October 16, 2014

Think back to the last really rigorous and complex task that you worked on. Did you develop and complete it from start to finish all on your own? Or did you perhaps talk with colleagues, look at models, or seek out related information or examples from experts? Did you develop drafts and get feedback on your work before you felt satisfied that you had fulfilled expectations?

Over two decades ago I heard Dr. Howard Gardner make a comment that has stayed with me all these years: “Every complex task in life is a project, and we rarely—if ever—do them alone.” I think the point he was making then, and one that has since been supported by cognitive research, is that we can tackle much more complex tasks when we work on them with others—especially when we are learning how to do those tasks  (Hess & Gong, 2014).

(Hess & Gong, 2014).

So why is it that educators seem to hesitate to provide some form of scaffolding when presenting students with more complex and rigorous tasks? Trust me when I say this: Scaffolding is not cheating! It’s just good instruction to scaffold for deeper understanding.

First, let’s define scaffolding

There are several forms that scaffolding can take. Scaffolding can come from any aid that supports thinking and analyzing the content, e.g., teacher, peers, content, task (such as breaking it down into manageable parts), and materials. The purpose is to provide support during learning in order to gradually remove the support when learning becomes solidified and/or the learner becomes more independent and able to transfer learned skills to new situations. This is why it’s often referred to as “scaffolded instruction.”

Types of scaffolding strategies include:

- Teacher/peer scaffolding. More support is provided when introducing new concepts, tasks, or thinking strategies (e.g., developing a mathematical argument); support is gradually removed over time; peer scaffolding would include peers reading and discussing together, challenging each other’s ideas/solutions, or solving complex problems in more than one way. Guided think-alouds are another example of teacher scaffolding.

- Content scaffolding. Introducing simpler versions of the (essence of) content/concepts before more challenging (deeper or broader) ones are tackled.

- Task scaffolding. Introducing simpler tasks before tackling more challenging ones or expecting new applications, and breaking complex tasks into smaller steps.

- Materials scaffolding. Using graphic organizers, study guides, and visual cues, which leads to seeing predictable patterns in texts or problem-solving contexts.

Rigor, depth of knowledge, and scaffolding

The most common misconception I hear about rigor and depth of knowledge (DOK) goes something like this: “Not all students can think deeply,” or “Young students cannot think deeply before they have ‘mastered’ their math facts,” or “Students don’t need help to get to deeper thinking.” I say, wrong, wrong, wrong.

Here is what some of the research says:

- Engaging in “a complex task” with supports/scaffolding is an essential step along the way to proficiency.

Think Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development (ZPD). Social interaction, group problem solving, and meaningful mathematical discourse will move students from what they can do today with help to what we want them to be able to do tomorrow, independently.

Think Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development (ZPD). Social interaction, group problem solving, and meaningful mathematical discourse will move students from what they can do today with help to what we want them to be able to do tomorrow, independently. - Do that challenging task with others first. DOK 3 tasks (e.g., using calculations, diagrams, and more than one approach to develop a mathematical argument) and DOK 4 tasks (e.g., class projects that integrate math and science) are not meant to only be done independently, especially at first.

- Oral language and meaningful discourse supports reasoning. (This might be in response to questions like, Why do you say that? Can you provide some evidence for that? Would you like to change your thinking about that? Why?)

- Small group discussions and problem solving provide simultaneous engagement—all students are talking and thinking. Whole class discussions should be minimized and used for groups critiquing groups. Don’t let the class “workhorses” do the thinking for everyone!

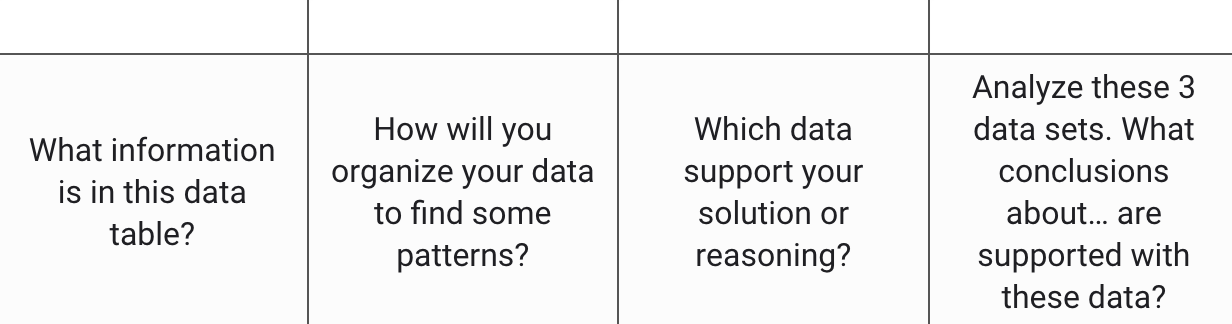

One easy strategy is to plan questioning and formative probes from DOK 1-2-3-4 over the course of a lesson or unit of study. (See the table below for an example.) Consider all DOK levels in your planning, even if you don’t use all of them in the lesson or unit. Sometimes start with the larger, more interesting and challenging question; other times start small, but end big (meaning deep).

Sources

Hess, K., & Gong, B. (2014). Ready for college & career? Achieving the Common Core standards and beyond through deeper student-centered learning (Research syntheses). Retrieved from http://www.nmefoundation.org/resources/scl-2/ready-for-college-and-career

Hess, K., McDivitt, P., & Fincher, M. (2008). Who are those 2% students and how do we design items that provide greater access for them? Results from a pilot study with Georgia students. Paper presented at the 2008 CCSSO National Conference on Student Assessment, Orlando, FL. Tri-State Enhanced Assessment Grant: Atlanta, GA. Retrieved from http://www.nciea.org/publications/CCSSO_KHPMMF08.pdf