March 19, 2021

March 2021 marks the one-year anniversary of the COVID-19 school closures. Do you remember our naivete as this all began? We were thinking in terms of weeks rather than months, and we thought buildings might actually reopen before the end of the school year.

An article in the Hechinger Report on April 3, 2020, made the shocking statement (at the time) that “students might not return to school this year” and asserted that “now is the time to start planning ahead…to catch students up when school reopens after coronavirus.” Even this article, one of the first to suggest that students would not return to buildings during the 2019–2020 academic year, did not have a full handle on how far out “after coronavirus” would be.

At the same time, phrases like “addressing learning loss,” “unfinished learning,” and “the COVID-19 Slide” filled the pages of our professional journals. Schools were being asked how they would address the COVID-19 Slide when, in reality, they were not even sure what form “school” would take the following week. Long-term planning could not occur because there were far more immediate matters to address, like “What are we going to do with students when they get online tomorrow morning?”

The good news is that we are now far more comfortable with our abnormal “new normal.” We realize that the pandemic is more of a marathon than a sprint, and we have generally accepted this. We have even built some useful new skillsets. We are far more adept with online platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams, and with our microphones, headsets, and virtual backgrounds. We have video production skills we never anticipated. The shock has passed, and now we are coping.

Nearly a year ago, I wrote a SmartBrief article on the potential of using summer to address learning loss. I remarked that many educators were likely “looking to make [summer 2020] more academic than the typical summer.” While some may have done this, I think I was wrong overall. Too many educators were still in the “shock phase” rather than the “coping phase,” and the idea of a deeply thoughtful summer learning program was too early then. But I think we are in a far better position to capitalize on the potential of summer 2021.

I say this because the dynamics have changed significantly. As I noted earlier, we are coping. Also, we better understand the gravity of the situation, because multiple studies have documented the scale of pandemic-related learning loss, particularly in math. Finally, the recent round of federal stimulus funds provides resources schools can use to support summer learning. In other words, we are far more capable of doing something this summer, our urgency is up because we’ve seen the drops in student performance, and we have funding available.

So, how do we capitalize on the summer of 2021 as an opportunity for “catching up?” Let’s explore specific options from Renaissance for both reading and math, as well as how assessments can inform the process.

Meeting students’ summer learning needs

First, let’s establish a framework for thinking about summer learning initiatives, ranging from those that are optional and less structured to those that are required and highly structured. This type of mindset is reflected in the current dialogue, which typically references “summer learning” rather than “summer school,” and includes considerations such as whether the experience is required or optional. We’ll base our recommendations on three levels of intensity:

- Level 1: This represents the less structured approaches that are designed to serve large numbers of students. The emphasis here is on keeping students regularly practicing reading and math skills, rather than on formal intervention. Students who participate may or may not be below a targeted level of proficiency. An example of this level is an optional, district-wide summer reading program open to all students.

- Level 2: At this intermediary level, participation may be either voluntary or mandatory. The needs at this level are not as extreme as at Level 3, but students targeted for such work are often below the desired level of proficiency. As a result, the instruction/intervention at this level is typically accomplished in a group setting (either large or small). This level may be referred to as an “acceleration academy” or “summer camp.”

- Level 3: At this level, we’re approaching the dynamics associated with formal—and mandatory—summer school, whether it’s offered in-person or remotely. Here, the desire is to intervene, catch students up, and address unfinished learning. The experience reflects a form of intervention and, as a result, often takes an individualized or small group approach. This level is sometimes called “high-dosage tutoring.”

With these three levels in mind, let’s consider reading and math practice over the summer months.

“Keeping the learning faucet open” for reading

For many students, the “summer slide” in reading is caused by the fact that they simply do not read during the summer months. This is often caused by a lack of access to books rather than a lack of motivation. In fact, as James Kim (2006) points out, “A synthesis of studies on summer learning loss showed that middle-income students enjoyed reading gains during the summer, whereas low-income students lost ground.”

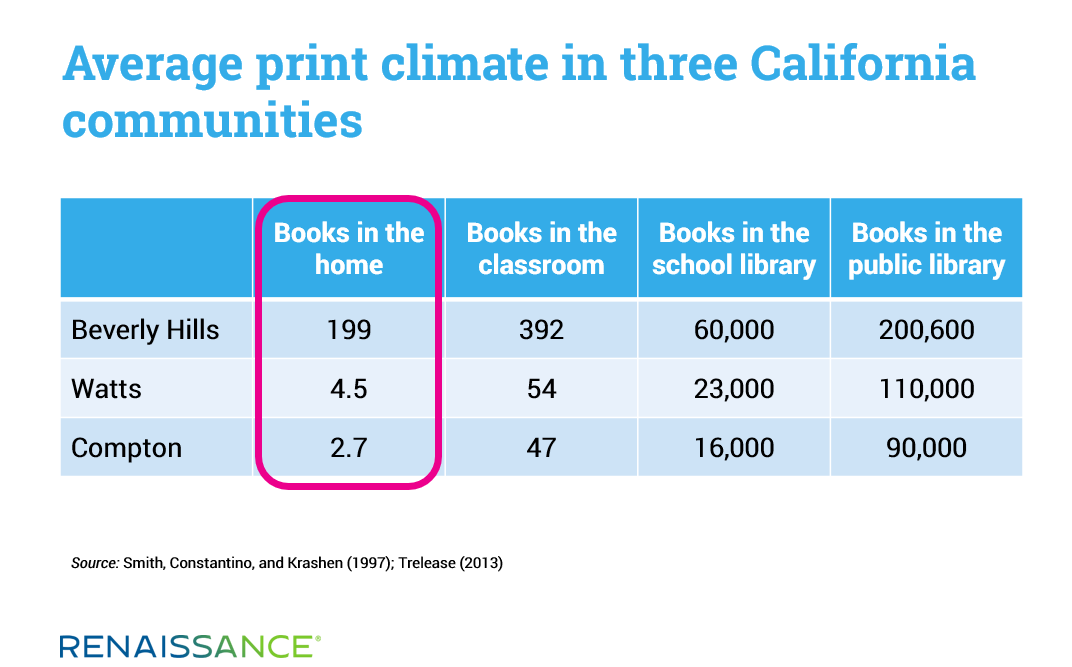

Perhaps there is no better example of the connection between socio-economic status and access to books than the analysis of three Los Angeles neighborhoods by Smith, Constantino, and Krashen (1997). They documented consistent and wide disparities between the number of books available in the home, classroom, school library, and public library (cited in Trelease, 2013). The higher the neighorhood’s poverty rate, the less access students had to texts. While these neighborhoods were just miles apart, students’ access to books was worlds apart—particularly in the home.

For these reasons, Kim (2006) remarks that “voluntary reading interventions, in which children receive free books and are encouraged to read at home, may represent a scalable policy strategy for promoting reading achievement during summer vacation.” He viewed this as a cost-effective option in the early 2000s, when the cost of providing print books to students exceeded the cost of providing access to thousands of titles through a digital library like myON today.

Consider the scale that could be achieved by providing a Level 1 summer program of myON access to all students, with regular check-ins and celebrations of summer reading. Districts serving emergent bilinguals would realize additional benefits as well. Because these students are learning English, myON’s natural-voice audio will help to further develop their listening skills as they read. For students whose home language is Spanish, myON’s Spanish books provide the opportunity to build knowledge and master skills that are transferable from Spanish to English. The research is clear in this area—learners who develop literacy in both the home and target languages achieve at the highest levels (Thomas and Collier, 2017).

Addressing learning loss in math

Last fall, our How Kids Are Performing report showed that the COVID-19 Slide was greater in math than in reading at every grade level and across every student demographic group. In a recent blog, my colleagues discuss why math was impacted the most. They also interview a middle-school teacher who uses the Freckle Math program to help prevent summer learning loss.

Freckle supports teacher-assigned, targeted math practice, with students working on the same activities. It also supports student-driven, adaptive practice, with students working at their own levels. This offers tremendous flexibility across all three levels of summer learning experiences:

- Level 1: In the same way that students (with guidance) choose the books they’d like to read over the summer, Freckle’s adaptive practice allows them to select (again, with guidance) the domains they’d like to work on. The program then continually adapts to their level, so they stay challenged and engaged as they work independently.

- Levels 2–3: In these settings, targeted practice—with the domains and skills selected by the teacher—helps to ensure that students focus on specific concepts and skills to address unfinished learning. Freckle’s Inquiry Based Lessons can be especially valuable at these levels, providing the opportunity for practice and small-group collaboration to help students secure new math skills.

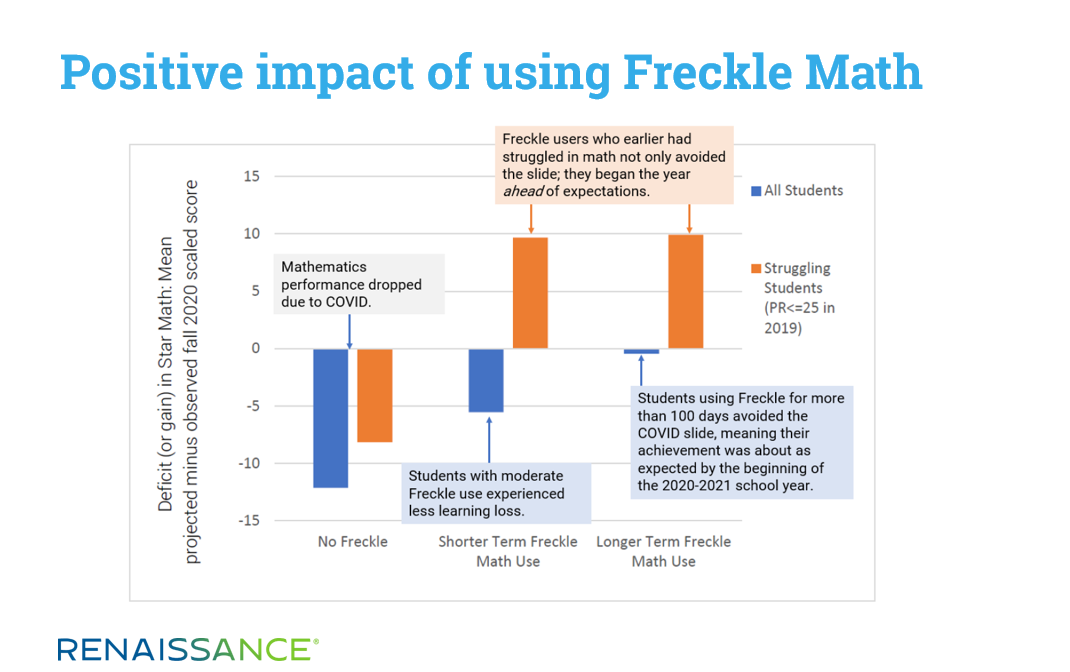

Recent research by Renaissance further validates the use of Freckle Math over the summer months. As shown in the graphic below, students who used Freckle Math during the spring and summer of 2020 were less impacted by the COVID-19 Slide than students who did not use Freckle. Moreover, the Freckle users who’d previously struggled in math actually exceeded expectations when they returned to school last fall.

Using assessment data to target support

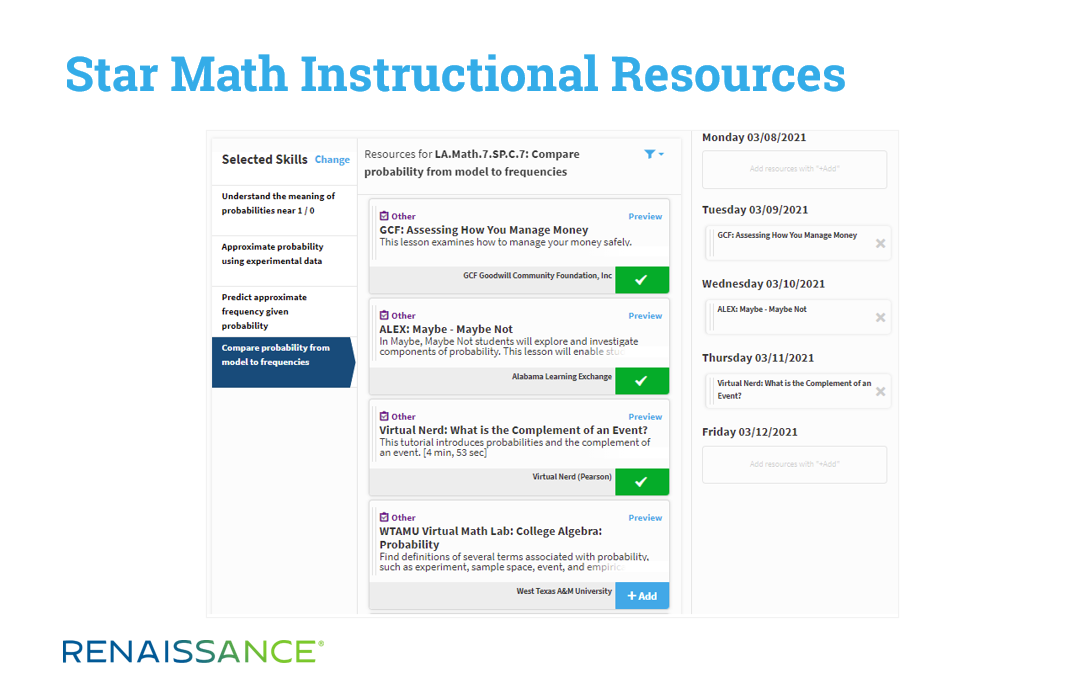

Finally, let’s explore how data from Star Assessments can factor into effective summer learning experiences. First off, if you’re regularly administering Star and you close out the core academic year with spring screening, you’ll have up-to-date instructional planning information available through Star’s reports and dashboards. This will be particularly helpful in deciding placements between the three levels, and in planning the groups and instructional topics for summer learning in Levels 2–3.

Also, given both the intensity and the “catch up” emphasis at these levels, a subsequent Star test at the end of the summer learning experience is also likely warranted. This may even be desired to document the efficacy of a Level 1 experience. A final Star test at the end of a summer program would serve to both gauge student growth over the summer months and offer a “fresh crop” of instructional planning and placement information for back-to-school.

Additionally, the many instructional and formative assessment resources embedded in Star will be tremendously useful in planning and monitoring the daily activities within a Level 2 or Level 3 summer learning experience.

Making the most of summer 2021

Despite deeply held beliefs about summer learning loss, the findings of some recent studies do not directly align with some of the more historical ones. Consider the following observations from a leading researcher on summer learning, Paul von Hippel (2019):

“So what do we know about summer learning loss? Less than we think. The problem could be serious, or it could be trivial. Children might lose a third of a year’s learning over summer vacation, or they might tread water. Achievement gaps might grow faster during summer vacations, or they might not.”

While the findings of some research on the scale of summer loss are conflicting, von Hippel stresses that this should not dissuade us from using the summer to catch students up and close learning gaps. He stresses that we do conclusively know that “nearly all children, no matter how advantaged, learn much more slowly during summer vacations than they do during the school year.” This means “that every summer offers children who are behind a chance to catch up. In other words, even if gaps don’t grow much during summer vacations, summer vacations still offer a chance to shrink them.” And “summer learning programs for disadvantaged children can take a bite out of achievement gaps, especially if students attend them regularly for several years.”

Let’s take these words as a call to make the most of our programs and resources this summer.

References

Kim, J. (2006). Effects of a voluntary summer reading intervention on reading achievement: Results from a randomized field trial. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 28(4), 335‒355.

Trelease, J. (2013). The read-aloud handbook. New York: Penguin.

Thomas, W., & Collier, V. (2017). Validating the power of bilingual schooling: Thirty-two years of large-scale, longitudinal research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 37, 1–15.

Smith, C., Constantino, R., & Krashen, S. (1997). Differences in print environment for children in Beverly Hills, Compton, and Watts. Emergency Librarian 24, 8–9.

Von Hippel, P. (2019). Is summer learning loss real?: How I lost faith in one of education research’s classic results. Available at https://www.educationnext.org/is-summer-learning-loss-real-how-i-lost-faith-education-research-results/

Visit our Summer Learning page for free resources to support your summer initiative. Also, please contact us to discuss purchasing or piloting myON, Freckle, or other Renaissance solutions. We’re here to help.