September 8, 2023

The US has a long history of providing preschool programs for children prior to their entry into kindergarten and “formal education.” Nursery schools, childcare programs, Head Start classrooms, and the growing number of voluntary and universal preschool programs draw young children together into purposefully designed settings. These preschool settings can provide both academic and social-emotional foundations for children’s later school success.

It takes deliberate effort to produce these strong foundations, however. The question then becomes, “How can preschool experiences and services contribute to improved outcomes in elementary school and beyond, and what might be needed to make these contributions even larger?”

In this blog, we’ll explore how the design and delivery of preschool services—and particularly the assessment and data use practices embedded in preschool programs—contribute to short- and long-term benefits for individual children, especially those who might otherwise struggle to meet the academic and behavioral demands of the early elementary grades. We choose to focus on preschool assessment because of its potential to serve a central role in:

- Helping teachers identify those students who might benefit from additional support in early literacy; and

- Systematically and objectively evaluating whether these expanding preschool programs are stepping up to their special opportunity to provide a great start to successful academic careers.

The Science of Reading and preschool expansion

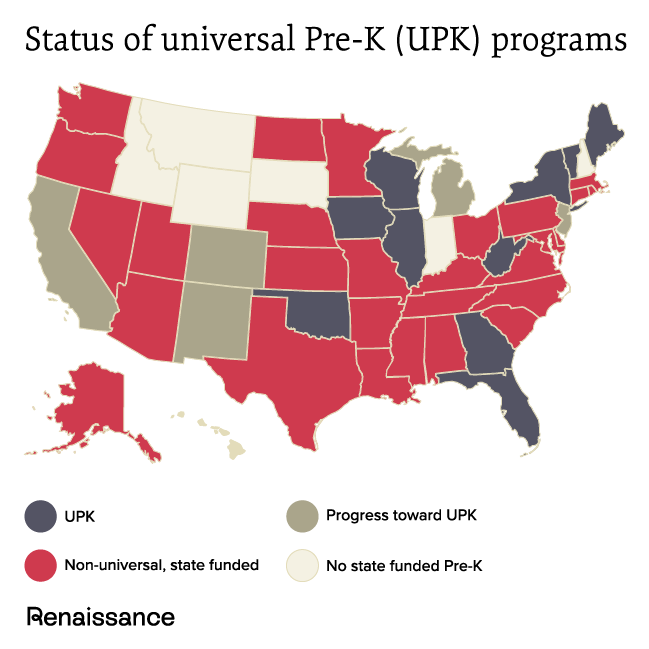

By the end of 2023, at least 34 states will have passed laws that provide some level of funding for voluntary or universal preschool services, primarily for 4-year-old children but increasingly for 3-year-olds as well:

These state laws have both expanded the numbers of children enrolled in formal preschool programs and increased the role of, and alignment with, local school districts in this effort. This expansion occurs as we continue to learn more about the ways in which young children’s development sets the foundation for, and contributes directly to, later learning and achievement (Cabell et al., 2023). Importantly, prior research offers guidance about how to teach and assess these foundational skills (Diamond et al., 2013; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).

At the same time, communities across the US are facing concern for academic outcomes—especially in reading—that are persistently low and demonstrate significant disparities across groups. Attention to how reading is taught in US schools has been covered in recent media reports, giving new prominence to understanding the Science of Reading. This idea of a “science” of reading captures the increasing focus by educators, parents, policymakers, and others on research about the most effective reading instruction practices.

The Science of Reading defined

The Reading League—a grass-roots organization founded by parents, educators, and others interested in improving US students’ reading skills—defines the Science of Reading as

A vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically-based research about reading and issues related to reading and writing….The science of reading has culminated in a preponderance of evidence to inform how proficient reading and writing develop; why some have difficulty; and how we can most effectively assess and teach and, therefore, improve student outcomes through prevention of and intervention for reading difficulties.

The Reading League, 2022

Related advocacy efforts have contributed to legislative action in many states. These new laws call for changes in preservice and in-service training of teachers, changes in approved curricula, and wholesale review and substantial reform in the ways reading instruction is provided (National Center on Improving Literacy, 2023; The Reading League, n.d.)

This body of knowledge also makes clear that nearly all children benefit from direct and systematic, explicit instruction in phonics and other foundational skills in the early elementary grades to support their journey to becoming independent and proficient readers.

Connecting the Science of Reading to preschool

Although the Science of Reading and its implications for teaching practices are generally focused on the elementary grades, research supports understanding how this science is equally important for preschool settings. We are learning more all the time about the characteristics of preschool children’s learning, and the strategies and tactics to support that learning, that in turn lead to reading proficiency. Importantly, research demonstrates that preschool literacy instruction practices that incorporate opportunities for children to learn and practice foundational literacy skills using both planned and incidental instruction are essential (National Institute for Literacy, 2008).

For instance, we have growing evidence that young children’s oral language development—a necessary and important foundation for reading proficiency (Scarborough, 2001)—is a direct product of children’s opportunities and interactions starting early in infancy (e.g., Fernald & Weisleder, 2011; Hart & Risley, 1995, 1999). Similarly, shared book reading provides opportunities for language development, alphabet knowledge, and phonological analysis development that similarly supports later learning to read (Hindman et al., 2014; Lefebvre et al., 2011; Neuman & Kaefer, 2018; Piasta et al., 2020; Stadler & McEvoy, 2003; Ziolkowski & Goldstein, 2008).

We are also learning more about the efficacy of systematic, teacher-led and child-focused classroom activities that support this critical early development (Diamond et al., 2013). In short, evidence-based, developmentally-appropriate preschool instruction is an important component of long-term student reading outcomes.

Preschool assessment and effective MTSS

In recent decades, we also have seen important innovations in service delivery models and the assessment practices that support them across the educational landscape. Although the nature of both preschool education and the students typically enrolled in preschool programs differ from those in the K–12 system, we have seen great adaptations of models often developed for older students that allow for differentiated services.

From early examples of these differentiated services (Coleman et al., 2006) to fully-specified practices for multi-tiered systems of support (Carta, 2019; McConnell, 2019; Hemmeter et al., 2020), early educators have strong guidance for the design, delivery, and evaluation of classroom-based programs. Not incidentally, these developments have coincided with growing value and sophistication in the assessment practices that support these models (Greenwood et al., 2011; Lonigan et al., 2011; McConnell et al., 2014; Moyle et al., 2013; Spencer et al., 2017).

How high-quality preschool assessment improves long-term reading outcomes

We have noted the growing but significant body of knowledge about the ways preschool programs and instruction can increase the odds of later academic success, especially in reading. The recent expansion of public preschool programs that incorporate research-based literacy instruction principles offers an important opportunity to improve all students’ long-term reading outcomes.

But to do this, and to do it well, we need to know who needs our attention and support, and in what areas that support is most likely to help. While teachers often have a “clinical” sense of students in their class, we know that reliance on teacher judgment alone can be inefficient and inaccurate, creating a risk that we will fail to identify and serve those children who most need our early support. It’s for this reason that formal assessment, tailored specifically to the characteristics and demands of preschool children and programs, is so important.

Moreover, researchers and assessment developers have perhaps paid too little attention to the unique demands of high-quality assessment with preschool children (McConnell & Goldstein, 2021; Will et al., 2019). It is not uncommon to hear professionals assert that assessment with preschool children will necessarily be unreliable—presumably because young children are often unpredictable! Certainly, the assessment dynamics for preschool children are different than for older children (e.g., a shorter attention span, and fewer ways they can respond to assessment tasks).

Additionally, some teachers of preschool children may have less experience with, or knowledge about, high-quality assessment practices. In our experience, these are not insurmountable challenges, but are instead the exact issues we need to consider when designing and evaluating assessments for our youngest students.

Assessments for preschool learners

Discover assessments from Renaissance designed for preschool programs.

Characteristics of a high-quality preschool assessment

When considering these factors, what are the characteristics of a high-quality assessment for preschool children? First and foremost, it is essential that these measures demonstrate strong psychometric characteristics:

- They must be reliable, producing similar information when gathered at slightly different times or by different teachers.

- They must be valid, or related to both short- and long-term goals that are important for young children.

- They must be useful, producing information that teachers and parents can easily interpret and, when necessary, use to plan action.

To do this, preschool assessments must take into account several key challenges that arise when working with young children and their teachers:

#1: Brief and engaging

Measures must be brief and engaging, and closely focused on core domains of interest. To keep assessment tasks brief, we have to minimize unnecessary content or activities that are sometimes thought of as making tasks more “fun” (but that also make them longer). Instead, designers have to make the assessment tasks themselves engaging, drawing children’s attention and participation in brief and high-value interactions.

#2: Easy to administer and score

Measures must be easy to administer and score by teachers who sometimes have less assessment experience—and always a shortage of time for training and practice. The early education workforce as a group has training and experience far more varied than their K–12 colleagues. Assessment developers must address this variety by making measures accessible and usable by the full range of preschool staff.

#3: Sensitive to growth

Assessments should reflect the developmental trajectory of young children’s lives by producing single-point measures (say, those collected seasonally throughout a school year) as well as more frequently repeated measures to show growth over time. This sensitivity to and demonstration of growth is both central to our thinking about preschool development, and an essential metric for thinking about all children’s paths toward preschool and elementary school proficiency.

Uses of a high-quality preschool assessment

With these three characteristics in place, a preschool assessment can be used to support great outcomes. These uses include:

- Seasonal screening, where we briefly sample behavior for every child in a program to check in on their developmental gains over time.

- Benchmarking of these screening measures, using empirical guidance to identify those children for whom some additional support or intervention may be needed to help achieve future developmental goals.

- Intervention and instructional planning, where we use screening and benchmarking results to both determine when and for whom to “lean in” and provide differential support in our classroom, and to direct that supplemental effort to areas where it is most needed.

- Progress monitoring, so that we can track the gains of children receiving supplemental intervention—and can adjust that intervention to make sure it is providing benefit.

How Renaissance supports your efforts with Star Preschool Literacy

As the breadth and quality of preschool programs continues to expand, and as the alignment of these programs with later K–12 educational goals continues to strengthen, more and more high-quality assessment tools will be available for preschool children. Renaissance is deeply committed to this expanding part of our educational system, as demonstrated by our growing array of assessments for preschool children.

As one example, we are excited to introduce Star Preschool Literacy, the first set of measures in a suite of assessments that will expand over the next year or two. Star Preschool Literacy provides screening and progress monitoring for English-speaking children one and two years prior to kindergarten, in key developmental areas that support later reading achievement:

- Oral language

- Phonological awareness

- Alphabet knowledge

- Comprehension

Star Preschool Literacy can be administered seasonally to all children, and it provides empirically derived benchmarks to help identify students for whom some additional support may be needed to make great developmental progress. Star Preschool Literacy can also be used for more frequent progress monitoring, to evaluate the impact of those additional supports so that teachers can adjust instructional practices when needed.

Star Preschool Literacy was systematically designed to gather reliable, meaningful, and useful information in preschool classrooms. The measures are brief, very easy to administer and score, with little prior training needed, and engaging to young learners. Perhaps more important, results are available immediately after the assessment is completed, with no additional data entry steps—allowing teachers to quickly move on to the classroom activities and instruction that truly drive developmental progress.

As mentioned earlier, Star Preschool Literacy is the first of what will be a suite of assessments for preschool children. Future developments will include direct assessment of oral language and early literacy skills for Spanish-speaking children, direct assessment of early numeracy development, and “whole child” teacher ratings. Designed for preschool children and preschool classrooms, these measures will be helpful tools for providing early education experiences that align with, and directly contribute to, later academic and school success.

Developing preschool assessments to support preschool development

Expanded access to preschool offers an opportunity to support more students through intentional and systematic educational programming. Laws, policies, and practices are quickly evolving to embrace these changes, and professionals engaged in this work are quickly expanding their capacity to contribute.

In order to maximize the benefits of preschool programs, high-quality preschool assessments are necessary so that preschool teachers will know what supports their children need. Through ongoing research, we can improve our ability to monitor young children’s growth toward great outcomes, and we can design our programs and instruction to facilitate this growth.

In future Renaissance blogs, we will continue exploring these developments, and we look forward to lifting up the stories of professionals, programs, and communities leading the way.

Learn more

Connect with an expert to discover how Star Preschool Literacy will support strong reading outcomes in your school or district.

References

Cabell, S. Q., Neuman, S. B., & Terry, N. P. (2023). Handbook on the science of early literacy. Guilford.

Carta, J. J. (2019). Introduction to multi-tiered systems of support in early education. In J. J. Carta & R. Miller Young (Eds.), Multi-tiered systems of support for young children: Driving change in early education (pp. 1–14). Brookes Publishing.

Coleman, M. R., Buysse, V., & Neitzel, J. (2006). Recognition and response: An early intervening system for young children at-risk for learning disabilities. Frank Porter Graham Center.

Diamond, K. E., Justice, L. M., Siegler, R. S., & Snyder, P. A. (2013). Synthesis of IES research on early intervention and early childhood education (NCSER 2013-3001). http://ies.ed.gov/ncser/pubs/20133001/pdf/20133001.pdf

Fernald, A., & Weisleder, A. (2011). Early language experience is vital to developing fluency in understanding. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 3, pp. 3–19). Guilford.

Greenwood, C. R., Carta, J. J., & McConnell, S. R. (2011). Advances in measurement for universal screening and individual progress monitoring of young children. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(4), 254–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815111428467

Hanford, E. (2022). Sold a story: How teaching kids to read went so wrong [podcast]. https://features.apmreports.org/sold-a-story/

Hart, B., & Risley, T. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Brookes Publishing.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. (1999). The social world of children learning to talk. Brookes Publishing.

Hemmeter, M. L., Ostrosky, M., & Fox, L. (2020). Unpacking the pyramid model: A practical guide for preschool teachers. Brookes Publishing.

Hindman, A. H., Skibbe, L. E., & Foster, T. D. (2014). Exploring the variety of parental talk during shared book reading and its contributions to preschool language and literacy: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort. Reading and Writing, 27(2), 287–313.

Lefebvre, P., Trudeau, N., & Sutton, A. (2011). Enhancing vocabulary, print awareness and phonological awareness through shared storybook reading with low-income preschoolers. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 11(4), 453–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798411416581

Lonigan, C. J., Allan, N. P., & Lerner, M. D. (2011). Assessment of preschool early literacy skills: Linking children’s educational needs with empirically supported instructional activities. Preschool Assessment and Intervention, 48(5), 488–501.

McConnell, S. R. (2019). The path forward for Multi-tiered Systems of Support in early education. In J. J. Carta & R. Miller (Eds.), Multi-Tiered Systems of Support for young children: A guide to response to intervention in early education (pp. 253–267). Brookes Publishing.

McConnell, S. R., Bradfield, T. A., & Wackerle-Hollman, A. K. (2014). Early childhood literacy screening. In R. J. Kettler, T. A. Glover, C. A. Albers, & K. A. Feeney-Kettler (Eds.), Universal screening in educational settings: Evidence-based decision making for schools. (pp. 141–170). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14316-006

McConnell, S. R., & Goldstein, H. (2021). Measurement built for scale: Designing and using measures of intervention and outcome that facilitate scaling up. In J. A. List, D. L. Suskind, & L. Supplee (Eds.), The scale-up effect in early childhood and public policy (pp. 301–319). Routledge.

Moyle, M. J., Heilmann, J., & Berman, S. S. (2013). Assessment of early developing phonological awareness skills: A comparison of the preschool Individual Growth and Development Indicators and the Phonological Awareness and Literacy Screening–PreK. Early Education & Development, 24(5), 668–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2012.725620

National Center on Improving Literacy. (2023). Schools and districts. https://improvingliteracy.org/school

National Institute for Literacy. (2008). Developing early literacy: Report of the national early literacy panel. https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/NELPReport09.pdf

Neuman, S. B., & Kaefer, T. (2018). Developing low-income children’s vocabulary and content knowledge through a shared book reading program. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 52, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.12.001

Piasta, S. B., Sawyer, B., Justice, L. M., O’Connell, A. A., Jiang, H., Dogucu, M., & Khan, K. S. (2020). Effects of Read It Again! in early childhood special education classrooms as compared to regular shared book reading. Journal of Early Intervention, 42(3), 224–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815119883410

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory and practice. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 1, pp. 97–110). Guilford.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9824

Spencer, T. D., Goldstein, H., Kelley, E. S., Sherman, A., & McCune, L. (2017). A curriculum-based measure of language comprehension for preschoolers: Reliability and validity of the assessment of story comprehension. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 42(4), 209–223.

Stadler, M. A., & McEvoy, M. A. (2003). The effect of text genre on parent use of joint book reading strategies to promote phonological awareness. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 18(4), 502–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2003.09.008

The Nation’s Report Card. (2022). NAEP Report Card: 2022 NAEP Reading Assessment: Highlighted results at grades 4 and 8 for the nation, states, and districts. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/highlights/reading/2022/

The Reading League. (n.d.). What is the science of reading? https://www.thereadingleague.org/what-is-the-science-of-reading/

The Reading League. (2022). Science of reading: Defining Guide. https://www.thereadingleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Science-of-Reading-eBook-2022.pdf

Will, K. K., McConnell, S. R., Elmquist, M., Lease, E. M., & Wackerle-Hollman, A. (2019). Meeting in the middle: Future directions for researchers to support educators’ assessment literacy and data-based decision making. Frontiers in Education, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00106

Ziolkowski, R. A., & Goldstein, H. (2008). Effects of an embedded phonological awareness intervention during repeated book reading on preschool children with language delays. Journal of Early Intervention, 31(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815108324808