May 1, 2018

All educational assessments, from lengthy high-stakes summative exams to quick skill checks, share one thing in common: They provide a measure of student learning—knowledge, skill, attitude, and/or ability—at a specific moment in time.

When you string together the results of multiple test administrations, you can sometimes zoom out and get a slightly bigger picture: You can see where the student is now, understand where they have been in the past, and perhaps even get a sneak peek of where they may go in the future.

But how do you get the full picture? Not just where students are predicted to go, but what their ultimate destination looks like and how they can get there? Furthermore, how do you make that assessment data actionable so you can use it to help students move forward?

The answer is a learning progression.

A learning progression is the critical bridge that connects assessment, instruction, practice, and academic standards. However, while the right learning progression can help educators and students find a clear path to success, the wrong learning progression may lead them astray and make it that much harder for them to achieve their goals.

In this post, we’ll examine what a learning progression is, how it can be used, and why it’s so important to find a learning progression that truly fits your specific needs.

What are learning progressions?

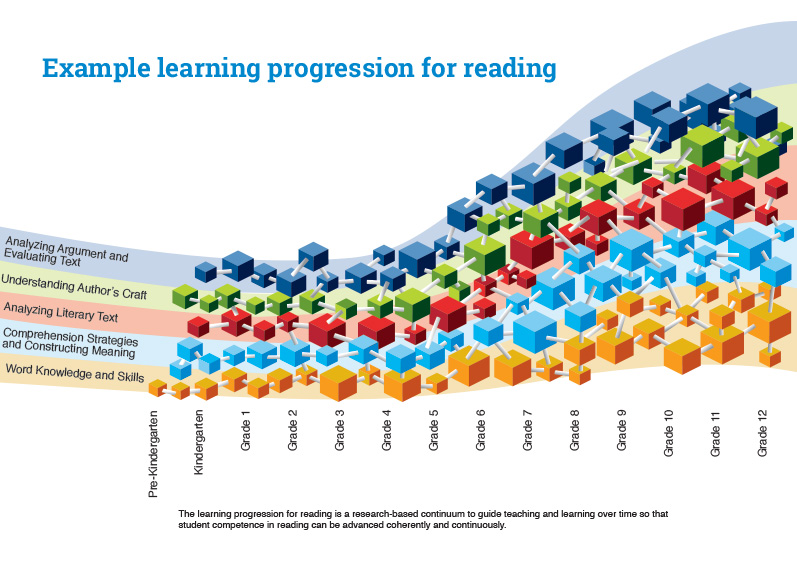

Learning progressions are essentially roadmaps for the learning journey. If academic standards represent waypoints or landmarks along a student’s learning journey (what is learned), with college and career readiness being the ultimate destination, then learning progressions describe possible paths the student might take to get from one location to another (how learning progresses).

Dr. Karin Hess, an internationally recognized educational researcher, described learning progressions as “research‐based, descriptive continuums of how students develop and demonstrate deeper, broader, and more sophisticated understanding over time. A learning progression can visually and verbally articulate a hypothesis about how learning will typically move toward increased understanding for most students.”

“A learning progression can visually and verbally articulate a hypothesis about how learning will typically move toward increased understanding for most students.” — Karin Hess

In simplified terms, learning progressions provide a teachable order of skills. They differ from scopes and sequences in that learning progressions are networks of ideas and practices that reflect the interconnected nature of learning. Learning progressions incorporate both the vertical alignment of skills within a domain and the horizontal alignment of skills across multiple domains. For example, learning progressions recognize that the prerequisites for a specific skill may be in a different domain entirely. A learning progression may also show that skills that at first appear unrelated are often learned concurrently.

Learning progressions can come in all shapes and sizes; they could describe only the steps from one standard to another, or they could encompass the entirety of a child’s pre-K–12 education.

It is critically important to note that there is no one “universal” or “best” learning progression. Think of it this way: With mapping software, there are often multiple routes between two points. The same is true with learning; even the best learning progression will represent only one of many possible routes a student could take. Good learning progressions will describe a “commonly traveled” path that generally works for most students. Great learning progressions will put the educator in the driver’s seat and allow her to make informed course adjustments as needed.

How do I use a learning progression?

To get the most out of a learning progression, an educator must first understand how learning progressions relate to assessment and instruction.

Returning to our roadmap metaphor, academic standards describe the places students must go. Learning progressions identify possible paths students are likely to travel. Instruction is the fuel that moves students along those paths. And assessment is the GPS locator—it tells educators exactly where students are at a specific moment in time.

(Great assessments will also show how fast those students are progressing, if they’re moving at comparable speeds to their peers, and whether they’re accelerating or decelerating—and may even predict where they’ll be at a future time and if they’re on track to reach their learning goals.)

When an assessment is linked with a learning progression, a student’s score places them within the learning progression. While the assessment can identify which skills a student has learned or even mastered, the learning progression can provide the educator insights into which skills a student is likely ready to learn. It answers the question, “What’s next?”

In this way, learning progressions provide a way for assessments to do more than just report on learning that has occurred so far. As Margaret Heritage and Frederic Mosher have stated, “if assessments are seen as standing outside regular instruction, no matter how substantively informative and educative they are … they are very unlikely to be incorporated into and have a beneficial effect on teaching.” Learning progressions are how assessments get “inside” instruction. The combination of the two allows assessments to meaningfully inform instruction.

Educators can use learning progressions to plan or modify instruction to make sure that students are getting the right instruction and content at the right time. If an educator knows she needs to teach a specific skill, she can use the learning progression to look backward and see what prerequisites are needed for that skill. She may also seek out other skills that can be taught alongside her selected skill for more efficient and interconnected teaching, avoiding the repetitious learning than can occur when individual skills are taught in isolation.

For a student who is lagging far behind peers and needs to catch up quickly, a learning progression can identify which skills are the “building blocks” that students need not just for success in their current grade but to succeed in future grades as well (for example, a student will struggle to progress in math if they cannot multiply by 5, but not knowing how to count in a base-5 or quinary numeral system is likely to be less of a roadblock). As a result, the teacher can better concentrate her time and instruction on these focus skills to help the student reach grade level more quickly.

Well-designed learning progressions are often paired with useful resources, such as detailed descriptions or examples of each skill, approaches to teaching the skill for students with different learning needs (such as English Language Learners), information about how the skill relates to domain-level expectations and state standards, and even instructional materials to help teach the skill as well as activities that give students practice with the skill.

Having assessments and resources linked directly to skills within the larger context of the learning progression is ideal for personalized learning, as it allows for educators to quickly see where students are in relation to one another and to the larger learning goals, determine the next best steps to move each student’s learning forward, and find tailored resources that match a student’s specific skill level and learning needs—and ensure that all students are consistently moving toward the same set of grade-level goals, even if they are on different paths.

However, not all learning progressions are well designed—and even an exceptionally well-designed learning progression may lead you and your students astray if it’s not designed to meet your specific needs and goals.

How do I find the right learning progression?

The key is finding a learning progression that’s not just well designed—it should also be designed in a way that matches how you will implement and use it with students.

So what should you look for in a learning progression?

First, it’s very unlikely that you will be selecting a learning progression as a stand-alone resource. Moreover, your learning progression should be tightly linked to your assessment—otherwise you will have no reliable way to place your students in the learning progression. This means that evaluating learning progressions should be a nonnegotiable part of your overall assessment selection process.

(What about assessments without a learning progression? Remember that learning progressions are how assessment data gets “inside” instruction; without a learning progression, it is difficult for assessment to meaningfully inform instruction. Outside of summative assessments—designed to report on past learning rather than guide future instruction—we cannot recommend investing in assessments that are not linked to high-quality learning progressions.)

With that in mind, look for a high-quality learning progression that is:

- Based on research about how students learn and what they need to learn to be ready for the challenges of college, career, and citizenship

- Built and reviewed by educational researchers and subject matter experts, with guidance and advice from independent consultants and content specialists

- Empirically validated using real-world student data to make sure the learning progression reflects students’ actual (observed) order of skill development and that assessment scores are appropriately mapped to the learning progression

- Continually updated based on new research, changes in academic standards, ongoing data collection and validation efforts, and observations from experts in the field

However, even the highest-quality learning progression in the world may be a poor choice if it’s not actually a good fit for your specific needs. In the United States, one of the biggest and most important factors impacting fit is state standards.

Just as there is frequently more than one route to a single destination, there are many skills that can be taught and learned in different, equally logical orders. Different states often choose different orders for the same skills, some add skills that others remove, and many call the same skill by different names. Each learning progression presents one possible order or “roadmap” of learning—but that doesn’t mean it’s the only order out there or that it necessarily matches the order found in your state’s standards.

“There is no single, universally accepted and absolutely correct learning progression.” — W. James Popham

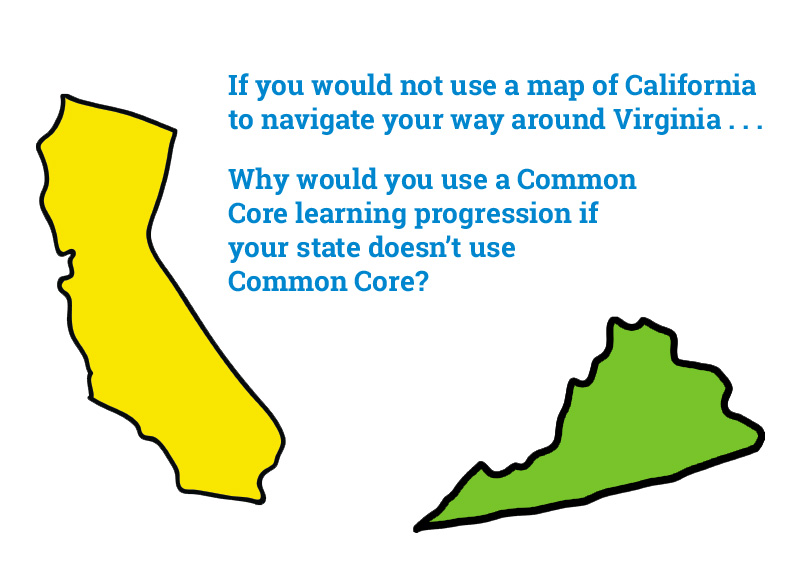

Using a learning progression that is built for another state can be a bit like trying to navigate your way around one state using a map of a completely different state. You may find it quite difficult to reach your destination in time!

Imagine if a teacher in Virginia, whose students must meet the Virginia Standards of Learning, tries to rely on a learning progression aligned with California Common Core State Standards. Even if the Common Core learning progression is of exceptionally high quality, it will be a poor fit for her needs. For example, Virginian students are expected to be able to describe what a median is and to calculate it for any given number set by the end of fifth grade. In Common Core states, that skill is part of the sixth-grade standards.

If our Virginia teacher follows the Common Core learning progression, she will fail to teach her kids a key aspect of her state’s standards and leave them unprepared for their high-stakes math test at the end of the school year. Alternately, she could compare the Common Core learning progression to the Virginia standards and try to keep track of all the ways the two differ—but that’s a lot of extra work for a teacher who already has to squeeze so much into each school day.

If she had a learning progression that already matched the order of the Virginia Standards of Learning, our Virginia teacher could use the learning progression to help all of her students meet all of the state’s standards, in the right order and in the right grade for Virginia.

Your learning progression should be a helpful tool that suggests a logical, easy-to-follow route to success with your state standards. It should not be an obstacle course that forces you to constantly zig and zag between another state’s requirements and your own state’s standards.

Taking things one step further, your learning progression should support a flexible approach to learning. After all, you know your students better than any learning progression ever will. The learning progression doesn’t teach students. It won’t monitor their work to see if they understood the concept taught yesterday. It can’t decide what is a realistic goal for a student. Only you can do that. But your learning progression should make doing all of that easier.

“It is what the teachers actually do in the classroom that is ultimately responsible for ‘learning’ in our schools.” — Mark Wilson

Look for learning progressions that you can interact with—you should be able to look forward and backward within the learning progression to understand how skills can develop. You will want to be able to search for specific skills or standards across the entire learning progression and then find related resources. Your learning progression should also allow you to bundle skills together for instructional purposes, or ungroup any skills to teach discretely if need be. After all, the learning progression is only the roadmap—you’re the one actually driving the car.

How do I find my best assessment?

There are a lot of factors that go into assessment selection—and those factors may differ depending on your school’s or district’s specific needs, goals, and initiatives. However, there are a few universal elements to consider.

As we explored in our last post, you should consider the format of the assessment and the items within it. Are they the best option for the content you’re trying to measure? How quickly will you get results? Think about the reliability, validity, and return on investment. Does the assessment meet your reliability goals? Are you sacrificing a lot of instructional time for a little bit of extra reliability? Consider whether the assessment is appropriate for all your students. Will it work as well for your low-achieving and high-performing students as it does for your on-level students? Can you use it to measure progress over time, including over multiple school years?

Examine the learning progression as well. Does the assessment map to a learning progression? Is it a well-designed learning progression? Is the learning progression aligned to your specific state standards? Does it include additional resources to support instruction and practice? Can you easily interact with and navigate through the learning progression?

Once you’ve selected your best assessment and are ready to use it, you may encounter a different set of questions: When do I assess my students? How often? Why? In our last post in this series, we look at recommendations about assessment timing and frequency from the experts.

Sources

Blythe, D. (2015). Your state, your standards, your learning progression. Renaissance Blog. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Renaissance Learning. Retrieved from https://www.renaissance.com/2015/06/11/your-state-your-standards-your-learning-progression/

California Department of Education. (2014). California Common Core State Standards: Mathematics. Sacramento, CA: Author.

Hess, K. K. (2012). Learning progressions in K‐8 classrooms: How progress maps can influence classroom practice and perceptions and help teachers make more informed instructional decisions in support of struggling learners (Synthesis Report 87). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. Retrieved from http://www.cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/Synthesis87/SynthesisReport87.pdf

Kerns, G. (2014). Learning progressions: Deeper and more enduring than any set of standards. Renaissance Blog. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Renaissance Learning. Retrieved from https://www.renaissance.com/2014/10/02/learning-progressions-deeper-and-more-enduring-than-any-set-of-standards/

Mosher, F., & Heritage, M. (2017). A hitchhiker’s guide to thinking about literacy, learning progressions, and instruction (CPRE Research Report #RR 2017–2). Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education.

National Research Council (NRC). (2007). Taking science to school: Learning and teaching science in grades K–8. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.17226/11625.

Popham, W. J. (2007). All about accountability / The lowdown on learning progressions. Educational Leadership, 64(7), 83-84. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/apr07/vol64/num07/The-Lowdown-on-Learning-Progressions.aspx

Renaissance Learning. (2013). Core Progress for math: Empirically validated learning progressions. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.

Renaissance Learning. (2013). Core Progress for reading: Empirically validated learning progressions. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.

Renaissance Learning. (2013). The research foundation for Star Assessments: The science of star. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.

Virginia Department of Education. (2016). Mathematics Standards of Learning for Virginia public schools. Richmond, VA: Author.

Wilson, M. (2018). Classroom assessment: Continuing the discussion. Educational Measurement, 37(1), 49-51.

Wilson, M. (2018). Making measurement important for education: The crucial role of classroom assessment. Educational Measurement, 37(1), 5-20.

Yettick, H. (2015, November 9). Learning progressions: Maps to personalized teaching. Education Week. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2015/11/11/learning-progressions-maps-to-personalized-teaching.html