August 14, 2020

You may not have heard of a French writer named Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, but you’ve probably heard his most famous phrase: “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” Karr, who was also a teacher and a lover of education reform, certainly never met a year like 2020. Because so much has changed, we might be better off asking, What’s actually stayed the same?

Businesses that had moved toward common work areas and open spaces are now transitioning back to individual offices and cubicles. Stores have erected plexiglass barriers, one-way aisles, and floor stickers to help maintain social distancing. Religious institutions are pondering how to “pass the plate” or “share the cup” when neither of these things is advisable from a public health perspective. Even our basic human instinct to welcome one another with a handshake or a hug is suppressed due to health concerns.

As we seek to find the “new normal” in so many areas of our lives, is it any wonder that, as educators, we must also consider the new normal for K–12 assessment? Suggestions of a possible “COVID-19 Slide” have given us heightened concern for gauging how students are performing and where they are in their learning. Yet many of the interim and formative assessment approaches we’ve historically relied upon involve being physically in the same location in order to administer the assessment under controlled conditions.

The purpose of this three-part blog series is to walk you through some of the most essential considerations for how assessments may need to change, given the dynamics of the 2020–2021 school year. We’ll begin with some high-level ideas around both interim and formative assessment, and we’ll answer the most common question that educators are asking us: Can Star Assessments be administered remotely?

The short answer is, absolutely. Virtual schools have been administering Star remotely for years. Last spring, when some assessment providers advised against or even restricted remote administration, we delivered between 29,000 and 167,000 Star tests per week remotely. You’ll find best practices for the remote administration of Star, along with links to helpful support resources, in our recent blogs on remote testing from the educator’s perspective and from students’ and parents’ perspectives.

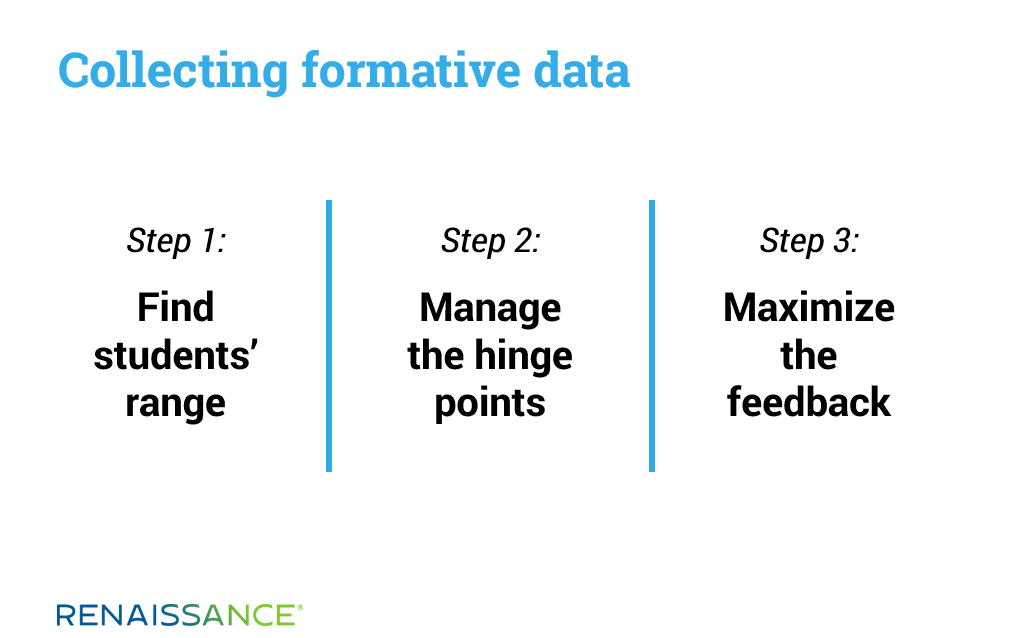

Now, let’s turn our attention to classroom-level formative assessment—the type of activities that should occur “minute by minute, [and] day by day” so that educators can use “evidence of learning to adapt instruction in real time to meet students’ immediate learning needs” (Leahy et al., 2005). In the following sections, we’ll walk through a three-step process for collecting formative data.

Before you begin, find students’ range

One strategy that will be especially useful this year—whether you’re teaching in-person or remotely—is to use range-finding questions. These are questions you ask before instruction that are chosen to find the range of students’ prior knowledge about a topic, or their level of proficiency with critical prerequisite skills. If a lesson requires prerequisite knowledge or skills, it’s always best not to assume these are already in place, especially in light of the disruption to learning caused by COVID-19 last spring.

Although this is a simple concept, range finding is often not done consistently. All teachers have faced a moment, usually about ten to fifteen minutes into instruction on a new topic, when they realize the students have no idea what they’re talking about. Often, this is because the students lack the necessary prior knowledge or prerequisite skills to learn the new content. If this happened regularly before COVID-19, there’s reason to believe that missing prerequisites and/or incomplete background knowledge will be even more of an issue in the year ahead.

While it takes time to develop and pose appropriate range-finding questions, you’ll save time in the long run by using them. For example, if a class of thirty students spends time going down an inappropriate instructional path for 15 minutes, 450 minutes of collective instructional time is lost. (That’s seven and a half hours!) Teachers who effectively use this strategy to find the range of their students’ prior knowledge are steered away from inappropriate instructional paths. Time in their class is consistently used in an effective manner, whether it’s proceeding with instruction they’ve confirmed the students are ready for, or making the deliberate decision to review necessary prior knowledge to ensure the upcoming lesson will be effective.

Managing a lesson’s hinge points

Once you’re past the “range-finding” phase, “hinge-point” questions become a valuable tool. Although we might not have previously considered the “hinge-point” of a lesson, we all know what it is. It’s the point after covering some content where a teacher purposefully stops teaching anything new and starts asking questions about what was just taught, trying to determine whether the students “get it.”

It is called a hinge-point because “the lesson can go in different directions depending on student responses” (Leahy et al., 2005). If responses to hinge-point questions are consistently correct, the teacher moves the class to the next instructional topic or to independent practice. If responses are consistently incorrect, reteaching is probably warranted. If responses are mixed, the teacher must decide what sort of quick “clean up” activities to use. Our point is that with any turn of the hinge, teachers’ practices and instructional decisions are informed by the data that students’ responses provide.

Perhaps the most difficult “turn of the hinge” to manage is the third scenario, when students’ responses are mixed. At this point, the teacher has a unique opportunity to involve students in peer instruction. If the teacher can judge that at least 50% of the students know the correct response, peer instruction will be highly effective, because there are enough students who understand the concept. Through peer instruction, these students can then help their classmates.

When peer instruction is used in this manner, everyone benefits. The students who grasp the content at the hinge point gain a deeper understanding through explaining the content to someone else in their own words. Their peers who were struggling at the hinge point will be brought up to speed. Additionally, many teachers report that in these instances, peer instruction is superior to anything they might have offered in reteaching the content themselves. This is not surprising because, when teaching their peers, students translate the content into more “kid-friendly” terms.

Note that peer instruction may be more challenging in a distance-learning or hybrid environment, but it’s certainly not impossible. Online video conferencing tools often include “breakout rooms” or similar features that enable just this type of small-group collaboration.

Maximizing the value of feedback

Finally, no matter which type of question we’re asking students, our goal should be to maximize the amount of feedback we receive. We want to sample as broadly as we can and hear from as many students as possible to make sure the instructional decisions we’re making at the moment (e.g. move on, linger, re-teach) are based on as much data as possible. Having individual students raise their hands to respond to teacher-posed questions is one of the least effective ways of getting good data for instructional planning. Students who are confident in their learning raise their hands, while others avoid exposing their lack of understanding—giving teachers an inaccurate feel for the learning that is or is not occurring. Our goal should be to hear from many if not all students at key points.

With polling and other response features built into Zoom and other online video platforms, the infrastructure for an “all response system” is already in place for remote teaching. In the physical classroom, options might include responding via websites like Mentimeter or using low-tech options like small white boards or exit passes (e.g., “Write a response to one question on an index card and hand it to me on your way out of the door”). You can also use Star Assessments to deploy, track, and report data on a variety of assessment items used for formative purposes.

Assessment resources for the year ahead

While we don’t know exactly what awaits us in terms of student performance at back-to-school 2020, it’s reasonable to assume that there will be wider performance gaps and that important prerequisite skills will be missing. During any school year, using high quality interim and formative assessments is highly advisable. In 2020–2021, these assessments will be critical. This is our new normal.

In the next blog in this series, we discuss two key features of effective teaching and learning in the year ahead: Knowledge of the skills that matter the most, and the ability to easily track students’ progress toward mastery of these skills. To read this blog, click here. If you’re looking for more resources, check out the book Embedded Formative Assessment by Dylan Wiliam, which includes more than 50 formative assessment strategies.

References

Leahy, S., Lyon, C., Thompson, M., & Wiliam, D. (2005). Classroom assessment: Minute by minute, day by day. Educational Leadership, 63(3), 18–24.

Learn more

Are you up-to-speed on everything that Star Assessments have to offer? Learn more about Star curriculum-based measures, Star Assessments in Spanish, and other features that will help you to accelerate student learning this year.