April 2, 2015

In this post, we take a closer look at validity. In the past we’ve noted that test scores can be reliable (consistent) without being valid, which is why validity ultimately takes center stage. We will still define validity as the extent to which a test measures what it’s intended to measure for the proposed interpretations and uses of test scores.

Going beyond the definition, we begin to talk about evidence—a whole lot of evidence—needed to show that scores are valid for the planned uses. What kind of evidence? Well, it depends. But before you run for the hills, let me tell you that the way we plan to use test scores is the important thing. So, our primary goal is to provide validity evidence in support of the planned score uses.

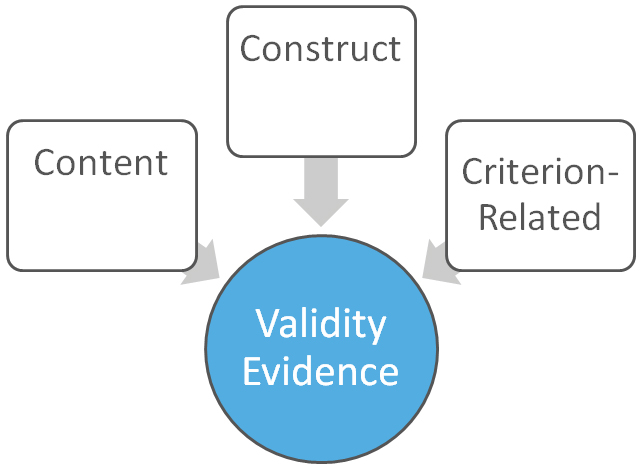

Types of validity evidence

There are several types of validity evidence. Although they are presented separately, they all link back to the construct. A construct is the attribute that we intend to measure. For example, perhaps reading achievement. If the items in a reading achievement test are properly assembled, students’ responses to these items should reflect their reading achievement level. We look for evidence of just that, in various ways.

- Evidence related to construct. Evidence that shows the degree to which a test measures the construct it was intended to measure.

- Evidence related to content. Evidence that shows the extent to which items in a test are adequately matched to the area of interest, say reading.

- Evidence related to a criterion. Evidence that shows the extent to which our test scores are related to a criterion measure. A criterion measure is another measure or test that we desire to compare with our test. There are many types of criterion measures.

Again, these types of evidence all relate to the construct—the attribute the test is intended to measure—as we shall see in the example below. Before we continue, recall that in our last blog on reliability we defined the correlation coefficient statistic. This is another key term to understand when evaluating test validity, because the correlation coefficient is also used to show validity evidence in some instances. When used this way, the correlation coefficient is referred to as a validity coefficient.

An example of a validation process

Suppose we have a test designed to measure reading achievement. The construct here is reading achievement. Can we use the scores from this test to show students’ reading achievement?

First, we might want to look at whether the test is truly measuring reading achievement—our construct. So, we look for construct-related evidence of validity. Evidence commonly takes two forms:

Evidence of a strong relationship between scores from our test and other similar tests that measure reading achievement. If scores from our test and another reading achievement test rank order students in a similar manner, the scores will have a high correlation that we refer to as convergent evidence of validity.

Evidence of a weak relationship between our test and other tests that don’t measure reading achievement. We may find that scores from our test and another test of, say, science knowledge have a low correlation. This low correlation—believe it or not!—is a good thing, and we call it divergent evidence of validity.

Both convergent and divergent evidence are types of construct-related evidence of validity.

Second, a reading achievement test should contain items that specifically measure reading achievement only, as opposed to writing or even math. As a result, we look for content-related evidence of validity. This evidence is contained in what we call a table of specifications or a test blueprint. The test blueprint shows all of the items in a test and the specific knowledge and skill areas that the items assess. Together, all of the items in a test should measure the construct we want to measure. I’ll tell you that although the test blueprint is enough to demonstrate validity evidence related to content, it is only a summary of a much lengthier item development process used to show this type of validity evidence.

Third, being able to compare scores from our test with scores from another similar test that we hold in high esteem is often desirable. This reputable test is an example of a criterion measure. If students take both the reading test and this criterion measure at approximately the same time, we look for a high correlation between the two sets of scores. We refer to this correlation coefficient as concurrent evidence of validity.

What if I told you that you can also predict—without a crystal ball—how your students will likely perform on an end-of-year reading achievement test based on their current scores on our reading test? You may not believe me, but you sure can! You simply take scores on the reading test taken early in the year and compare them with the end-of-year reading test scores for the same students. A high correlation between the two sets of scores tells you that students who score highly on the reading test are also likely to score highly on the end-of-year reading test. This correlation coefficient shows predictive evidence of validity.

Both concurrent and predictive evidence are types of criterion-related evidence of validity.

Finally, there’s a fourth type of validity evidence related to consequences. Validity evidence for consequences of testing refers to both the intended and the unintended consequences of score use. For example, our reading test is designed to measure reading achievement. This is the intended use if we only use it to show how students are performing in reading. However, this same test may also be used for teacher evaluation. This is an unintended score use in this particular instance, because whether the test accurately measures reading achievement—the purpose for which we validated the scores—has no direct relationship with teacher evaluation. If we desire to use the scores for teacher evaluation, we must seek new validity evidence for that specific use.

Still, there are other unintended consequences, usually negative, that don’t call for supporting validity evidence. An example might be an instance where the educator strays from the prescribed curriculum to focus on areas that might give his or her students a chance to score highly on the said reading test and hence deny the students an opportunity to learn important materials.

The burden of proof of validity evidence lies primarily with the test publisher, but a complete list of all unintended uses that may arise from test scores is beyond the realm of possibility. Who then is responsible for validity evidence of unintended score uses not documented by the test publisher? You guessed right—there’s still no agreement on that one.

Test score validity is a deep and complex topic. The above summary is by no means complete, but it gives you a snapshot of the most common types of validity evidence. Again, the specific interpretations we wish to make about test score uses will guide our validation process. Hence, the specific types of validity evidence we look for may be unique to our specific use for the test scores in question.

With validity evidence in hand, how then do you determine whether the evidence is good enough?

Acceptable levels of validity evidence

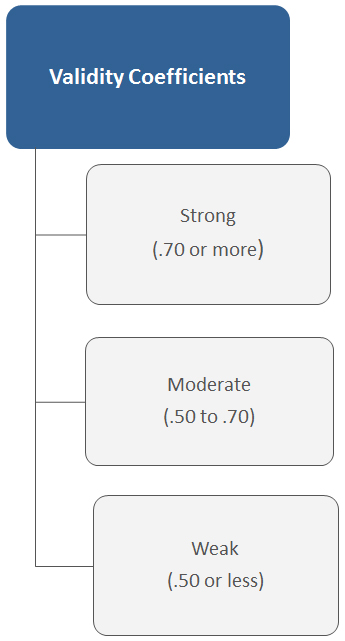

Although validity coefficients generally tend to be smaller than reliability coefficients, validity—much like reliability—is a matter of degree. Just how good is good enough is largely tied to the stakes in decision making. If the stakes are high, stronger evidence might be preferred than if the stakes were lower.

In general, some arbitrary guidelines are cited in literature to help test users interpret validity coefficients. Coefficients equal to .70 or greater are considered strong; coefficients ranging from .50 to .70 are considered moderate, and coefficients less than .50 are considered weak. Usually, there is additional evidence that these coefficients are not simply due to chance.

At Renaissance, we dedicate a whole chapter in the Star technical manuals to document validity as a body of evidence. Part of that evidence shows the validity coefficients, which for the Renaissance Star Assessments range from moderate to strong. To summarize, when judging the validity of test scores, one should consider the available body of evidence. not just the individual coefficients.

The educator’s role in the validation process

For the best outcome, the validation of a test for specific uses is best achieved through collaboration between educators and the test designers. This joint effort ensures that the educator is aware of the intended uses for which the test is designed and seeks new evidence if there’s a need to use scores for purposes not yet validated.

Well, this concludes our series on reliability and validity. I hope this overview of the basics will help you make sense of test scores and better evaluate the assessments available. I hope you’ll also check out my next post on measurement error!

Learn more

To learn more about the power of Renaissance Star Assessments, click the button below.