May 8, 2018

Once you’ve found a timely, trustworthy assessment with a well-designed learning progression, it’s time to start assessing your students!

. . . or is it?

Over-testing is a real concern in today’s schools. A typical student may take more than 100 district and state exams between kindergarten and high school graduation—and that’s before you count the tests included in many curriculum programs and educator-created tests.

How can you balance the assessments that help inform instruction with ensuring enough time is reserved for that instruction? When should you assess your students? Which students should you assess? How frequently? What factors should drive your assessment schedule?

These questions often challenge educators, in part because there are no universal answers save “It depends.” It depends on the specific needs and goals of your school or district. It depends on your students, the challenges they face, and the strengths they can build on. It depends on how your team approaches teaching and learning. It depends on so much.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t any answers at all. We looked at research, consulted with experts, and found a few insights we think will help you discover the right rhythm for your assessment schedule.

Let your assessment questions guide you

The assessment process isn’t just about gathering data—more critical is using that data to answer questions and make decisions. Educational professors John Salvia, James E. Ysseldyke, and Sara Witmer define assessment as “the process of collecting information (data) for the purpose of making decisions for or about individuals.” It follows that if there are no decisions to be made, there is no reason to gather the data. Eric Stickney, an educational researcher at Renaissance®, summarized this simply as “Never give an assessment without a specific question in mind.”

Never give an assessment without a specific question in mind.

The questions you’re trying to answer will help determine if you should assess students, which students to assess, what type of assessment to use, and when and how often to use it. For the purposes of this article, we’re grouping assessment-related questions into three broad (and sometimes overlapping) categories: the “discover” questions that most frequently arise before learning begins, the “monitor” questions that occur during learning, and the “verify” questions that happen after a stage of learning has ended.

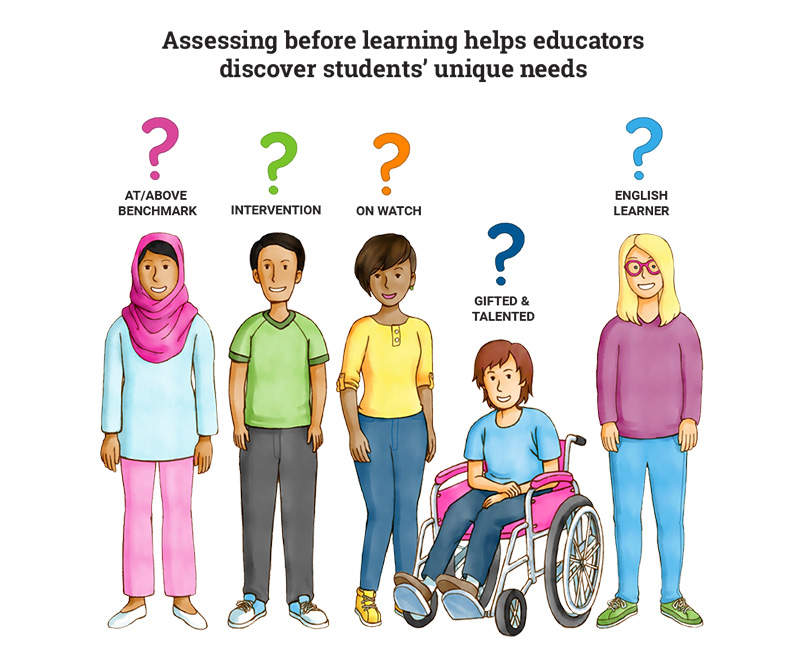

Assessing to discover your students

Sometimes you have questions about what your students have learned—but sometimes you have questions about the students themselves. These latter questions arise most frequently before learning or a new phase of learning (e.g., new school year, new semester, new unit) has begun. Because they’re generally broad, opened-ended questions that educators ask to learn more about their students or uncover issues that may otherwise have gone unnoticed, we can think of them as “discover” questions. Discover questions—and the assessment data that answers them—can help educators identify the unique traits of an individual student or understand the composition of a group of students.

- Where is the student on my state-specific learning progression?

- Is this student ready for grade-level instruction?

- Is he on track to meet state standards?

- What are his strengths or weaknesses?

- What learning goals should I set for this student?

- Is additional, more targeted, testing needed?

- Is the student a candidate for intervention?

- Which skills is he ready to learn?

- How does he compare to his peers?

- Is he achieving typical growth?

- Did he experience summer learning loss?

At the group level, discover questions include:

- What percentage of students are on track to meet grade-level goals?

- How many will likely need additional support to meet learning goals?

- What percentage qualify for intervention?

- How many should be further evaluated for special education service needs?

- How should we allocate current resources?

- Are additional resources needed?

- How do specific subgroups, such as English Language Learners, compare to the overall student population?

- Are there achievement gaps between different student groups?

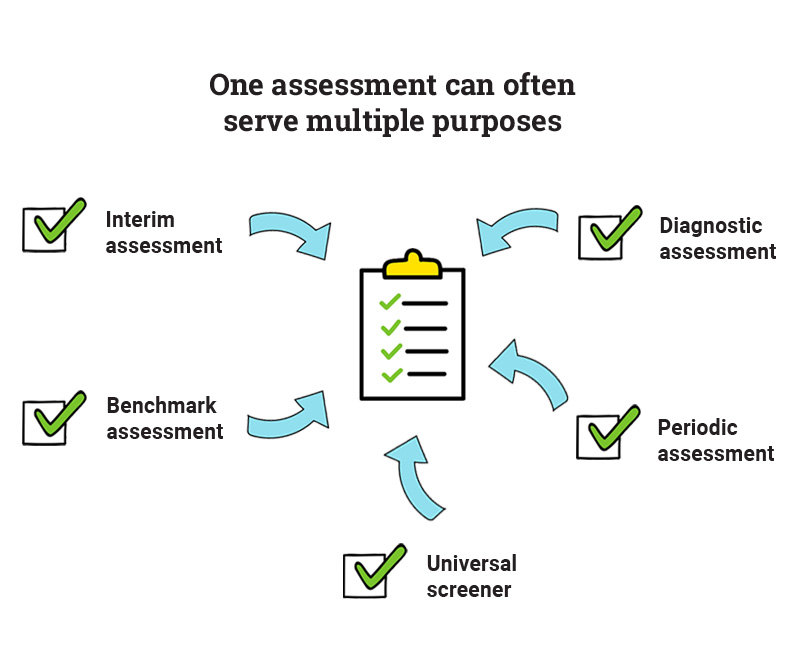

There are several types of assessment that can be used to answer discover questions, including interim assessments, benchmark assessments or benchmarking assessments, universal screeners or universal screening assessments, diagnostic assessments, and periodic assessments. (Note “periodic assessments” aren’t actually an assessment type per se, but rather a description of how an assessment is used: periodically.)

One thing to remember is that most of these terms describe how an assessment and its results are used rather than its content or format—one test can often serve multiple purposes! While this may make things confusing when trying to distinguish between the types, there is also a huge benefit to both educators and students: When one assessment can serve multiple functions, students can take fewer tests overall and more time can be devoted to instruction.

How often you use these assessments depends on how often you find yourself asking discover questions and how often you think the answers may change. If you’re not asking questions or if not enough time has passed for the answers from the last assessment administration to have changed, then it’s probably not ideal to assess students again.

In addition, if you’re not prepared to act on the assessment data or if you’re unable to make changes based on assessment data, then we would caution against assessing your students. Assessment for assessment’s sake is not a practice we can recommend; the ultimate goal of assessment should be to inform educators and benefit student learning.

Although only you can know the assessment timing and frequency that’s right for your students, many schools and districts opt to assess all students two to five times a year for “discover” purposes. Among these, most will assess near the beginning of the school year (which is especially helpful if you have new students without detailed historical records or students who may have experienced summer learning loss) and then again around the middle of the year (to check for changes and ensure students are progressing as expected). Some add another assessment after the first quarter or trimester (to make sure the year is off to a good start or to get better projections of future achievement), after the second trimester or third quarter (to ensure students are progressing as expected), and/or near the end of the school year (to provide a complete picture of learning over the year and a comparison point for the following school year).

Some will also assess a specific subset of students more frequently. However, many times these assessments move from answering “discover” questions to answering “monitor” questions.

Assessing to monitor ongoing learning

As the school year progresses, you may have questions about what and how your students are learning. This brings us to our second category of questions, the “monitor” questions, where you’re primarily looking to understand how students are progressing, if the instruction provided is working for them, or if changes need to be made. Whereas discover questions are more focused on the student before a new phase of learning beings, monitor questions are more focused on the student’s learning during the current phase of learning.

Monitor questions include:

- How is the student responding to core instruction? Is it working?

- How is the student responding to supplemental intervention? Is it working?

- Is she progressing as expected?

- Is she on track to meet her learning goals?

- How do I help her reach those goals?

- Is she experiencing typical, accelerated, or slowed growth?

- How does she compare to her peers?

- Is she learning the new skills being taught?

- Is she retaining previously taught skills?

- Which skills is she ready to learn next?

- Does she need additional instruction or practice?

- Does she need special support, scaffolding, or enrichment?

- Should she stay in her current instructional group or move to a different one?

There are several approaches that can be used to address monitor questions. Perhaps the two most common are progress monitoring and formative assessment. Note that progress monitoring and formative assessment are not assessment types in and of themselves. Instead, they describe processes that use assessment as part of an overall approach to monitoring student learning and shaping instruction.

As with discover questions, how often you need answers to monitor questions will help decide how often to assess students. Once again, if you’re not asking questions or if you’re not able to act on the answers, reconsider whether your limited time is best spent assessing students. Don’t arbitrarily assess students just because a certain amount of time has passed. Depending on the rhythm of your instruction and how quickly students seem to grasp new skills, your formal assessment schedule may not be a regular one—perhaps you’ll assess one week, not assess for six, then assess every other week for a month.

Similarly, if you only have questions about specific students (perhaps those identified as “at risk” or “on watch” by your universal screener or those currently in intervention), you may choose to only assess those students instead of the whole group. Alternately, you could assess all students on a semi-regular basis and then choose to assess identified students on a more frequent basis. In all cases, the information gleaned from formative assessment may be very helpful in deciding which students should take formal assessments and how often they should take them.

For formal assessments that are not part of instruction, time is also a critical factor to consider both when choosing an assessment tool and when deciding how frequently to use that tool. Consider an intervention model where students have 2.5 hours of intervention time per week. If your formal assessment takes one hour, using it biweekly means losing 20% of your intervention’s instructional time! Although you may want fresh insights every few weeks, you might decide the time sacrifice is too great and assess only once per month. Alternately, if your assessment tool takes only 20 minutes, you could assess every two or three weeks and lose very little instructional time. In short, consider assessment length when making timing and frequency decisions.

(Be sure to read our previous post about factors that affect assessment length, reliability, and validity.)

Although discover and monitor frequently overlap—the assessment you use to answer your discover questions may be the same one you use to answer your monitor questions—they tend to diverge quite a bit from our last category.

Assessing to verify completed learning

When you hear “summative assessment,” your first thought may be the large, end-of-year or end-of-course state tests that are required in many grades. However, these are not the only summative assessments in education. Final projects, term papers, end-of-unit tests, and even weekly spelling tests can be examples of summative tests!

Summative assessments provide the answers to our last category of questions, the “verify” questions. When a phase of learning has ended—such as a school year, course, or unit—educators often find it helpful to confirm what students have and haven’t learned. In some cases, this can help educators judge the effectiveness of their curriculum and decide if they need to make changes. In other cases, whether or not a student advances to the next phase of learning (such as the next course in a series or next grade) may be decided by a summative exam. At the state or even national level, summative assessments like the SAT can be helpful for seeing larger trends in education and evaluating the overall health of the education system.

- Which skills and standards has this student mastered?

- Did he understand the materials and content taught over the last learning period?

- Did he gain the skills and knowledge needed to meet state standards?

- What are his strengths, relative to the standards?

- What are his weaknesses, relative to the standards?

- How much did the student grow over this phase of learning?

- Is the student ready to progress to the next stage of learning?

- Did he reach his learning goals?

- How does he compare to his peers?

- How does my group of students, as a whole, compare to state or national norms?

- Did enough students master required standards?

- How effective are our core instructional and supplemental intervention services?

- Are there patterns of weakness among students that indicate a change in curriculum or supplemental program may be needed?

Of all the assessments types, deciding when to schedule summative assessments may be the easiest. In many cases, your state or district has already determined the frequency and timing for you. For the summative assessments that you schedule, ask yourself two questions. First, “Is this phase of learning complete?” If it is, then ask, “Do I need an overall measure of learning for this phase of learning?” If both answers are yes, then you may want to administer a summative assessment. If the first answer is no, you may want to delay your summative assessment until the phase of learning is done. If the second answer is no, you may choose to skip a summative assessment entirely—not all phases of learning need to be verified by a summative assessment.

Finding the balance between assessing and learning

Every time you set aside time for assessment, the time available for instruction shrinks. However, the insights provided by assessments can be critical for improving teaching and learning. Instruction without assessment can sometimes be like driving with a blindfold on—you might not know you’ve gone off course until it’s too late.

The key is finding the right balance between them. To help find that balance, keep these key questions in your mind whenever you think about assessing students:

- Do I have a specific question in mind that this assessment will help answer?

- Will those answers help me improve teaching and learning—is there a high-quality learning progression that helps the assessment connect with my instruction and curriculum?

- Do I have time to meet with the team and make plans based on the assessment data?

- Will I be able to make changes to instruction or content based on the assessment?

- Is assessment the best use of this time—or would it be better to dedicate it to instruction or practice?

- Could a shorter assessment answer my questions in less time—and thus preserve more time for teaching and learning?

The truth is that no one knows your students like you do. Only you can determine which assessment is best for your needs. Only you can decide the right timing and frequency for that assessment. Only you can find the right balance. Hopefully the questions and insights we’ve provided over this blog series will help you find your best assessment and learning progression as well as decide when and how often to best use those resources.

Sources

Black, P., Wilson, M., & Yao, S. (2011). Road maps for learning: A guide to the navigation of learning progressions. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives, 9, 71-123.

Center on Response to Intervention (n.d.) Progress monitoring. Retrieved from: https://www.rti4success.org/essential-components-rti/progress-monitoring

Center on Response to Intervention. (n.d.) Universal screening. Retrieved from: https://rti4success.org/essential-components-rti/universal-screening

Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). (2012). Distinguishing formative assessment from other educational assessment labels. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from: https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mde/CCSSO_Assessment__Labels_Paper_ada_601108_7.pdf

Fuchs, L.S. (n.d.) Progress monitoring within a multi-level prevention system. RTI Action Network. Retrieved from: http://www.rtinetwork.org/essential/assessment/progress/mutlilevelprevention

Great Schools Partnership. (n.d.) The glossary of education reform. Retrieved from: https://www.edglossary.org/

Herman, J. L., Osmundson, E., & Dietel, R. (2010). Benchmark assessment for improved learning: An AACC policy brief. Los Angeles, CA: University of California.

Lahey, J. (2014, January 21). Students should be tested more, not less. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/01/students-should-be-tested-more-not-less/283195/

Lazarin, M. (2014). Testing overload in America’s schools. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Paul, A. M. (2015, August 1). Researchers find that frequent tests can boost learning. Scientific American. Retrieved from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/researchers-find-that-frequent-tests-can-boost-learning/

Renaissance Learning. (2013). The research foundation for Star Assessments: The science of star. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.

Salvia, J., Ysseldyke, J. E., & Witmer, S. (2016). Assessment in special and inclusive education. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Stecker, P. M., Lembke, E. S., & Foegen, A. (2008). Using progress-monitoring data to improve instructional decision making. Preventing School Failure, 52(2), 48-58.

The Center on Standards & Assessment Implementation. (n.d.) Overview of major assessment types in standards-based instruction. Retrieved from: http://www.csai-online.org/sites/default/files/resources/6257/CSAI_AssessmentTypes.pdf

Wilson, M. (2018). Making measurement important for education: The crucial role of classroom assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 37(1), 5-20.