June 1, 2017

A familiar definition

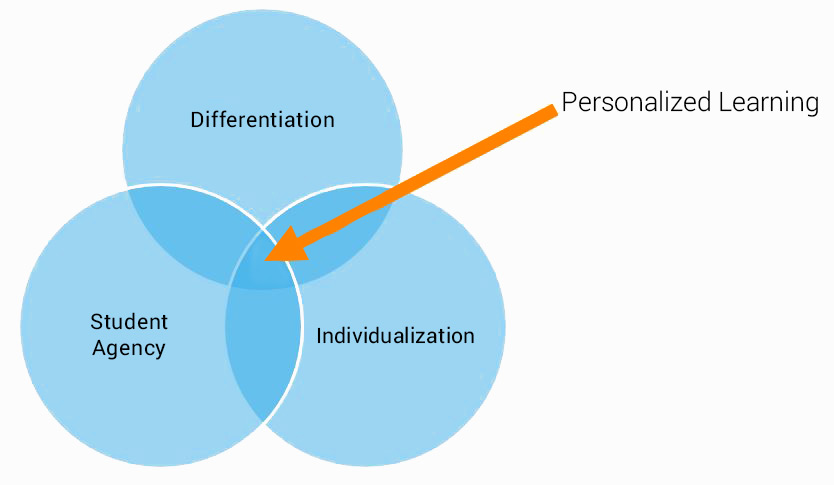

In previous blog posts, I have advanced the U.S. Department of Education’s definition of personalized learning, which asserts that the approach is made up of the following three elements:

- Differentiation

- Individualization (which involves competency or mastery-based learning)

- Student agency

Exploring student agency

Differentiation has been an area of ongoing focus for many, and we previously explored individualization, so our attention now turns to student agency. Renaissance’s EdWords™ offers the following definition:

Student agency refers to learning through activities that are meaningful and relevant to learners, driven by their interests, and often self-initiated with appropriate guidance from teachers. To put it simply, student agency gives students voice and often, choice, in how they learn.

While student agency is a relatively new term within our professional discussions, does this mean that we have never sought to make students agents of their own learning? Certainly not! To varying degrees, teachers have often sought to give students voice and choice within their learning. However, when many other dynamics of the educational setting were fixed (e.g. required pace of learning), only so much choice was possible.

So how do we begin making students agents of their own learning in meaningful ways? I have seen numerous articles in which teachers are discussing this and developing their own strategies from scratch. Is this the best approach?

True empowerment

A common mistake in school improvement is to view a newly framed construct, like student agency, as something that never existed before. While the term “student agency” is relatively new, the concept is not, and well-documented and highly effective strategies already exist, if you know where to look.

I contend that elements of student agency exist within the field of formative assessment, particularly in the work of Dr. Rick Stiggins and his colleagues at the Assessment Training Institute. While numerous authors and researchers have suggested specific strategies for formative classroom assessment, Stiggins and his colleagues have had a unique focus on the impacts of assessment on students, noting formative assessment’s potential to provide feedback that motivates students.

Stiggins (2014) notes effective engagement through assessment as critical because “powerful roadblocks to learning can arise from the very process of assessing and evaluating depending on how the learner interprets what is happening to him or her” (Stiggins, 2014). “Traditional testing practices in the United States … cause many students to give up in hopelessness and accept failure rather than driving them enthusiastically toward academic success” (Stiggins, 2014).

As Fogarty and Kerns (2009) note, “empowering students with understanding and insight about their ability to learn and to retain and to apply is … true empowerment [that] dictates the skillful and robust use of formative assessments as part and parcel of the teaching/learning equation.” This empowerment is synonymous with agency.

Wiliam (2011) advances student agency under the heading of “activating students as owners of their own learning,” and his book Embedded Formative Assessment contains strategies. Elements supporting student agency can also be found in the discussions of metacognitive strategies, goal-setting, self-regulated learning, and having students track their own progress.

In all of this, there is excellent news! First, we don’t have to create all new strategies for student agency. Second, these highlighted areas that advance agency (e.g. formative assessment, metacognition) have been thoroughly researched and proved to have strong positive impacts on student performance (Black and Wiliam, 1998; Hattie, 2009; Stiggins, 2014).

As Stiggins (2014) notes, “Our aspiration must be to give each student a strong sense of control over her or his own academic well-being.” This becomes powerfully motivating and is true agency. It can be accomplished in many ways.

References

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139–148.

Fogarty, R., & Kerns, G. (2009). inFormative assessment: When it’s not about a grade. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Stiggins, R., Arter, J., Chappius, J., & Chappuis, S. (2004). Classroom assessment for student learning: Doing it right – using it well. Portland, OR: Assessment Training Institute.

Stiggins, R. J. (2014). Revolutionize assessment: Empower students, inspire learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.