February 7, 2020

With Back to School in 2020, Renaissance will add a new set of measures to our industry-leading assessments of reading and mathematics. Teachers and schools will be able to select Star CBM, which provides curriculum-based measures of reading in grades K–6 and mathematics in grades K–3.

In this post, I’d like to address the three questions we hear most commonly when we’re discussing Star CBM with educators:

- What exactly is curriculum-based measurement?

- How do curriculum-based measures fit into a teacher’s or program’s assessment and instruction?

- Why did Renaissance decide to develop curriculum-based measures for reading and mathematics?

Defining “CBM”

Curriculum-based measurement, or CBM, has become a common, well-accepted part of educational assessment in elementary and secondary classrooms. Originally developed by Stanley Deno and colleagues in the 1970s (Deno, 1985; Tindal, 2013), CBM has distinguished itself as a psychometrically robust, practically efficient, and instructionally relevant tool for teachers to monitor progress and evaluate intervention in reading, mathematics, written expression, and a number of other content areas.

Deno (1985) identified four essential features of CBM—features that remain relevant and useful today:

- The measures have to be trustworthy and meaningful, meeting traditional psychometric standards for assessing educational achievement and making instructional decisions.

- The measures have to be simple and easy to use, so that teachers or classroom volunteers can and will use them with fidelity.

- CBMs should produce results that are easy to understand and that can be presented in ways that teachers, parents, and students can review and interpret efficiently.

- The measures should be relatively inexpensive and not require fancy materials or substantial training, so that they can be implemented in most (if not all) classrooms.

Following Deno’s work, an extensive research literature of more than 1,300 publications has investigated CBM’s design, psychometric features, and application. CBM has also become common in practice. Informal versions developed by teachers and programs, and more formal offerings available online and in the marketplace, are being used by teachers throughout the US.

CBM in the classroom: What you might see

You’ve probably seen the most typical form of CBM: a relatively short passage of text that the child is asked to read aloud to a teacher or other individual for one minute. The number of words the child read correctly in one minute serves as their score, and research shows that this simple score is a good indicator of the child’s overall reading skills.

Other CBMs abound, including forms where children solve mathematical problems, write stories in response to brief “starters,” name letter sounds, or read simple CVC words. In most cases, these tasks last for one minute, and some simple measure (for instance, problems or letter sounds correct) serves as the child’s score for that assessment.

Measures like these seem almost too simple to be useful. However, a long history of research, development, and use in thousands of classrooms across the country demonstrates clearly that CBMs can greatly assist teachers in both identifying students who would benefit from additional instruction, and monitoring progress for those students (and others) to assure that these interventions are working well.

This history of both rigorous research and teacher use is central to making Star CBM a strong resource.

How CBMs provide a “vital signs” check on academic growth

Stanley Deno was a professor of special education at the University of Minnesota and is widely credited with introducing the core ideas of both CBM and general outcome measure (GOM).

In the late 1970s, Dr. Deno was providing supplemental reading instruction to early elementary students in a Minneapolis public school. While he was generally confident in his selection and design of instructional practices, he wanted to be able to evaluate the effectiveness of his “good ideas” for each of the students he was teaching. In particular, he wanted measures that were as easy to use as a thermometer we use to detect illness, or a bathroom scale we use to monitor our weight—measures of “vital signs” for health and well-being. He also wanted measures that carefully reflected each student’s current level and degree of growth of academic achievement, took little time away from his focus on teaching, and could be done frequently to provide early and ongoing feedback about each instructional effort’s efficacy (Casey et al., 1988). At the time, however, there were few (if any) practices that met these requirements.

As Deno experimented with different approaches, his work began to focus on what became a defining feature of CBM and GOMs. In particular, he wanted to find ways for students to demonstrate their growing ability to perform better and better on a task that represented the year-end goal of their current instructional program. This decision was key: The idea is that task demands stay relatively constant over an extended period of time, and that the child’s improved achievement is represented by greater and greater levels of task completion.

Along with two colleagues (Deno et al., 1982), Deno first focused on ways to assess changes in reading achievement using brief, repeatable measures. From this research, a simple but remarkably strong candidate was identified, as mentioned earlier: The number of words a child read correctly from grade-level text in one minute produced a score that was very easy to collect, showed growth over time, and correlated at high levels with longer, standardized tests of reading (both decoding and comprehension).

From this first study, other investigators have demonstrated repeatedly that this simple measure, Words Correct per Minute from passage oral reading, is a robust and useful measure of reading—and a measure that can be used across weeks or grades to describe individual students’ growing reading competence. This solution, reading text for one minute and counting the number of words read in that minute (sometimes called “oral reading fluency”), has endured and is still a common feature of many CBM systems.

This early development in the area of reading led to comparable work in mathematics, spelling, and written expression (Deno et al., 1986). Interest in CBM spread rapidly, both in research and practice (Shinn, 1998; Tindal, 2013). Similar measures, including myIGDIs for Preschool and Infant and Toddler Individual Growth and Development Indicators, are available for preschool-aged children and are bringing this efficient and rigorous assessment to new programs and populations.

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, CBM had been widely accepted in educational practice, become a mainstay of planning and program monitoring in special education and Response to Intervention (RTI), and found its way into a host of teacher-prepared and commercially available products.

The development of Star CBM

Star CBM, the newest version of curriculum-based measures available for elementary students, rests squarely on Deno’s long line of research. In addition to measures of very early reading (e.g., letter-sound correspondence and simple word decoding) and mathematics operations (from numeral recognition to addition, subtraction, and multiplication), Star CBM assesses students’ oral reading achievement with passages written by Dr. Deno and his longtime colleagues Dr. Doug Marston, Dee Deno, and Debbie Marston. Each Star CBM can be administered either on- or offline, with options for the student to read from paper booklets or a digital screen, and for the teacher to score on paper (“by hand”) or using an easy-to-use digital interface.

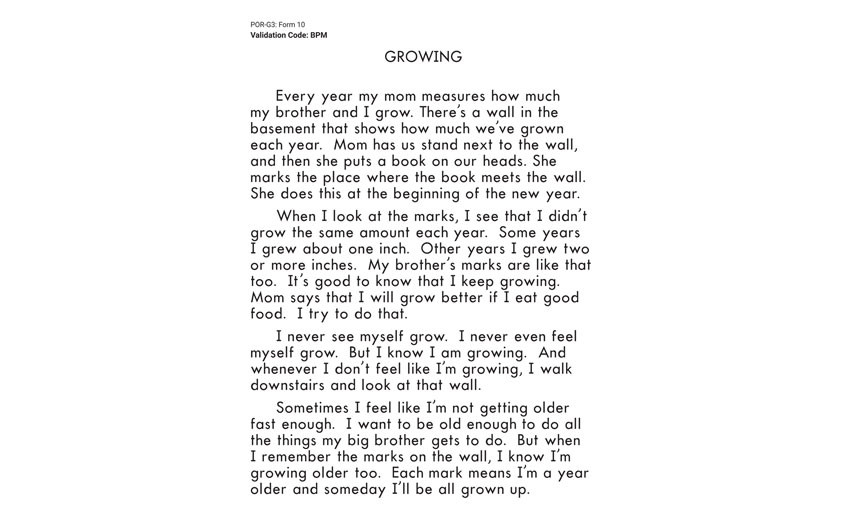

Sample Star CBM measure (Passage Oral Reading)

We are currently field-testing all measures, in both screening and progress monitoring applications, with thousands of children across the US. Results of this field test, along with ongoing input from teachers and administrators, will help us provide guidance for evaluating student performance during seasonal screening, plan for ongoing progress monitoring of individual students, and give teachers access to clear, useful reports of individuals and groups.

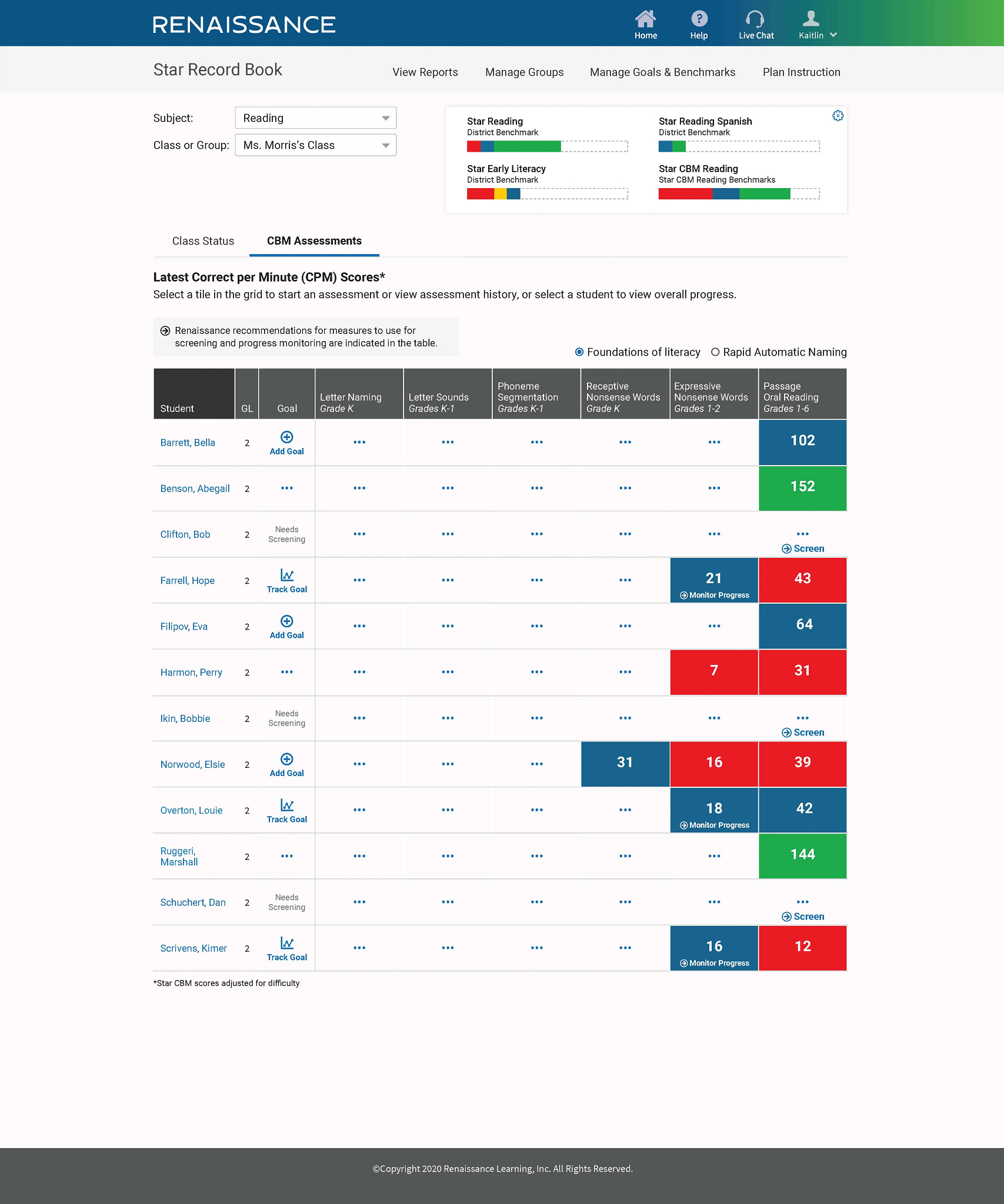

Sample Star CBM report

How CBM helps to accelerate learning for all students

As research and practice with CBM continued to expand, Lynn Fuchs and Stanley Deno provided a further refinement and description of the critical features of this approach to assessment. In particular, Fuchs and Deno argued that curriculum-based measures are part of a larger group of general outcome measures, or GOMs (Fuchs & Deno, 1991).

GOMs are designed to “provide teachers with reliable, valid, and efficient procedures for obtaining student performance data to evaluate their instructional programs” (Fuchs & Deno, 1991, p. 489). Fuchs and Deno go on to note that “the two most salient features of measuring general outcome indicators are (a) the assessment of proficiency on the global outcomes toward which the entire curriculum is directed, and (b) the reliance on a standardized, prescriptive measurement methodology that produces critical indicators of performance” (p. 493, emphasis added).

Fuchs and Deno’s (1991) description of GOMs provides an important foundation for distinguishing between essential and common features of the measures in this class. While the name “CBM” remains common, Fuchs and Deno’s analysis made clear that the focus is ongoing acquisition of a general academic skill taught by any particular curriculum—with less attention to specific skills that might be embedded in (and differentiate) any particular instructional program. Further, this focus on “general outcomes” enlarged the focus of researchers and practitioners to important developmental achievements that may not be taught by an identified curriculum. In particular, this opened the door to application of these ideas to children’s preschool development, where intentional and structured intervention is still somewhat uncommon.

Fuchs and Deno (1991) built on Deno’s earlier work, along with their substantial experience, to identify six key features of General Outcome Measures, including CBMs:

- Definition of a domain, or “general outcome,” of academic achievement, rather than specific skills. The focus is on a broadly defined task like “reading at grade level” or “language development for school success.”

- Assessment of domains and general outcomes where growth occurs over longer periods of time, most typically an academic year or more.

- Clear evidence of the social importance of long-term goals. In simple terms, these outcomes are often described in ways that parents and others understand and value.

- A focus on broad goals of a curriculum, as opposed to short-term instructional or other objectives.

- A common measurement model that extends across a long period of time, most typically an academic year or longer.

- Strong evidence of reliability within and across measurement occasions, and validity for individual measures as well as growth across time.

GOMs fit well with Renaissance’s mission of accelerating learning for all students by providing another set of tools for teachers to target the right intervention to the right students at the right time. We also are investing in ways to provide this information to teachers and programs starting in preschool to improve individuals’ and groups’ outcomes.

Supporting children from age 3 to grade 3

Renaissance offers general outcome measures of language, early literacy, and early numeracy development for preschool students who speak English or Spanish, and of reading and mathematics for students from kindergarten to third grade. These measures—myIGDIs for Preschool and Star CBM for elementary students—are designed for both seasonal screening and progress monitoring for those children receiving supplemental or individualized intervention. Unlike other measures, teachers administer myIGDIs for Preschool and Star CBM individually to students, allowing direct observation of the child’s ongoing development.

Together, myIGDIs for Preschool and Star CBM provide something entirely new in educational assessment: For the first time, educational programs will have access to measures that are both specifically designed and rigorously tested for either preschool or school-age students and that, collectively, describe a child’s growth and development from the early years of preschool through the early grades of elementary school. This aligned set of measures will help teachers identify and serve at-risk students earlier and monitor and adjust each child’s education to move toward important outcomes.

At the same time, these “age 3 to grade 3” measures will allow program managers and developers to better align services across multiple years in ways we expect will contribute to improved outcomes for the students they serve.

CBM + CAT: A comprehensive system of assessment

Test developers often remind us that no test is good for all circumstances. As a result, teachers and programs must select tests and measures that are well-suited to the goals they are trying to achieve. myIGDIs for Preschool and Star CBM provide teachers with access to general outcome measures during critical years of children’s academic development. They also complement the computer-adaptive Star Early Literacy, Star Reading, and Star Math assessments in programs that are responsible for students’ achievement over long periods of time. More choice in assessment means more information about students’ needs—and more opportunity to sharpen our focus on the students who most need our assistance. As educators, we can agree that this is a very good thing.

References

Casey, A., Deno, S., Marston, D., & Skiba, R. (1988). Experimental teaching: Changing beliefs about effective instructional practices. Teacher Education and Special Education, 11(3), 123–131.

Deno, S. L. (1985). Curriculum-based measurement: The emerging alternative. Exceptional Children, 52(3), 219–232.

Deno, S. L., Marston, D., & Tindal, G. (1986). Direct and frequent curriculum-based measurement: An alternative for educational decision making. Special Services in the Schools, 2(2–3), 5–27.

Deno, S. L., Mirkin, P. K., & Chiang, B. (1982). Identifying valid measures of reading. Exceptional Children, 49(1), 36–45.

Fuchs, L. S., & Deno, S. L. (1991). Paradigmatic distinctions between instructionally relevant measurement models. Exceptional Children, 57, 488–500.

Shinn, M. R. (ed.). (1998). Advanced applications of curriculum-based measurement. Guilford.

Tindal, G. (2013). Curriculum-based measurement: A brief history of nearly everything from the 1970s to the present. ISRN Education, 2013, 1–29.

Explore how Star CBM will give you actionable insight into your K–3 students’ developmental growth and instructional needs. Click the button below to get started.