September 10, 2021

The disproportionate effect of the pandemic

As a Latina and African American woman from the New York City area, I knew the COVID-19 pandemic would have a disproportionate effect on people from my community even before the media outlets announced it. Higher rates of comorbidities, limited access to high quality healthcare, and densely populated neighborhoods almost guaranteed this would be the outcome. Likewise, when education experts warned that the pandemic would negatively impact student academic performance, I knew the magnitude of this impact would be greatest for students from my community. The results from Renaissance’s latest How Kids Are Performing report confirm this.

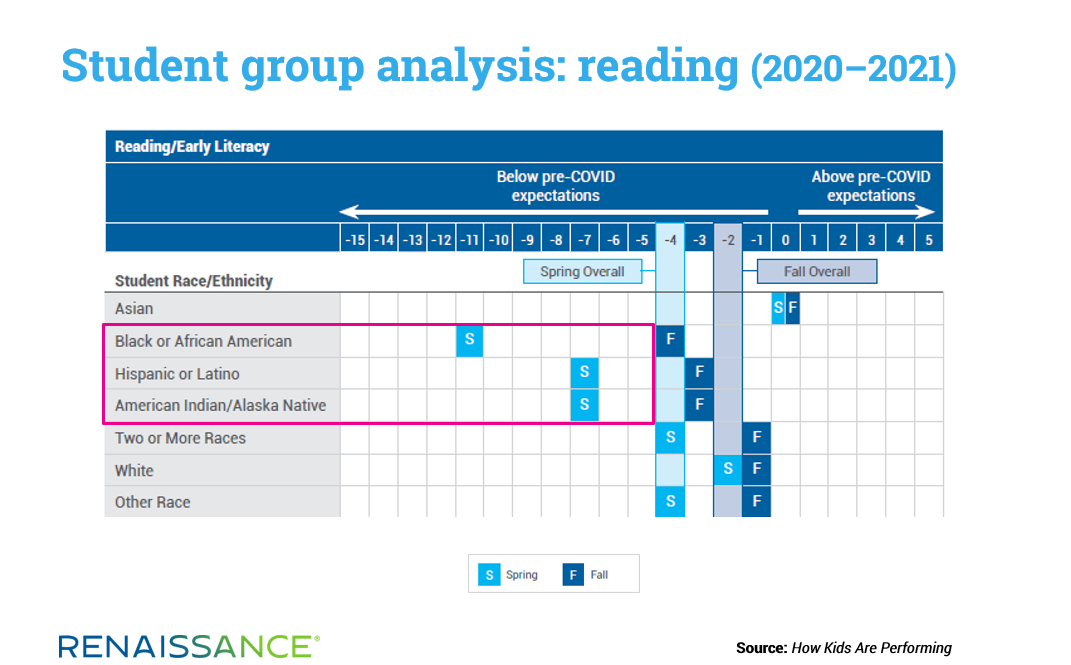

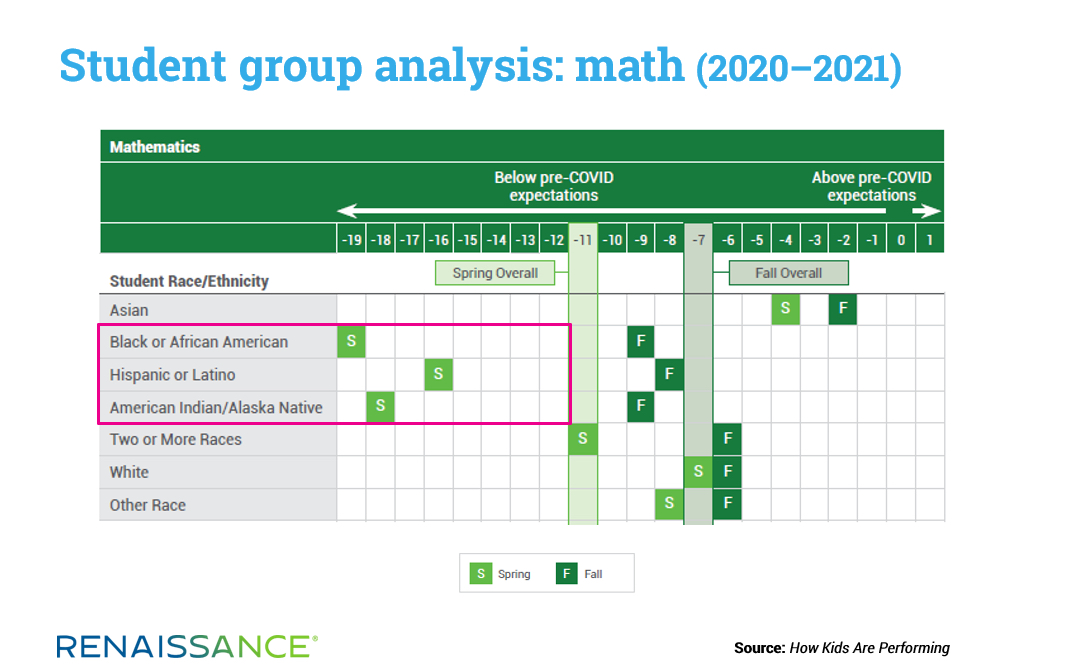

The new, full-year edition of How Kids Are Performing, which analyzes Star Assessments data for over 3.3 million students across the US, demonstrates the pandemic’s impacts on student learning. An analysis of students’ actual Spring 2021 performance compared to expectations reveals that, overall, students were at the equivalent of 4 percentile ranks (PR) below pre-pandemic expectations in reading, and 11 PR lower than expected in math. While these numbers are alarming in themselves, a closer look at the disaggregated data tells an even more troubling story.

Black students were the most impacted by the pandemic, performing 11 PR below pre-pandemic expectations in reading and 19 PR below expectations in math. Hispanic students also experienced disproportionate impacts, performing 7 PR below expectations in reading and 16 PR below expectations in math. Similarly, Native American students performed 7 PR below pre-pandemic expectations in reading and 18 PR below expectations in math. The pandemic has clearly exacerbated an already existing and pervasive academic performance gap.

The How Kids Are Performing report highlights the urgency to accelerate learning for all students in a way that is both equitable and responsive. The disproportionate impact experienced by marginalized communities calls for an equally intensified focus on these students when developing strategies to improve academic performance. When considering how to approach this, one thing is evident: more of the same will not suffice. Because these performance gaps existed prior to the pandemic, simply assigning more classwork to students will clearly not yield the desired results.

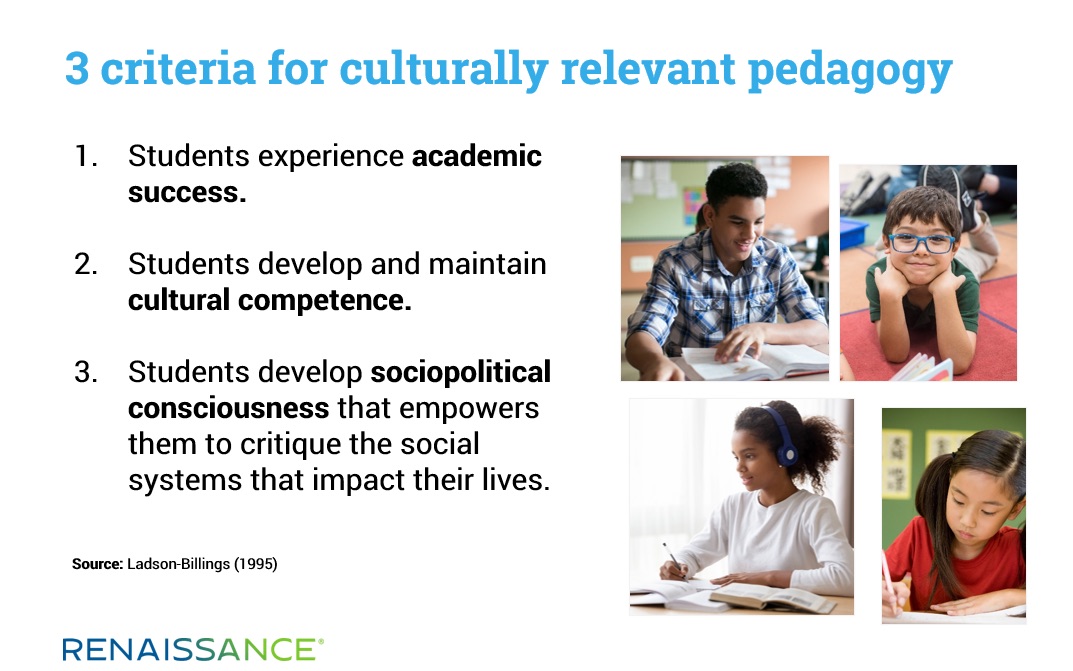

Instead, successful solutions will likely require teachers to find creative methods of increasing engagement and making the connections between classroom material and students’ personal lives more salient. Such is the basis for culturally relevant pedagogy, an educational approach coined by Gloria Ladson-Billings in 1995 and researched by scholars in the decades that followed.

So, what does culturally relevant pedagogy involve—and why will it be so important this school year?

Understanding culturally relevant pedagogy

Culturally relevant pedagogy (CRP) is grounded in the belief that students perform at higher levels when the content builds on the cultural assets they bring to the classroom. For this reason, it calls for educators to de-center mainstream (i.e., White, middle class, American) culture and to instead center students from typically marginalized communities. Relevant and personally meaningful content increases student effort, engagement, motivation, and performance (Howard, 2001; Renninger, Ewen, & Lasher, 2002). CRP has also been linked with improved graduation rates, GPAs, and college acceptance rates for high school students (Howard & Terry, 2011; Whiting, 2009).

Culturally relevant pedagogy rests on three criteria, as shown in the graphic below. Let’s explore these criteria and initial steps educators can take to implement CRP in their practice this year.

Prerequisites to culturally relevant pedagogy

To practice culturally relevant pedagogy, educators must first understand their own culture and the role it plays in their lives. CRP entails developing students’ cultural competence, or the knowledge of and appreciation for their own culture to understand and appreciate the cultures of others (Ladson-Billings, 2014). However, educators cannot develop students’ cultural competence without understanding their own cultural systems, social norms, and ways of learning. Here are a few steps educators can take to prepare:

- Understand your culture and its impacts on your life. Engage in reflective practices that allow you to explore your own culture and the role it has played in shaping your views, beliefs, and interactions with others. Educators can practice self-reflection using Weigl’s (2009) protocol. I also recommend the Washington State Professional Educator Standards Board’s comprehensive set of cultural competency standards that span pre-service and beyond.

- Understand your students’ cultural backgrounds. Take some time to get to know your students personally and to learn about their lives outside of school. Do not assume students of the same race share similar traditions. The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) recommends attending local events, joining social groups, and engaging parents and families in the classroom as ways to develop a deeper understanding of students’ personal lives.

Now, let’s look in detail at the three criteria for CRP.

1. Expect academic success

The success of CRP relies on the expectations and standards for learning set by the educator. No amount of “relevance” will promote academic success if the curriculum is not rigorous enough for students to meet or exceed grade-level expectations. Here are some things to keep in mind for this first criterion:

- Establish high expectations for all students. Teachers must have confidence in their students’ academic potential, believing that all students can reach high standards. Unfortunately, high expectations for all students regardless of race is not always the case (Tenenbaum & Ruck, 1997). When practicing CRP, it is essential that teachers become aware of any conscious or unconscious biases they may possess and how these biases impact their grading, discipline, and academic expectations for students. The Graide Network offers insight into how bias may manifest itself in the classroom, and the Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning offers recommendations and resources for teachers seeking to eliminate bias from their practice.

- Show students you believe in their competence and value their input. Show students you value the assets they bring to the classroom by incorporating their feedback into the lesson. This contributes to a feeling of “being known,” or mattering, which describes students’ perceptions of whether their input is considered during instruction, whether they are taken seriously, and whether teachers are genuinely interested and invested in their success (Tucker, Dixon, & Griddine, 2010; Chhuon & Wallace, 2014).

2. Center students in the lesson

Perhaps the most recognizable aspect of culturally relevant pedagogy is the centering of marginalized students in daily lessons. CRP recognizes the unique experiences each student brings to the classroom and acknowledges them as assets to be valued and built upon rather than overlooked. Such teaching enables students to draw meaningful connections between class material and personal experiences. Further, these pedagogical practices have the potential to contribute to an education system that is truly representative of its diverse learners.

How can you center students in a lesson?

- Review curricular materials to determine whose culture is centered and affirmed. Conduct an audit of books on the syllabus. Are the “literary classics” written by mostly White men? Are works written by Latino authors reserved for Hispanic Heritage Month? Do the contributions of African Americans focus mostly on civil rights? Educators should include culturally relevant curricular materials throughout the academic year and across content areas. Continual affirmation encourages students to develop a sense of integrity in their culture that allows them to “be themselves” during the learning process (Howard & Terry, 2011). Additionally, leverage the relationships with students’ families, engaging them in the lesson as frequently as possible. Acknowledging students’ parents and community members as holders of knowledge helps students to further value their own culture.

- Ensure cultural relevance extends beyond the diversity of the characters in books. Over the years, scholars have warned against oversimplifying CRP to “books about people of color, having a classroom Kwanzaa celebration, or posting ‘diverse’ images” (Ladson-Billings, 2014). While these initiatives transform curricular content into mirrors that allow students to see themselves celebrated in the materials, CRP goes beyond this and incorporates the cultural tools and learning styles of students in all aspects of the lesson. Consider how your students prefer to learn and the methods in which they prefer to demonstrate their mastery. For example, given research suggesting African American students prefer communal learning techniques (Dill and Boykin, 2000), teachers may find Hammond’s suggestions to gamify and storify new content helpful. Understanding how your students navigate their social world enables educators to adapt their lessons to make them sticky and more engaging.

3. Encourage sociopolitical engagement

Culturally relevant pedagogy engages students in critical analyses of social systems and structures affecting marginalized communities and groups of people (Ladson-Billings, 1992). Educators practicing CRP view education as a form of social justice and instill this in their students, empowering them to make change in their communities through their education. The development of this sociopolitical consciousness is a critical aspect of CRP, though it is frequently diluted or omitted from practice. Here are some ways teachers can develop this sociopolitical consciousness in their students:

- Allow students to identify concerns affecting their community. Give students the agency to critically examine the world around them. Rather than mandate a particular topic, encourage students to analyze their communities and identify systems that impact them. Some examples may include an examination of the availability of AP course offerings in their high school compared to more affluent schools, the school’s uniform policy, or the proximity to a fresh food market if the school is located in a food desert. Teaching for Change offers a variety of suggestions for students seeking to learn about social justice.

- Empower students to advocate for change. Students should not stop at critiquing social systems; they must also feel empowered to make positive change. Educators should find developmentally appropriate ways of encouraging students to advocate for their communities, whether through face-to-face interactions or online initiatives. Students can write letters to congressional leaders, create a community newsletter, put on plays and art exhibits, and more. Learning for Justice is a great source for educators seeking to embed social justice across the curriculum.

Culturally relevant pedagogy in the year ahead

Culturally relevant pedagogy has been researched, implemented, and revisited for decades. Its popularity has surged once again as we consider the most effective ways to improve the performance of those most impacted by the pandemic. Decades of research on culturally relevant pedagogy demonstrate its benefits on student engagement, interest, and performance. It must be noted, though, that CRP is not a quick fix. Teachers cannot simply add books with Black characters or analyze a hip hop song’s literary devices and expect success. CRP requires high academic standards, the development of cultural competence in both teachers and students, and a firm belief in the power of education to bring social justice. Furthermore, it requires a long-term commitment and application across all content areas. Still, when implemented with fidelity, CRP has the potential to transform students into high performing, civically engaged scholars with high cultural competence—which will be key to making up lost ground due to the pandemic.

Chhuon, V., & Wallace, T. (2014). Creating connectedness through being known: Fulfilling the need to belong in US high schools. Youth & Society, 46(3), 379–401.

Dill, E., & Boykin, A. (2000). The comparative influence of individual, peer tutoring, and communal learning contexts on the text recall of African American children. Journal of Black Psychology, 26(1), 65–78.

Howard, T. (2001). Telling their side of the story: African American students’ perceptions of culturally relevant teaching. The Urban Review, 33(2), 131–149.

Howard, T. & Terry, C. (2011). Culturally responsive pedagogy for African American students. Teaching Education, 22(4), 345–364.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1992). Reading between the lines and beyond the pages: A culturally relevant approach to literacy teaching. Theory into Practice, 31(4), 312–320.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: a.k.a. the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84, 74–84.

Renninger, K., Ewen, L., & Lasher, A. (2002). Individual interest as context in expository text and mathematical word problems. Learning and Instruction, 12, 467–491.

Tenenbaum, H., & Ruck, M. (2007). Are teachers’ expectations different for racial minority than for European American students? A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 253–273.

Tucker, C., Dixon, A., & Griddine, K. (2010). Academically successful African American male urban high school students’ experiences of mattering to others at School. Professional School Counseling, 14(2), 135-145.

Weigl, R. (2009). Intercultural competence through cultural self-study: A strategy for adult learners. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33, 346–360.

Whiting, G. (2009). Gifted Black males: Understanding and decreasing barriers to achievement and identity. Roeper Review, 31(4), 224–233.

Learn more

Download the full-year edition of How Kids Are Performing for more insights on the most urgent instructional needs this year. Also, click the button below to explore 4 additional steps for accelerating learning this fall.