January 8, 2015

As I reflect back on almost 40 years in the field of education, I note how fitting it is that the job from which I retire is with Renaissance Learning, as these 40 years can be viewed as an ongoing “renaissance” in the field of education. In my view, the changes in education in this span of time are deep enough to be considered a rebirth, yet educational progress continues to be weighed down by the underlying issue of poverty in the US. Where does this leave us? Can true reform take hold and improve outcomes for our children when societal factors threaten that well-intended work?

In some ways, progress is undeniable: Forty years ago children with disabilities were not only not in school, many were specifically excluded. And today, we educate almost 7 million students with disabilities in the public schools. The same could be said of the use of technology. Forty years ago we used typewriters, and just one computer filled a room. Today we carry a mini-computer in our pocket, and it connects us instantly to almost anywhere in the world and with any piece of information we desire or need to know.

Yet, with all our advancement and today’s emphasis on college- and career-readiness standards, rigorous assessments, personalized learning, parental engagement, and data literacy, it’s worth asking whether recent efforts really represent major shifts in thinking compared to 40 years ago. With so much resistance to current reforms across the US, it’s a good time to look at how our goals for reform stack up to those of the past:

- In 1974, the US public wanted the most productive workers in the world. Today, the public wants this and more, with a focus on the need for even more highly trained and educated workers with a focus on STEM.

- In 1974, civil rights were preeminent as the public wanted to remove inequality and provide equal access to education for all. Today, the public continues to cite civil rights and wants educational options—school choice—to ensure every child has a fair opportunity to receive an excellent education.

- In 1974, the public wanted equitable funding based on the needs of the students. Today, the public wants more funding that is both based on need as well as being competitive.

- In 1974, the public wanted the most highly qualified teachers. Today, the public wants the most highly effective teachers based partly on student academic performance.

- In 1974, the public wanted to overcome the effects of poverty to lessen the achievement gap. Today, the public wants to address this gap via accountability for all students—making tests count and ensuring 100 percent of all students are proficient or above.

Have we changed that much? The underlying issues of education reform seem consistent, even if the ideas for what’s needed to get us there have evolved.

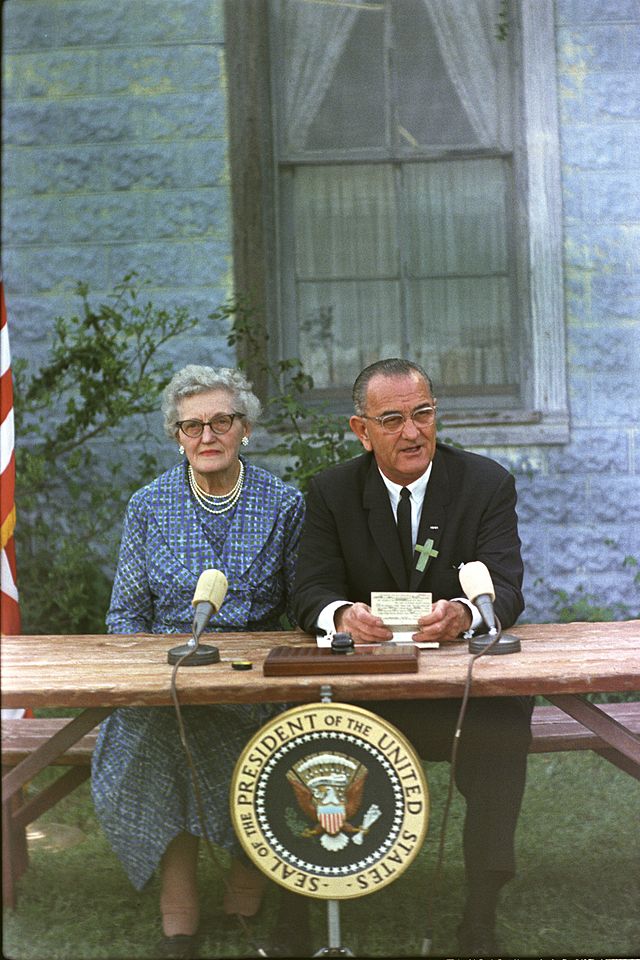

Photographer: Frank Wolfe Lyndon B. Johnson at the ESEA signing ceremony in 1965, seated at a table with his childhood teacher, Ms. Kate Deadrich Loney.

Perhaps the greater question weighing on our minds is, how are we doing today? Again, awareness of the past is crucial to arriving at the right answer. Back in 1965, when the “War on Poverty” was launched, for the first time the federal government became part of the solution to ensuring equality and enhancing national productivity. This was the beginning of a focus on children who were part of low-income families, who needed to be ensured that adequate educational programs were available for all. Additionally, for the first time, the federal government provided financial assistance to local districts with high concentrations of children from low-income families. Most agree that this was needed. And more of these initiatives followed, into every decade since the 1960s.

Looking back, the US has made a tremendous effort to ensure equity for all. How successful has this been? Some say we’ve fallen short. Some say, not so fast.

The trend today is to conclude that the US is not doing a good job in terms of education, and in fact, many say we’re losing ground. Scores on international exams have often been cited as evidence that education in the US is getting worse, not better. Results from the most recent PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) showed that US students are somewhere in the middle of the pack, and this has been offered as “proof” that our kids are being prepared to become second-class citizens. Yet at the same time, the World Economic Forum and the Institute for Management Development once again ranked the US number 1 in overall competitiveness, a rather dubious honor for a country with so-called low-performing schools. (The Global Competitiveness Report and an interactive data platform are available here.)

Yet, as Walt Gardner put it, saying we’re worse off now is simply not true: “So much anger aimed at public schools today is based on the assumption that they were far better in the past.” He goes on to say, “The trouble, however, is that there never was an educational Eden in this country. In fact, ever since public schools have existed here, they’ve been the subject of complaints that sound very much like those heard today.”

Jay Mathews, from the Brookings Institute, shared that US students’ performance on PISA has been flat to slightly up since the test’s inception; scores on the TIMSS (Trends in Mathematics and Science Study) have improved since 1995 as well.

The bottom line is this: The role of public schools in the US is to assist every child in learning to the highest level possible. We all must accept responsibility for enhancing and improving student learning. We have some of the most productive workers in the world—some of the most thoughtful, innovative, and imaginative people today. This country has the most inventors and holds the most patents. What has made a difference in the US is that we have the freedom to do what works best and the ability to instill creativity, imagination, and innovation in every child’s mind.

One of the major backlashes we are contending with today is whether we have too much testing in the schools—and this is a real concern, likely the result of many tests not being instructionally relevant. That is, the purpose of summative measures is to tell us what a child can or cannot do at one point in time, whereas formative or interim assessments are purposefully and directly linked to instruction. (See our recent blog posts on this topic here and here.) We need to know how well a child has learned a concept or a skill or whether intervention is needed. Assessments are not necessarily negative, nor should they be viewed as judgmental. They are the very tools that lead to student achievement and success.

So what does all of this mean? Why does it appear that the voices in education are more divided than ever, when in reality they are raised in unison to demand what’s best for students? If we can agree that reform has occurred and continues to occur, and that our interests are aligned to what’s best for students, we can focus on the questions that continue to need to be addressed:

- Is dissatisfaction with our public schools new? Did the landmark A Nation at Risk report overrate the threat to our society and to our economy? Or is it that school performance plummets when the concentration of low-income students gets above a certain threshold?

- Do our low-income students score worse than other countries’ low-income students? Or do we simply have more low-income students?

- Are teachers feeling more pressure to improve their test scores? Have teachers had to dilute their creativity to teach to the test? Is the preparation of students for tests becoming enormously time-consuming?

- Does the public support the use of students’ standardized test scores to evaluate teachers?

- Do parents want their children to be exposed to more than a one-size fits-all approach in education?

- Why is there resistance to federal involvement in education? Is it because of the Tenth Amendment, which limits the powers of the federal government? Anti-centralization? Fiscal restraint? Party politics?

- What should the role of the federal government be? To stimulate action by targeting funds? To discover and make knowledge and information available? To provide services like technical assistance? To regulate and enforce? To give direction?

- What should students know and be able to do? And who should determine this? How should it be determined? What is an appropriate level of knowledge and skill?

These questions and others have been asked for at least the last forty years, yet it’s easy to lose sight of or sugarcoat the past. It serves us well to remember where we’ve been, what has been done in the name of educational reform and why. And we should use this lens focused on the past to help us reserve judgment about the factors affecting student outcomes and whether those outcomes are moving in the right direction. I am hopeful that each “new” idea in education holds the potential to benefit all students. Renaissance Learning’s mission is “to accelerate learning for all children and adults of all ability levels and ethnic and social backgrounds, worldwide.” The optimism in these words is supported by history—we are on a solid path to reform. What better goal could we have than to improve the lives of all children everywhere and to provide them with the education they need to thrive and grow in the 21st century?