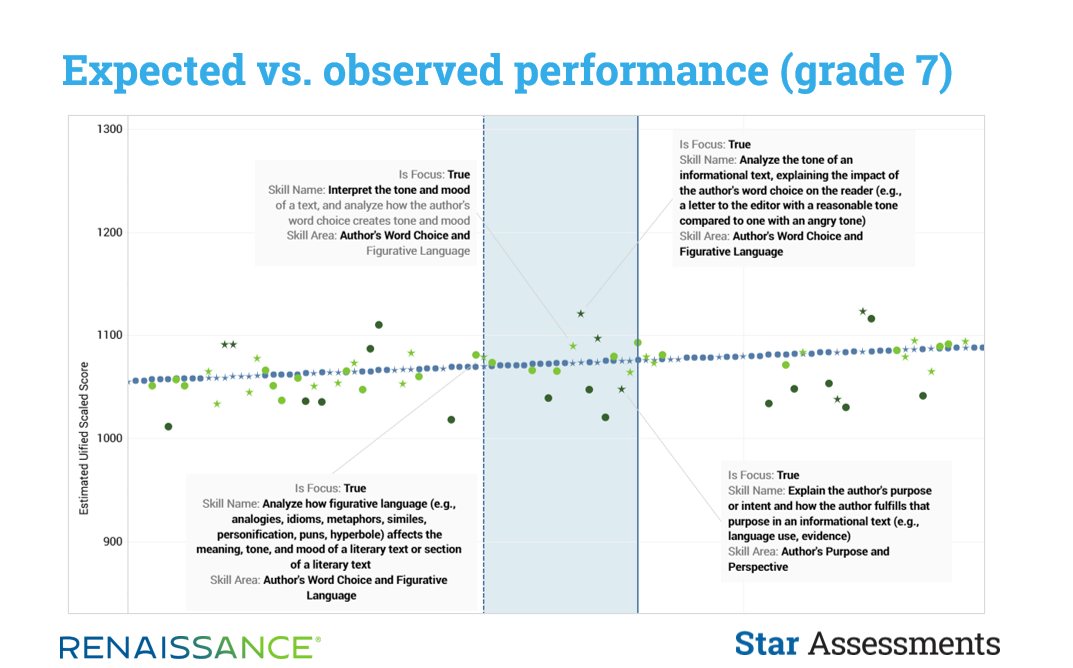

For example, consider the following graphic, which shows a segment of our learning progression for reading. The solid line on the right shows grade 7 students’ expected position on the learning progression in Winter 2020–2021. The dotted line on the left shows students’ observed (actual) position. The shaded blue area represents the distance between the two.

Within the shaded area, there are multiple Focus Skills, which are represented by the stars, along with non-Focus skills, which are represented by the dots. Each skill’s difficulty is expressed using the Star Unified Scale—the higher above the dotted blue line, the more challenging the skill.

In taking a deeper look at the shaded area, we encounter challenging Author’s Word Choice skills such as:

- Analyze how word choice creates tone/mood. This requires students to interpret the tone and mood of a text—and to analyze how the author’s word choice creates this tone and mood.

- Analyze characteristics of informational texts. This requires students to analyze and explain the characteristics and devices employed by different types of informational texts—including literary nonfiction (e.g., essay, biography) and argument—to begin to establish an interpretive framework for understanding different works.

Maximizing instructional impact on these skills

These grade 7 skills are reflective of key pillars of reading instruction at the middle-school level, as captured by a 2016 paper titled “Common themes in teaching reading for understanding.” The paper’s authors highlight the importance of active engagement with a variety of texts, classroom discussions, and building on students’ prior knowledge and vocabulary.

To make the best use of limited classroom interaction time—whether this is done face-to-face or using a platform such as Zoom—educators might consider:

- Prioritizing skills that benefit from discussion and interaction, such as those about the effect on audience, impact of word choice, or making inferences. As mentioned earlier, Focus Skills are a resource for identifying critical skills that should be prioritized.

- Combining similar skills during instruction. For example, at grade 6, our data identifies both Analyze characteristics of different forms of informational text, explaining structural differences and modes of discourse and Analyze characteristics of different forms of literary text, recognizing structural differences as challenging skills. Savvy text selection by the teacher might enable students to learn important text analysis skills in a way that transfers well between informational and literary texts.

- Ensuring that prerequisite skills are in place. For challenging skills like nuances of vocabulary and how word choice affects the reader, educators might revisit vocabulary from earlier grades, along with revisiting author’s purpose, because both will support students in going deeper on author’s word choice. This would also apply to cross-text analysis. Students are likely to struggle in comparing how two texts handle a theme if they don’t know how to identify a theme and how the author develops it in a single text.

Understanding student performance in math

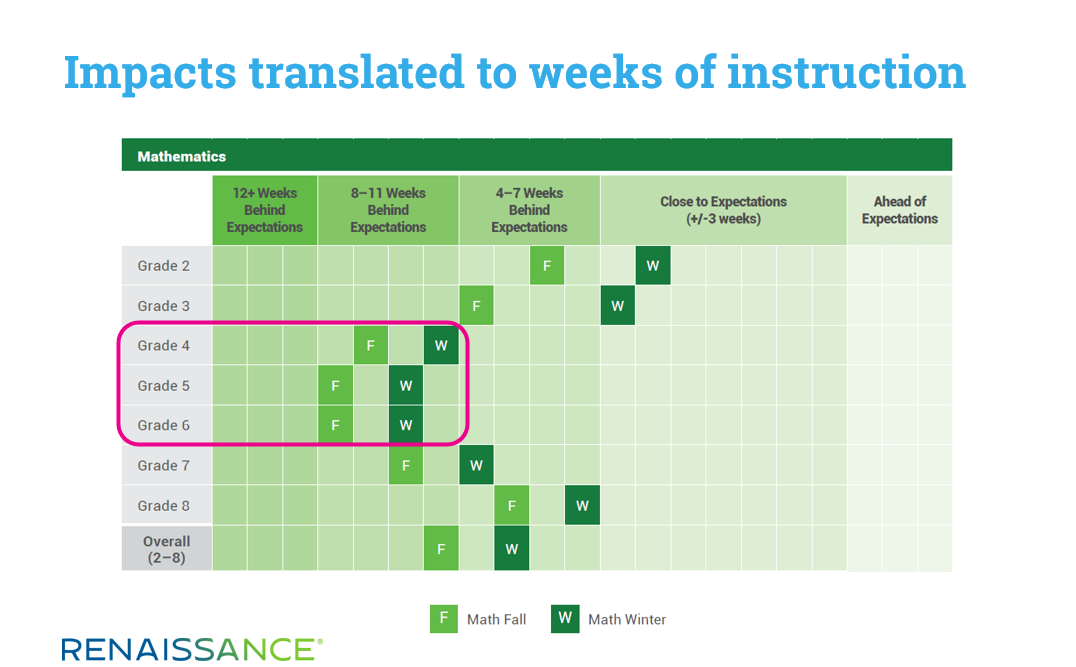

Like the table for reading we considered earlier, How Kids Are Performing translates the academic impact of COVID-19 into the number of weeks of math instruction required to meet pre-pandemic expectations. Again, the squares labeled “F” show the COVID-19 impact in Fall 2020, while those labeled “W” show the impact in Winter 2020–2021.

Here, we see that students at every grade level brought learning closer to expected performance in winter. The data for grades 4–6 show that even though student learning remains 8–11 weeks behind pre-pandemic expectations, students are clearly making up ground.

Identifying challenging math skills

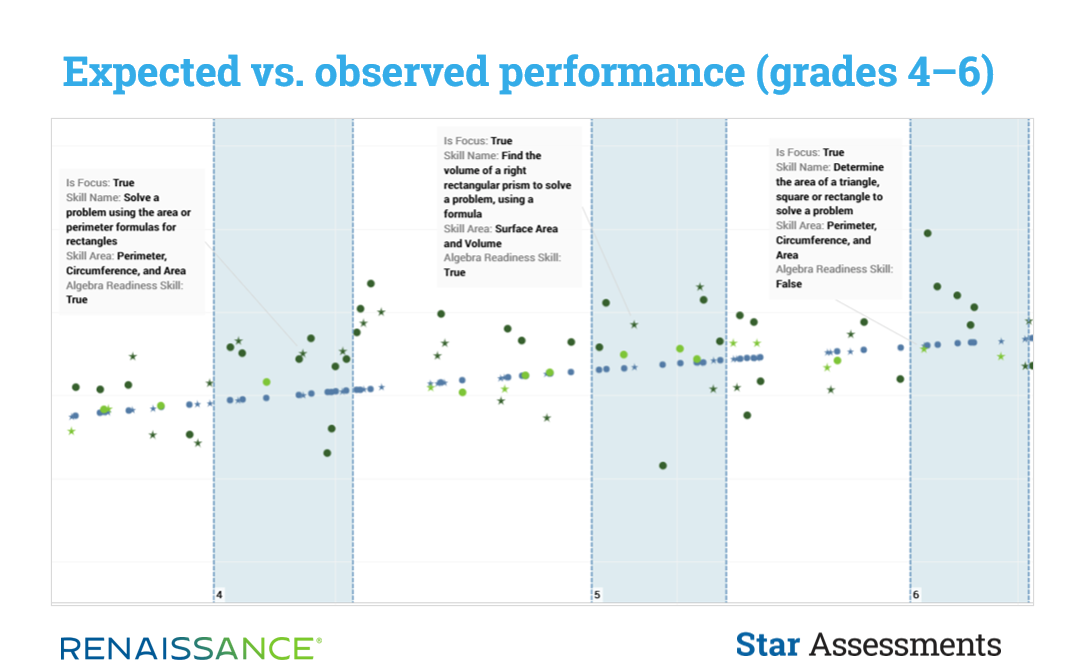

As in the earlier example for reading, the following graphic shows a segment of our learning progression for math. In this case, we’ve shown the difference between estimated and observed performance for students in three grade levels—4, 5, and 6—as represented by the blue shading.

The types of skills that fall within these instructional windows include challenging Geometry-based measurement skills that are also essential building blocks towards Algebra Readiness and problem-solving ability. The Focus Skills listed below highlight the importance of building a solid math foundation in middle school to support learning in subsequent grades:

- Grade 4: Solve a problem using the area or perimeter formulas for rectangles. This requires students to apply the concept of multiplication and knowledge of what perimeter and area mean to a real-world scenario.

- Grade 5: Find the volume of a right rectangular prism to solve a problem, using a formula. This requires students to continue to build understanding of three-dimensional shapes, to understand how volume differs from area, and to solve complex problems.

- Grade 6: Determine the area of a triangle, square, or rectangle to solve a problem. In this case, the student needs to determine which formula to apply in order to solve specific problems.

Maximizing instructional impact on these skills

The examples above also reflect the benchmark learning goals for these grade levels, as summarized in the National Math Advisory Panel’s “Foundations for success” document. Because achieving math milestones is critical for student motivation and future progress, and because of the many math skills that need to be covered at each grade level, educators might consider:

- Prioritizing challenging Algebra Readiness skills that that benefit from discussion and interaction, such as Divide mixed numbers or fractions. Students might grasp this concept more readily with visual modelling of separating everyday objects into parts (e.g., a pizza, a piece of paper, or sticks). Again, Focus Skills are a resource for identifying the critical skills to prioritize.

- Combining similar skills during instruction. For example, data skills like Use a line graph to represent data and Answer a question using information from a line graph could be incorporated into classroom discussions of the amount of time students spend on independent reading or math practice, with intentional sharing around the details of the structure and function of the graph.

- Ensuring that prerequisite skills are in place for application skills. For example, revisiting shapes, properties of shapes, and composing/decomposing shapes and ensuring students are proficient in their understanding of multiplication may also help new concepts of perimeter and area feel more accessible.

How persistence contributes to students’ success

In a recent blog, my colleague Dr. Gene Kerns pointed out that despite all of the challenges, many students are having a very legitimate school year. Although the phrase “persistence pays off” isn’t exactly original, I think this is a key takeaway from How Kids Are Performing. Educators have clearly found innovative ways to connect with students this year and to make full use of limited instructional time.

As I mentioned at the outset, it will be critical to maintain this positive momentum over the summer and throughout the 2021–2022 school year—not necessarily by doing new things, but by continuing to do things that you know are effective. And Focus Skills can continue to play an important role here, helping you to prioritize instruction to best support your students’ needs.

If you haven’t already, explore the reading and math Focus Skills for your state. Also, download the new Winter Edition of How Kids Are Performing for more insights on students’ progress and growth this school year.