June 12, 2020

Note: This is the fifth in a series of blogs on using your assessment data to address learning gaps during the 2020–2021 school year.

Last January (which now seems like a lifetime ago), state education leaders, researchers, and teachers gathered for a summit focused on evidence-based strategies for reading instruction. A grade 3 teacher was among the summit’s panelists. She explained that in her first year of teaching, she poured over her interim assessment data and was alarmed at what she found: “I could see that the students were not learning to read, but I didn’t know what to do.” With support from more experienced colleagues, however, she discovered what to do: Identify the most critical skills for learning to read, and focus daily instruction there.

As you reflect on the many unknowns around Back-to-School (BTS) 2020, you may feel as if you’re facing another “first year of teaching”—but with one key difference. This time, you know exactly what to do. Over the course of this blog series, you’ve focused on using the basics of assessment to inform teaching and learning. You’ve remained flexible in considering varied school-opening scenarios, and in establishing baselines for measuring proficiency and growth. You’ve considered both the academic and the social-emotional needs of students, teachers, and the wider community.

Your focus has been unwavering, which is no easy task, because focus is more than simply paying attention. It is a state of mind.

Understanding states of mind

As Sood (2013) points out, we operate in two states of mind—default and focus. Both states are critical to survival. In the default state, you are attuned to everything (e.g., breathing, maintaining heart rhythm, sitting upright) while ready to spring into action when focus is required. When your brain is in the focus state, it engages your “task-positive network” and “mutes the dialogue” of some tasks, so that you are fully immersed in the present experience. In this mode, you have clarity, you have direction, and you get things done.

At this point in planning for BTS 2020, most educators are operating in the default state and attending to everything. For example, school leaders, teachers, parents, and the community are evaluating multiple onsite scenarios to return to school, as well as a collection of hybrid/blended “brick to click” or “click to brick” models. Further, as educators analyze the impact of varied remote learning experiences, they seek to understand which learners thrived and which ones did not. Educationally speaking, we are operating in default mode and attending to everything (with immense efficiency), yet are prepared to spring into action when focus is required.

Two ends of a continuum

In addition to considering where learning happens, how each student thrives requires concentrated focus. As you determine where students are in the context of grade- or course-level placement, what they know, and what they’re ready to learn, you’ll also need to consider approaches to remediate learning that was disrupted by the pandemic. Decisions about teaching and learning find focus within two ends of a continuum: providing instruction at grade level at a slower pace, with attention to prerequisite skills, scaffolding, and tutoring; or, meeting learners where they are with targeted instruction to close skill gaps.

Star Assessments, along with your knowledge of your data and classroom dynamics, provide information and resources to bring to light focal points for student learning. In this blog, we explore scenarios and provide strategies for doing just this—in other words, for designing instruction that’s focused on the most critical skills for accelerating student learning.

How do you know which skills are most critical?

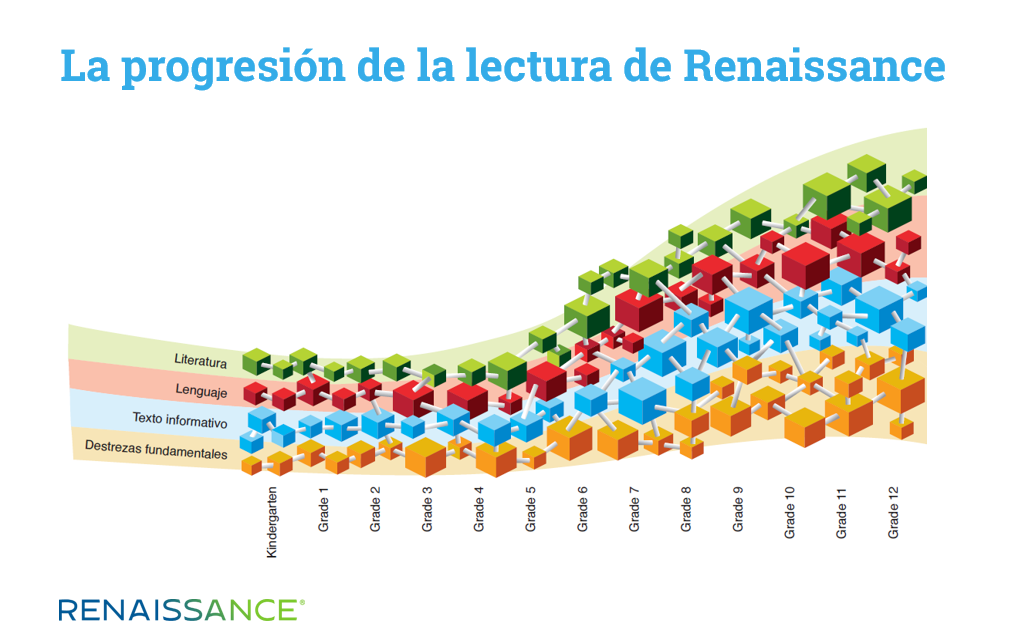

The “backbone” of Star Assessments is an empirically validated learning progression for both reading and math. Mosher (2011) describes the idea of a learning progression in this way: “Kids learn. They start out by knowing and being able to do little, and over time they know and can do more.” In other words, learning to perform specific tasks happens in a somewhat consistent pattern, over a somewhat predictable amount of time. Mosher expands his discussion of learning progressions from what children know and can do to how their thinking becomes more sophisticated as they respond to instruction and experience both in and out of school.

Renaissance has been working with learning progressions in reading and math for over a decade, creating progressions for each state, country, or locality in which we work. Our content experts take each state’s or country’s educational standards and break them down into discrete, teachable skills. Then, working in consultation with leading authorities in reading and math, we organize these skills in the most ideal teachable order, so educators can help students move along the pathway to greater mastery, as shown in the following graphic.

Using Focus Skills to accelerate learning

Learning progressions show the steps between standards—the focus of day-to-day learning.

—Margaret Heritage

During the process of translating educational standards into discrete skills, we were able to identify a subset of skills that are fundamental to students’ development at each grade level. We refer to these as Focus Skills™.

The Renaissance process for identifying Focus Skills is profiled by Kirkup et al. (2014), who state that these skills meet one or more of the following criteria:

- Are essential to the progression, involving concepts learners must master in order to move to the next step

- Support the development of other skills, serving as prerequisites for skills to come

- Reflect the emphasis of the curriculum

What about the non-Focus Skills? We recognize that acquiring any new skill impacts learning, but multiple studies have suggested that the typical grade-level list of standards represents more than can be taught in a single school year. To accelerate learning, we need to identify the most critical skills at each grade level, meaning those that drive the most student growth. As Fogarty, Kerns, and Pete (2017) note, “We have intuitively known that not all skills are created equal, but we often fail to consistently use that knowledge in our planning and prioritization.”

When you can easily identify the most critical skills, you know exactly where to focus instruction and resources to move students forward. Just as importantly, you also know the most critical skills from prior grade levels, which helps you to determine what to review and—when needed—what to set aside. The well-known Law of the Vital Few (also known as the Pareto Principle or the 80/20 Rule) is true for Focus Skills as well: 80 percent of the results come from 20 percent of “the knowledge acquired, or the skills developed, within a domain” (Lemov et al., 2012).

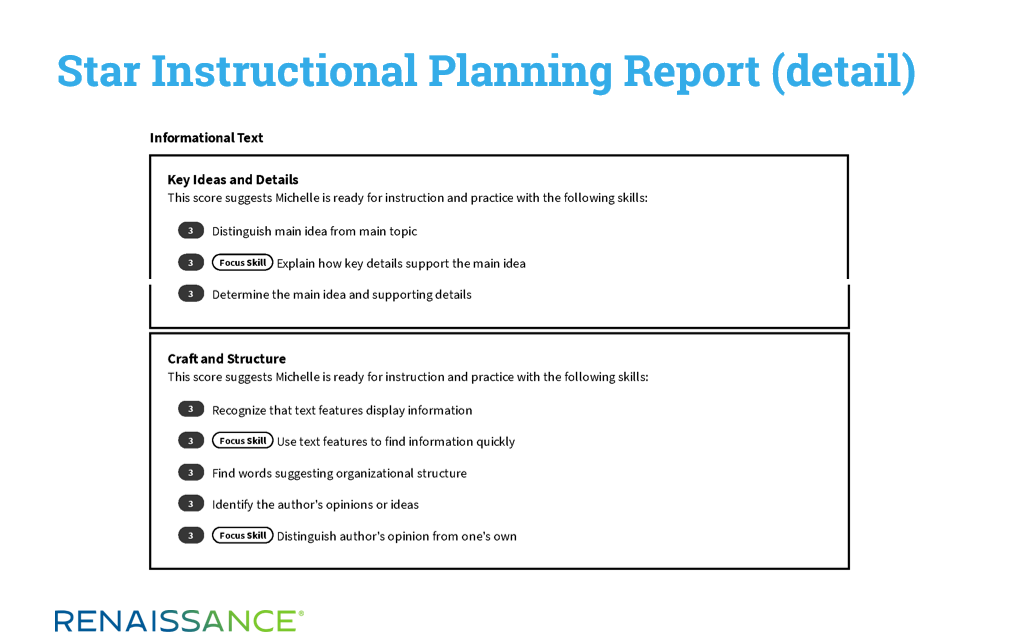

For BTS 2020, Focus Skills can become your “vital few,” with intense work on these skills producing the greatest returns in student learning. So, where can you see Renaissance Focus Skills? They’re highlighted on the Instructional Planning Report in Star Reading, Star Math, and Star Early Literacy. Teachers have the option of generating the Instructional Planning Report at the class level to identify the “vital few” for core instruction. Likewise, teachers can create instructional groups based on students’ Star data, and they can then run an Instructional Planning Report for each group. Finally, teachers may choose to run the Instructional Planning Report for individual students.

To see this process in action, let’s take the example of a grade 5 student named Michelle, who receives both grade-level instruction with scaffolding, and additional supportive instruction to address learning gaps. Michelle’s Star Reading score suggests the skills she’s ready to learn, which—in the state where she lives—are mostly at the grade 3 level. All of these skills are listed on Star’s Instructional Planning Report and are organized by domain, as shown below.

Note that in the Key Ideas and Details (Informational Text) domain, Michelle is ready to work on three skills. However, the report clearly identifies the Focus Skill—Explain how key details support the main idea—that is essential to Michelle’s growth. In fact, we need to accelerate Michelle’s growth substantially this school year, to help her meet grade 5 expectations. Concentrating on the Focus Skills will be an important step in accelerating her learning.

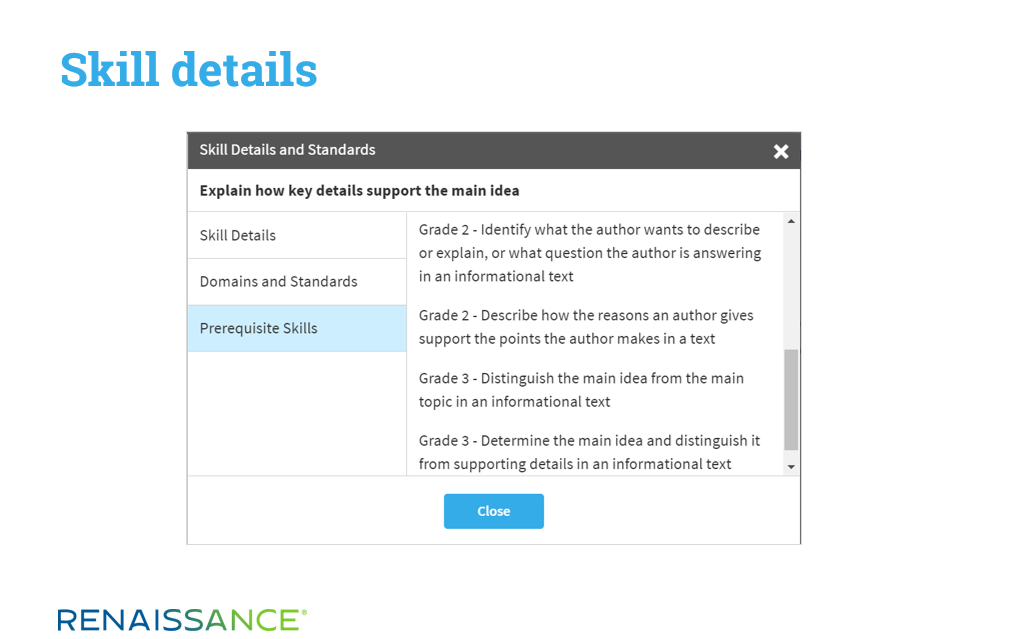

In addition to running the Instructional Planning Report, you can also see Focus Skills in the Renaissance Planner. The Planner enables you to view more detailed information about each skill, including related academic vocabulary, prerequisites, state standards alignment, and grade-level domain expectations.

Once you select a Focus Skill for a student, student group, or entire class, you can then use the Planner to access aligned resources to support instruction and practice, and to monitor student mastery. These resources include performance tasks and activities created by Renaissance, along with curated open educational resources (OERs) from Khan Academy, EngageNY, and other providers. Taken together, these resources help you to extend student engagement with Focus Skills beyond the classroom, and to support student learning wherever it occurs.

Where to find Focus Skills in Star Assessments

Closing COVID-19 learning gaps

Educators who use Star Assessments have multiple options for easily accessing Focus Skills. But given the urgency around reversing COVID-19-related learning loss, we’re making the full list of our Focus Skills available to all educators, parents, community members, and even students in an interactive, engaging format. We encourage you to dig into the reading and math Focus Skills for your state, and to see the distribution of Focus Skills across grade levels. Equipped with this knowledge, you can reasonably infer the grade levels with the greatest potential for student learning loss, as determined by the number of Focus Skills. You can also use these lists to identify the most critical building blocks of learning at each grade level, so you know where to focus your efforts for the greatest return in student growth.

We began this blog with the story of a first-year teacher who helped her students close gaps in learning by focusing on what matters the most. Now that you know the power of Focus Skills and how to access them both in Star Assessments and online, we hope you see why these skills will be so critical in the new school year—and the key role they can play in helping students make up lost ground resulting from this spring’s unexpected school closures.

In the next blog in this series, we’ll continue this discussion by focusing on the concept of student mastery—and why mastery is a thoroughly achievable goal in the 2020–2021 school year. To read this blog, click here.

References

Fogarty, R., Kerns, G., & Pete, B. (2017). Unlocking student talent: The new science of developing expertise. New York: Teachers College Press.

Heritage, M. (2017). Personal communication.

Kirkup, C., et al. (2014). Developing National Curriculum-based learning progressions: Reading. Slough: National Foundation for Educational Research. Retrieved from: http://www.renlearn.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/developing-national-curriculum-based-learning-progressions-in-reading.pdf

Lemov, D., Woolway, E., & Yezzi, K. (2012). Practice perfect: 42 rules for getting better at getting better. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mosher, R. (2011). The role of learning progressions in standards-based education reform. CPRE Policy Briefs. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/cpre_policybriefs/40

Sood, A. (2013). The Mayo Clinic guide to stress-free living. Boston: Da Capo Press.

Ready for more insights on using Renaissance Focus Skills to close gaps in student learning? Watch our on-demand webinar presented by Dr. Gene Kerns and Dr. Katie McClarty.