January 30, 2018

This is the third entry in the Education Leader’s Guide to Reading Growth, a 7-part series about the critical importance of high-quality reading practice when it comes to reading achievement, written specially for today’s education leaders.

Your students need more reading practice. Reading practice doesn’t just help struggling readers get on track for success; it can help all students—from all walks of life—accelerate reading gains and improve performance.

However, educators don’t have infinite time: There are only six or seven precious hours in a typical American school day. Given how much needs to be accomplished in this narrow window, it can be hard to ask teachers and students to stuff much more into their already-packed schedules.

That’s why it’s so essential to get the most out of every minute of reading practice. In this post, we examine three different elements—or “growth factors”—that help contribute to high-quality reading practice. Note this isn’t an exhaustive list of all the variables that may influence the effectiveness of reading practice (for example, the critical element of instruction is not covered), but rather a starting point to help guide your efforts around practice in the right direction.

Growth factor: The Zone of Proximal Development

The first factor for powering growth through reading practice that we’ll examine is the Zone of Proximal Development, or ZPD.

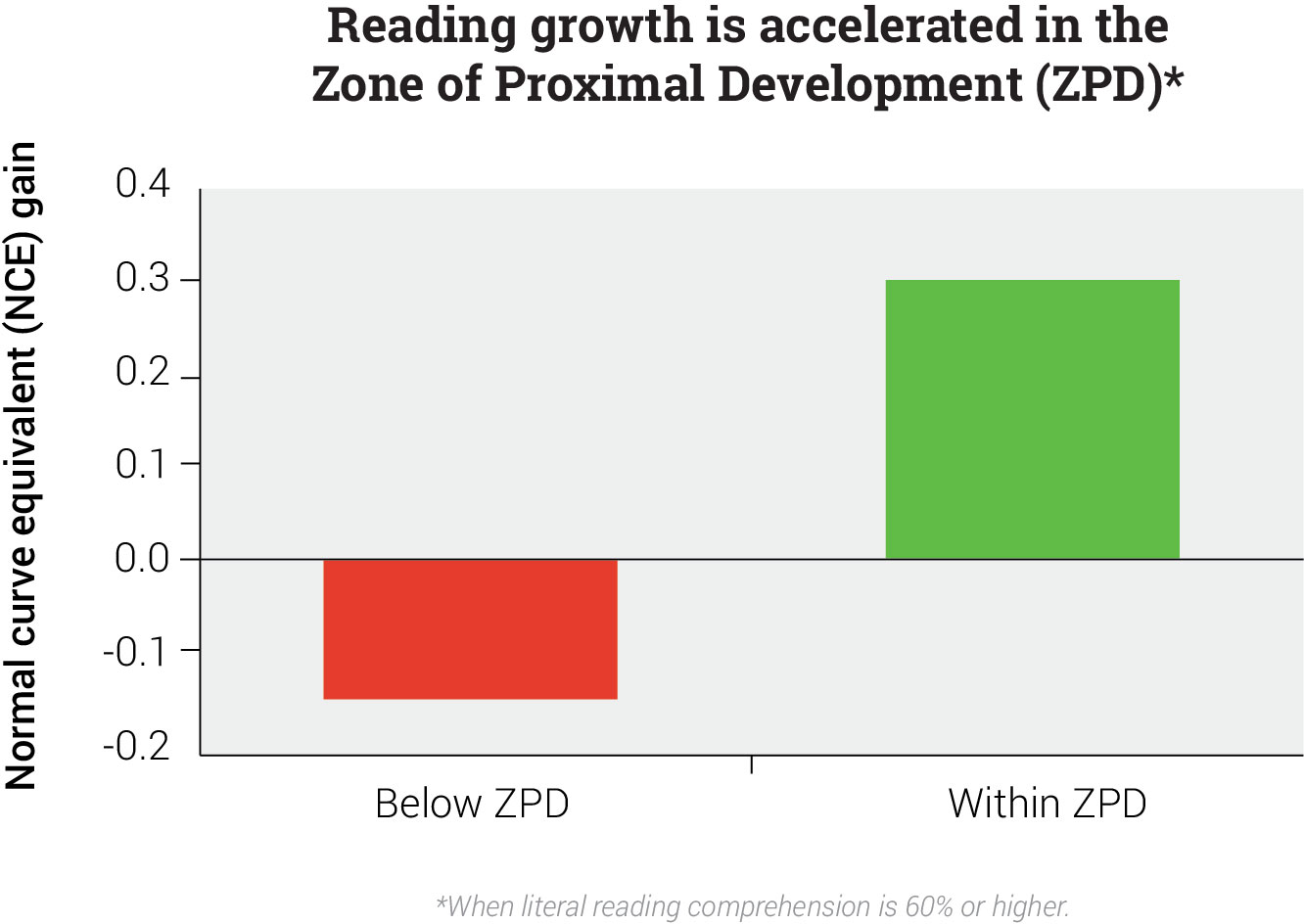

A study of more than 2.2 million students showed that students achieved accelerated reading gains—that is, grew at a faster rate than the national average—when they read within their ZPD, but did not when they read below their ZPD.1 This is only looking at students who averaged 60% or better on literal comprehension quizzes, as scores below 60% may indicate that a student did not actually read the book, did not put effort into understanding the book, or did not have the reading skills, background knowledge, or vocabulary needed to comprehend the book’s topic. (In our next post, we’ll examine the role of comprehension in far greater depth.)

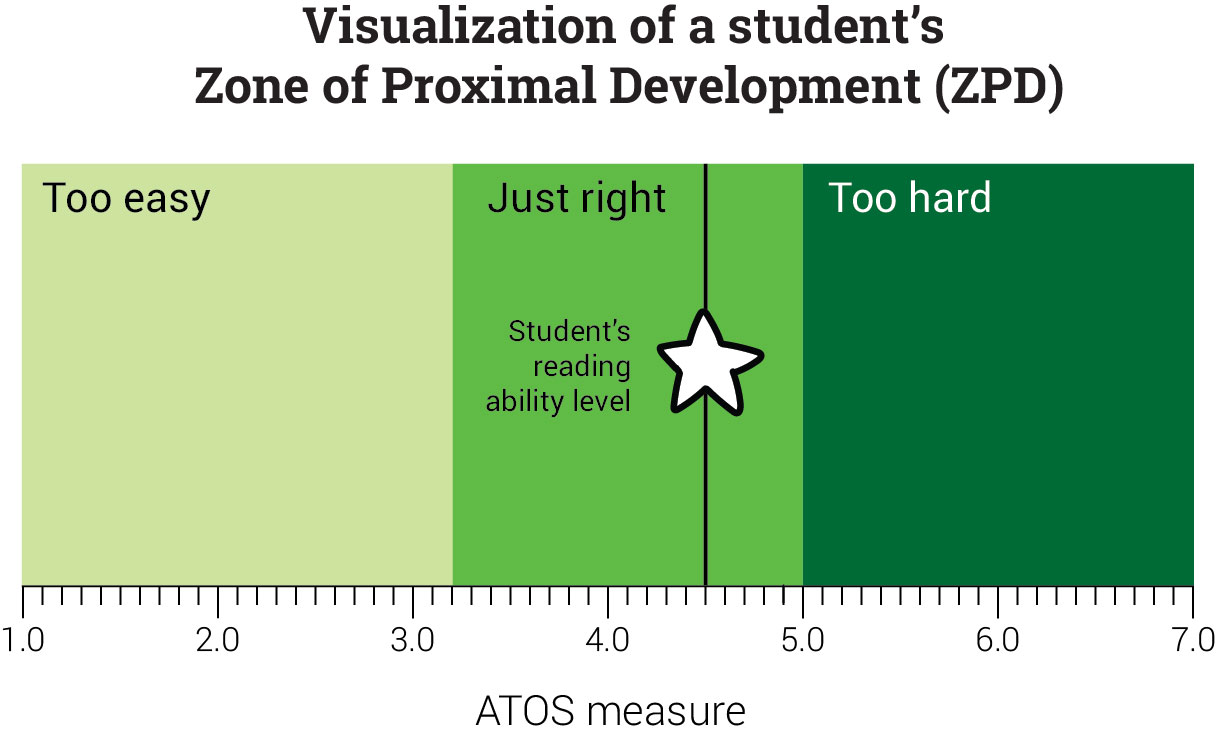

So what is ZPD? Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky first introduced the concept in the late 1920s. In general terms, it describes the range between what a student is able to do independently, without assistance, and what they are unable to do, even with assistance. Tasks that fall between these points—activities that a learner can accomplish with scaffolding, guidance, or collaboration—are within a student’s ZPD. A key element of ZPD is that it is specific to each learner and will change as that learner grows and refines their skills.

When it comes to reading practice, a different definition of ZPD often emerges. Frequently, ZPD is used to describe the range of text complexity that a student can read independently but not effortlessly—some educators may also call this a student’s “instructional level” or “independent reading level.” Reading materials in a student’s ZPD should offer just enough challenge to help them build stronger reading skills, but not so much that they become frustrated and discouraged from further reading. Depending on the reading scale and formula used, ZPD ranges often start just below a student’s measured reading ability and then extend to texts that are just above their ability level.

While ZPD represents an optimal range of reading challenge for a given student, it is imperative to note that not everything a student reads must be within their ZPD. Moreover, children should not be limited to only those reading materials within their ZPD.

Plenty of reading materials below a student’s ZPD can contribute to their socioemotional learning; expand their academic vocabularies; build knowledge in science, social studies, and other content areas; and grow their love of reading. These are all important reading outcomes, even if they may not necessarily contribute to accelerating reading gains. As long as a student is reading plenty of materials within their ZPD and hitting growth goals, there is no reason to prevent them from reading some below-ZPD materials.

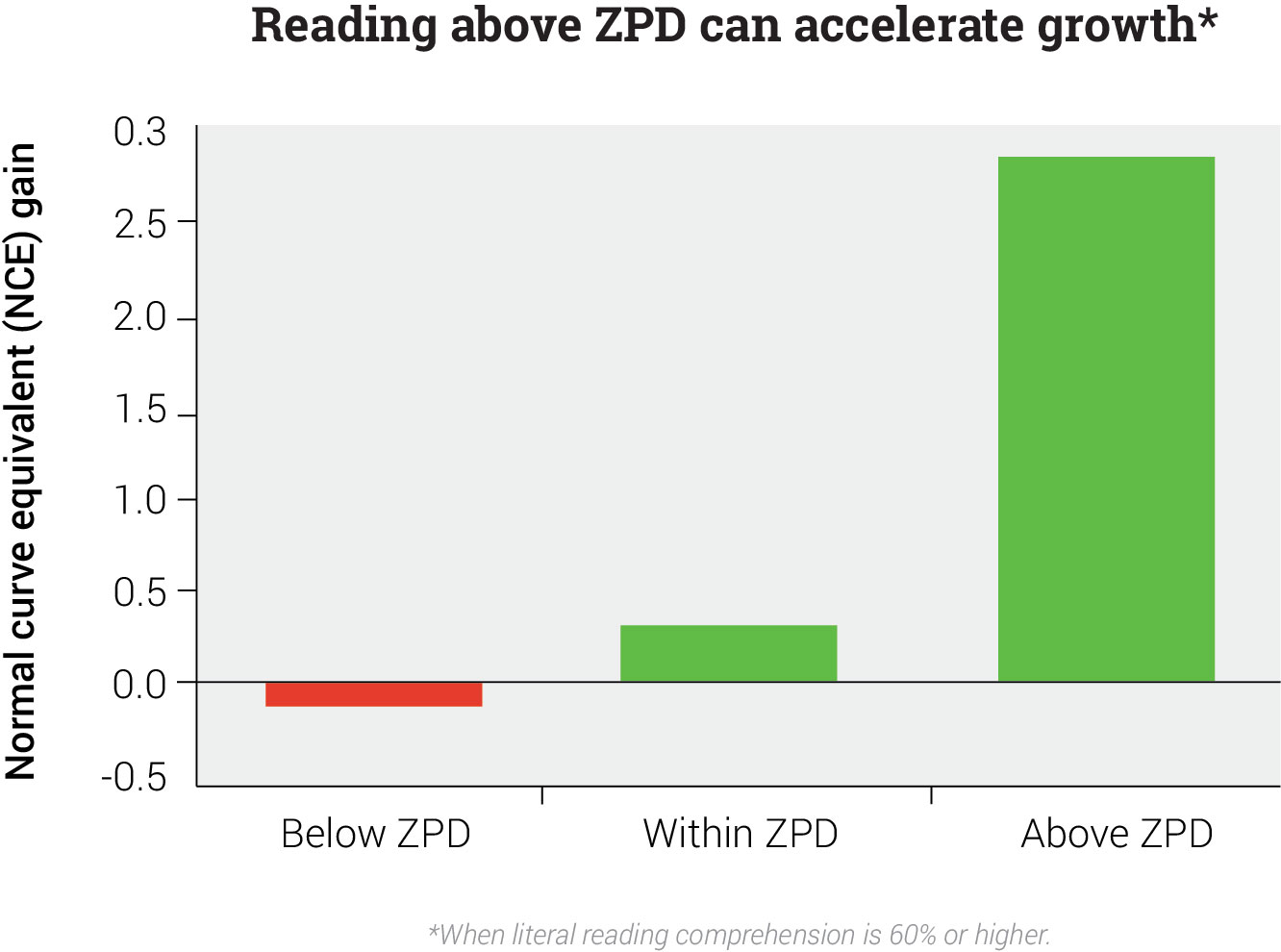

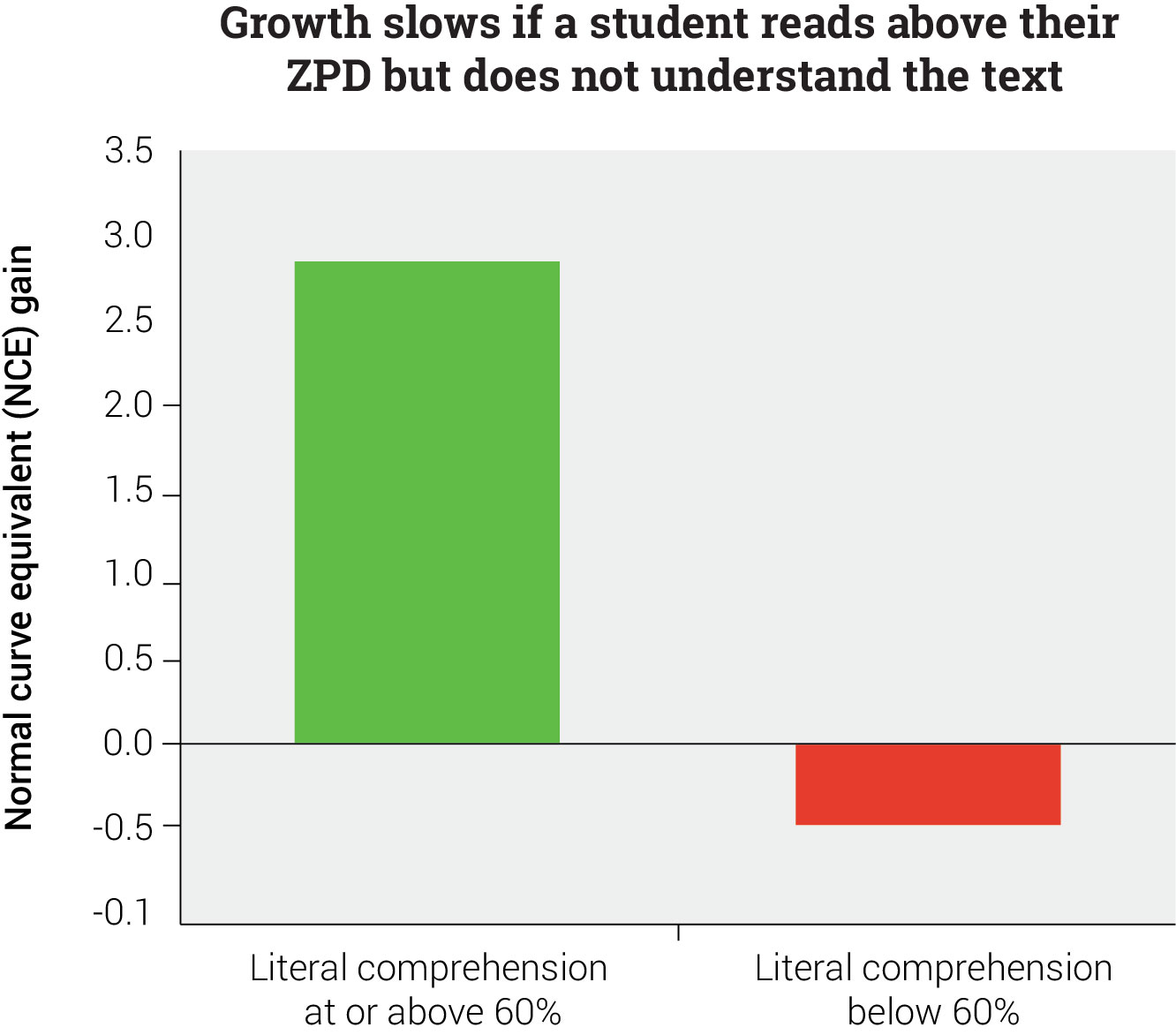

At the other end of the scale, there can be great benefit to exposing children to materials that are above their ZPD. When children have the skills, scaffolding, and support needed to keep literal comprehension above 60%, above-ZPD reading is associated with significant positive reading gains. Examples of scaffolding may include teaching content and concepts prior to reading, previewing vocabulary, listening to the book read aloud, or reading with a more skilled partner.

However, it should be noted that merely giving students harder books will not automatically accelerate reading gains—and could actually slow progress if they cannot understand them. To maximize gains, it is better to give students a book within their ZPD that they can understand than a book above their ZPD that they cannot.

In addition to slowing growth, pushing students to read above their ZPD may also decrease motivation. One study published in the Journal of Educational Research noted that students were less motivated to read and exhibited fewer on-task behaviors when they were asked to read materials far above their skill level, even when paired with more proficient readers for support.2 Although these students saw reading level gains, further analysis found no statistically significant difference in gains between the students reading far above their instructional level and those reading at their instructional level.

In summary, the rules of thumb might be:

- Encourage lots and lots of within-ZPD reading to ensure reading gains.

- Encourage below-ZPD reading if the content will help a student grow in areas outside of the language arts or will increase motivation.

- Encourage above-ZPD reading if the student has both the motivation and the support/scaffolding needed to meaningfully engage with the text.

Growth factor: Quality and diversity of reading materials

An analysis of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores looked at the reading habits of more than 174,000 students across 32 countries, including nearly 4,000 in the United States.3 The study found that students generally fell into one of four categories or “reader profiles”:

- “Least diversified readers,” who only read one type of content with any real frequency (multiple times per month);

- “Moderately diversified readers,” who read two types of content (typically magazines and newspapers) with frequency and occasionally read other content types;

- “Diversified readers in short texts,” who frequently read short-form content (such as comics, magazines, and newspapers) and occasionally read long-form content; and

- “Diversified readers in long and complex texts,” who frequently read both long-form and short-form content.

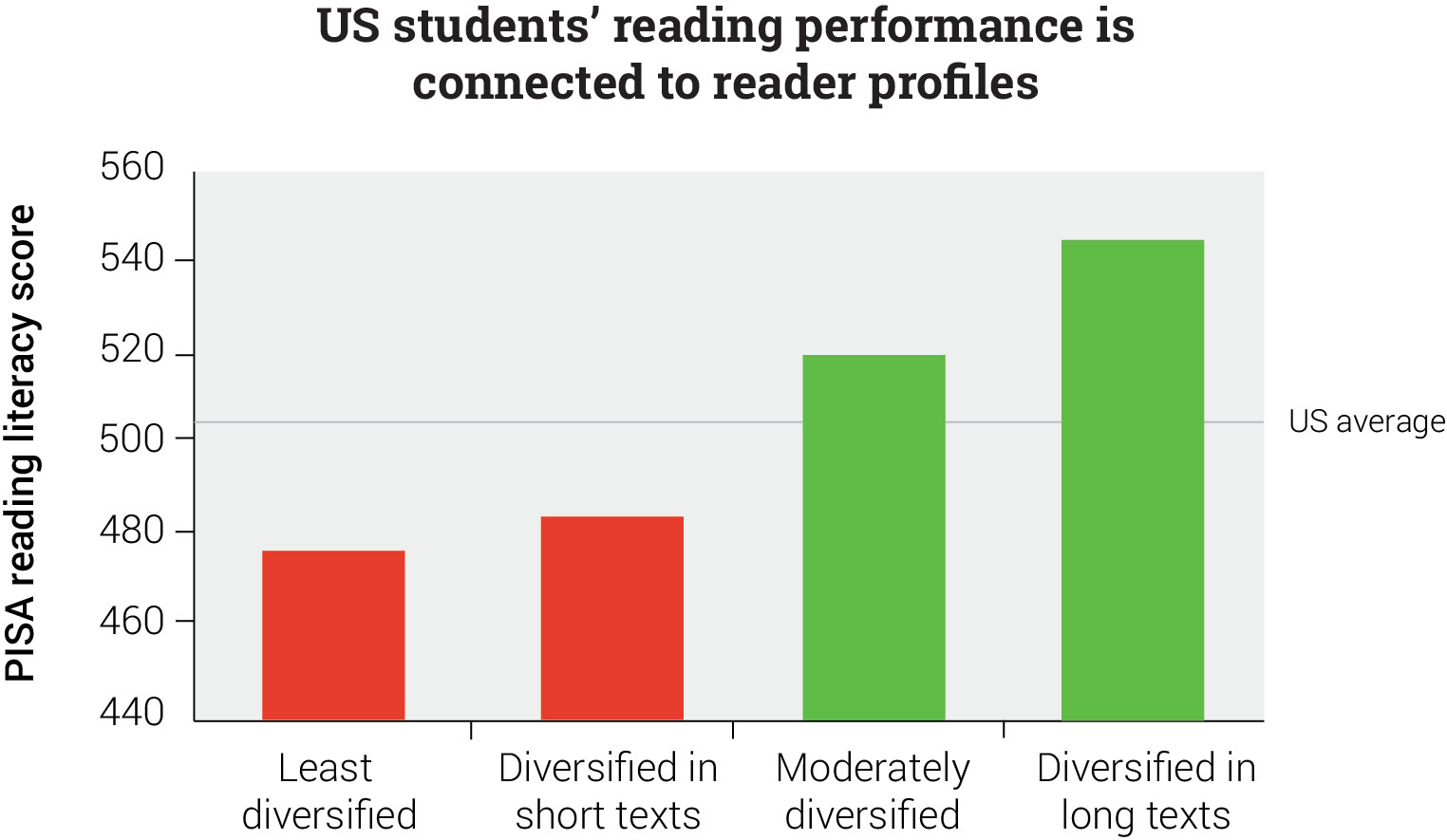

Within the US, two groups had average scores below both the national and international average, and two groups scored well above both averages. It should be no surprise that the top-scoring group was “diversified readers in long and complex texts” and the bottom-scoring group was “least diversified readers.” However, what may be surprising is that “diversified readers in short texts” performed only slightly better than “least diversified readers.” “Moderately diversified readers” scored considerably better than “short texts,” but not nearly as well as “long texts.”

It’s not just reading a lot that’s connected to high scores—it’s reading lots of different texts, too. Based on this data, a steady diet of only short-form content such as newspaper articles, magazine features, comic books, short stories, or book excerpts does not appear to help students reach the highest levels of reading achievement. They need books. Frequent reading of fiction and nonfiction books, combined with frequent or occasional reading of shorter texts, appears to be a key part of the overall recipe for reading success.

Students need books. Frequent reading of fiction and nonfiction books, combined with frequent or occasional reading of shorter texts, appears to be a key part of the overall recipe for reading success.

Why do long, complex texts have such an impact on achievement? Although definitive data is not available, it may be that these longer texts not only allow students to build general background knowledge, but to also build deeper background knowledge—to explore a single topic or concept more extensively for richer understanding. They may also grow a student’s reading stamina, i.e., their ability to focus on independent reading for longer periods of time without being distracted or disengaged from the task.

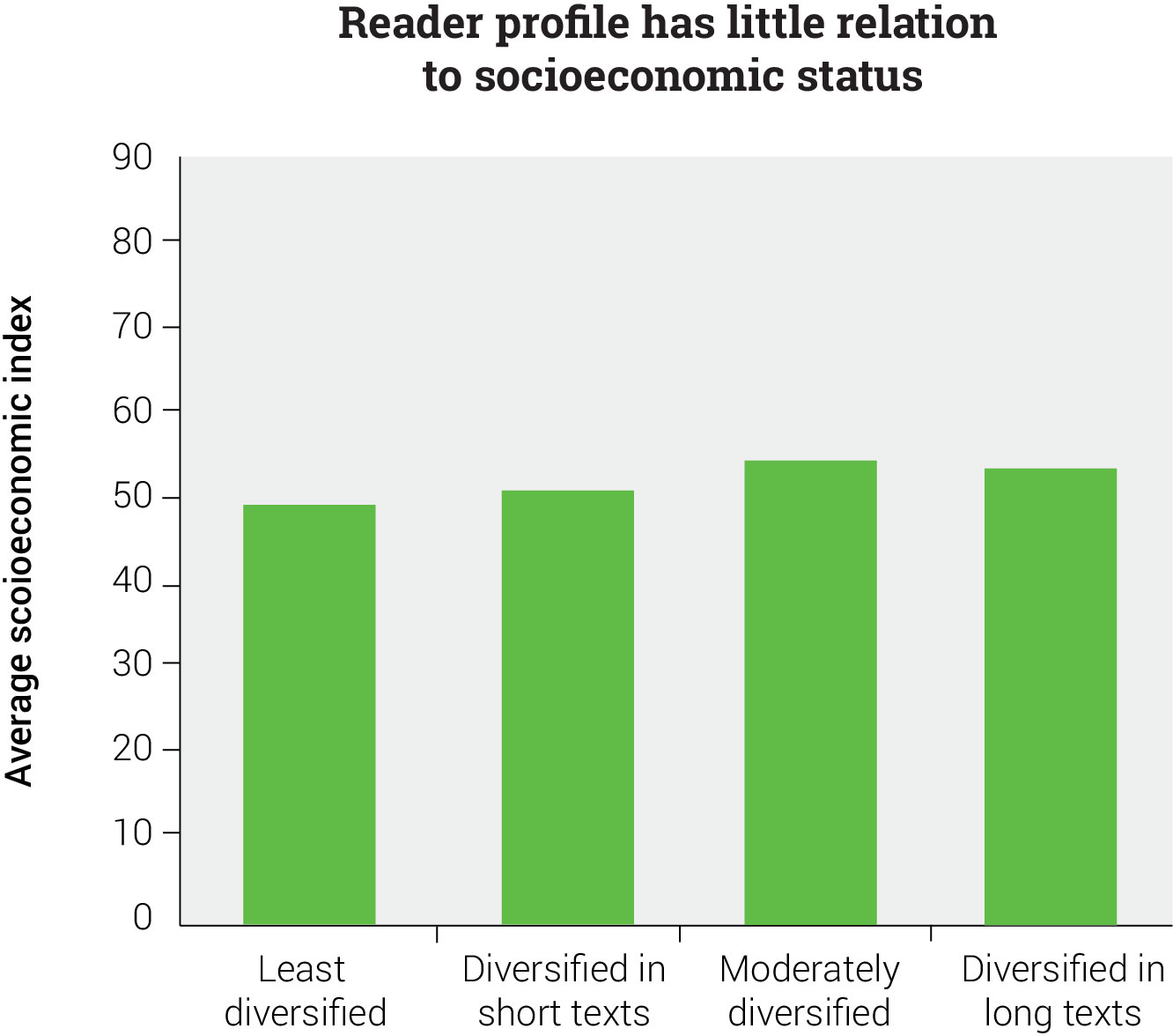

Note that socioeconomic status appeared to play only a small role in which type of reader a student was. The average socioeconomic differences between the four reader profiles were found to be small in every country studied. Within the US, the “moderately diversified” group had highest mean index for socioeconomic status (54.7 on a 0–90 scale), followed closely by “long texts” (54.0), then “short texts” (50.8), and “least diversified” (49.4).

This matches the data explored in the last post, where a student’s level of reading engagement was a stronger predictor of their reading performance than their socioeconomic status.

What did seem to matter, however, was a child’s access to reading material at home—specifically books. Students in the “long texts” group had the highest access to books, while students in the “least diversified” group had the lowest access to books.

Access matters: Students who have access to books outside of school are more likely to be diversified readers who frequently read long and complex texts.

What does this mean for schools? While educators can’t control students’ home environments, they can boost equity of access by investing in school and classroom libraries, subscribing to digital services that offer rich catalogs of eBooks and other reading materials, and encouraging students to bring home books, eReaders, or other digital devices for reading. Reading options can be further enriched with kid-friendly newspapers or magazines (digital or print), but make sure all students have a way to read books and/or eBooks at home.

Growth factor: Student effort

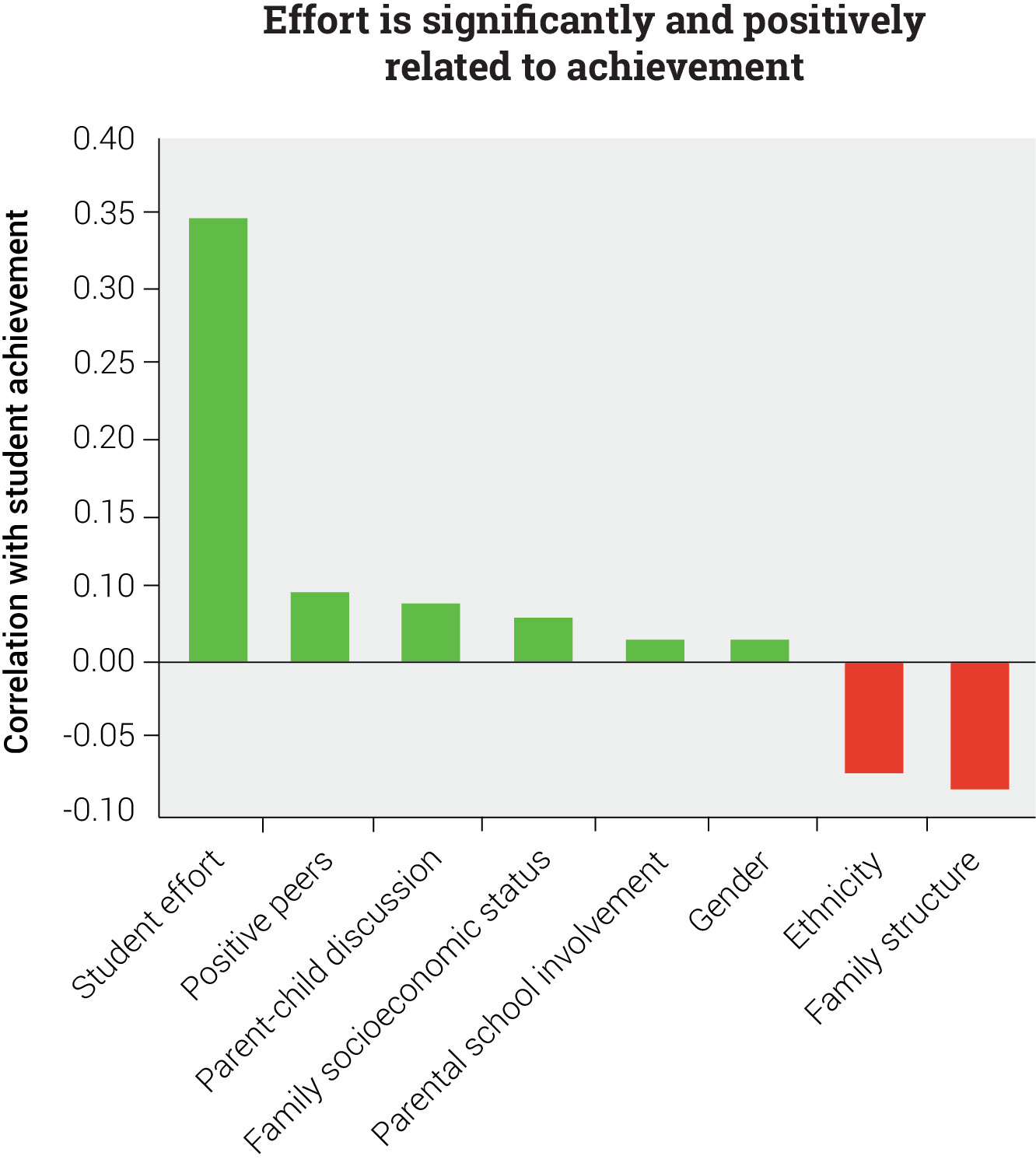

A study of 12,000 students across 715 high schools found that student effort was significantly and positively related to a student’s achievement as measured by their GPA.4

A multilevel regression analysis further found that student effort was a better predictor of achievement than any other individual-level variable examined, including gender, family structure, ethnicity, and family socioeconomic status, as well as behavioral factors such as associating with peers who encouraged positive education-oriented behaviors (positive peers), discussing school with parents or guardians (parent-child discussion), and having parents or guardians who were involved in school activities (parental school involvement).

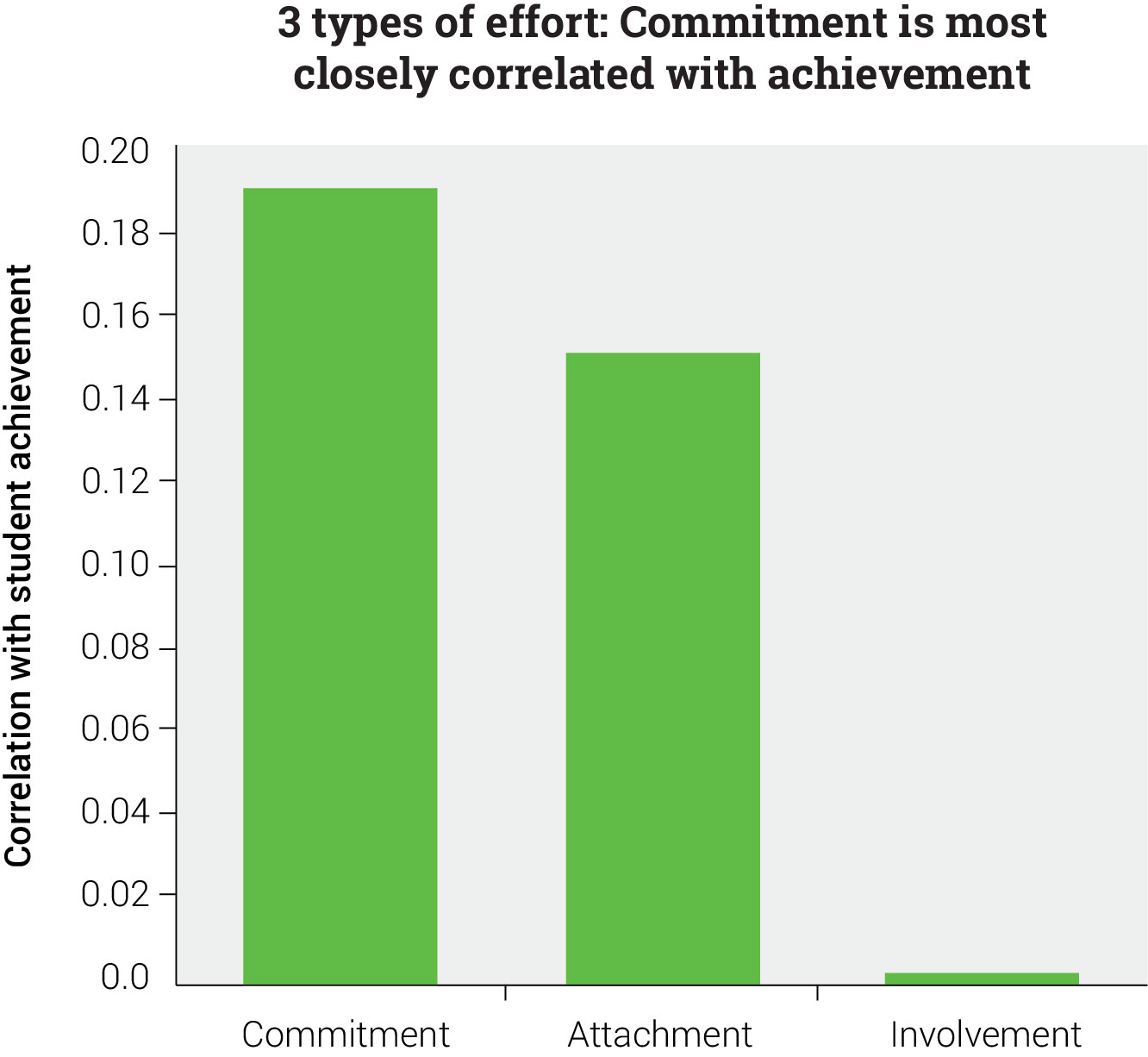

When examining student effort more closely, a specific type of effort—commitment—had the strongest relationship with achievement. This describes a student’s commitment to their education: taking an interest in their schoolwork, trying to stay on task in class, working hard to achieve good grades, and understanding the role of education in post-school success (i.e., getting a job).

Attachment, the extent to which students care about and have positive feelings for school, was the next highest. Involvement, a student’s participation in extracurricular activities (e.g., band or sports), did not have a significant correlation with achievement.

It should be noted that commitment and attachment, as individual factors, each had a greater correlation with achievement (0.19 and 0.15 correspondingly) than the next-highest factor (positive peers at 0.09). Simply put, effort seems to matter a lot when it comes to achievement.

And effort appears to have a huge impact for all different types of students. A separate analysis of nearly 7,000 high school students across four different tracks—honors/advanced, academic, general (reference), and vocational/other—found that effort had significant, positive effects on achievement in every track. The results further indicated that the effects of effort on learning are the same for all students, regardless of their track.5

Another important finding was that, while prior effort did have an effect on current achievement—learning is cumulative, after all—the effect was much smaller than that of current effort. The authors concluded that students who try harder learn more, regardless of how much effort they exerted in previous years. In other words, it’s never too late for students to see the benefits of trying harder, even if they didn’t do so in the past.

It’s never too late for students to see the benefits of trying harder, even if they didn’t do so in the past.

In the context of reading practice, we suggest that students who have not previously put much time or effort into reading could still reap notable benefits by starting today—especially if they start applying themselves to a wide variety of reading materials within their ZPD. The combination of ZPD, diversified texts, and effort all help students to get more out of every minute they spend reading, with the potential to fuel greater gains and higher achievement.

We’ve now set our students up for accelerated reading gains. We’ve set aside at least 15 minutes every day for reading practice. We’re encouraging students to read books that are in their zone of proximal development. We’ve given students access to a wide range of texts, including books, and we’re making sure students can use those texts at home for after-school reading. We’ve told students how important effort is and are motivating them to try their best when reading.

(For more information on motivation and its impact on reading achievement, see the fifth entry in this series.)

But how do we know growth is actually happening without waiting for midyear or end-of-year testing? Obviously, nonstop testing is not an option. Thankfully, there is a way to monitor high-quality reading practice—a reliable indicator of growth that’s quick and easy for both students and educators—and it’s the topic of our next blog post.

References

1 Renaissance Learning. (2015). The research foundation for Accelerated Reader 360. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.

2 Morgan, A., Wilcox, B. R., & Eldredge, J. L. (2000). Effect of difficulty levels on second-grade delayed readers using dyad reading. Journal of Educational Research, 94, 113-119.

3 Kirsch, I., de Jong, J., Lafontaine, D., McQueen, J., Mendelovits, J., & Monseur, C. (2002). Reading for change: Performance and engagement across countries: Results from PISA 2000. Paris, France: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

4 Steward, E. B. (2008). School structural characteristics, student effort, peer associations, and parental involvement: The influence of school- and individual-level factors on academic achievement. Education and Urban Society, 179(2), 179-204.

5 Carbonaro, W. (2005). Tracking, students’ effort, and academic achievement. Sociology of Education, (78)1, 27-49.